BIOCHEMISTRY UNIT 2 BSC

UNIT 2 LIPIDS

Introduction to Lipids

Lipids are a diverse group of organic compounds that are insoluble in water but soluble in organic solvents. They play several crucial roles in the human body, ranging from energy storage to forming the structural components of cell membranes and serving as signaling molecules.

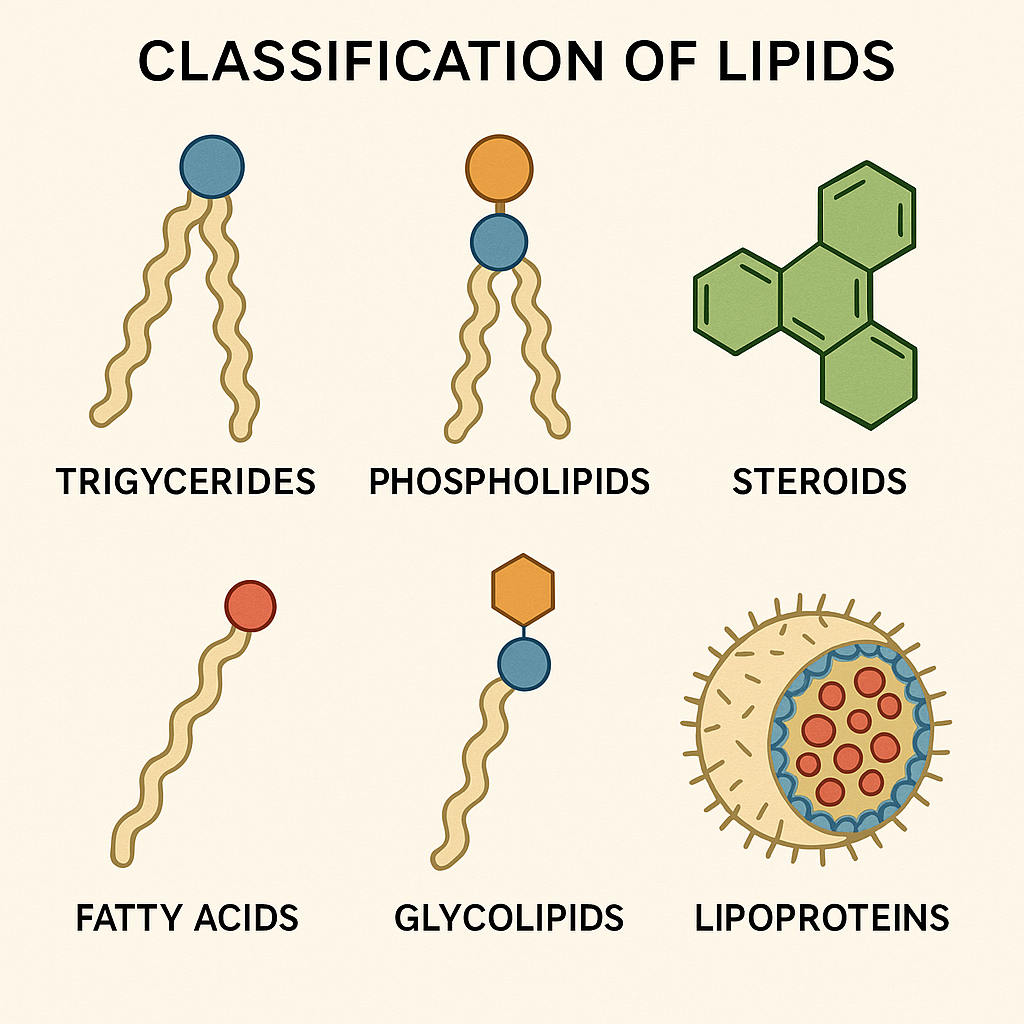

Classification of Lipids

Lipids in the human body are broadly classified into several categories based on their structure and function:

- Triglycerides (Fats and Oils):

- Structure: Triglycerides consist of one molecule of glycerol bound to three fatty acids.

- Function: They are the primary form of stored energy in the body, providing insulation and protection to organs. When metabolized, they produce more energy per gram than carbohydrates or proteins.

- Phospholipids:

- Structure: Composed of glycerol, two fatty acids, and a phosphate group. Phospholipids have hydrophobic (water-repelling) tails and hydrophilic (water-attracting) heads.

- Function: They are the main component of cell membranes, forming a bilayer that separates the internal contents of the cell from its external environment and regulating the passage of substances in and out of the cell.

- Steroids:

- Structure: Steroids have a structure composed of four carbon rings. Cholesterol is the most well-known steroid.

- Function: Cholesterol is a vital component of cell membranes, maintaining their fluidity. It also serves as a precursor for the synthesis of steroid hormones (such as cortisol, estrogen, and testosterone), bile acids, and vitamin D.

- Fatty Acids:

- Structure: Fatty acids are long hydrocarbon chains with a carboxylic acid group at one end. They can be saturated (no double bonds) or unsaturated (one or more double bonds).

- Function: Fatty acids are used as a source of energy, as building blocks for more complex lipids, and as signaling molecules involved in various physiological processes.

- Glycolipids:

- Structure: Glycolipids are lipids with a carbohydrate attached. They are similar to phospholipids but contain sugar molecules instead of the phosphate group.

- Function: Glycolipids are found on the outer surface of cell membranes, where they play a role in cell recognition, communication, and stability of the membrane.

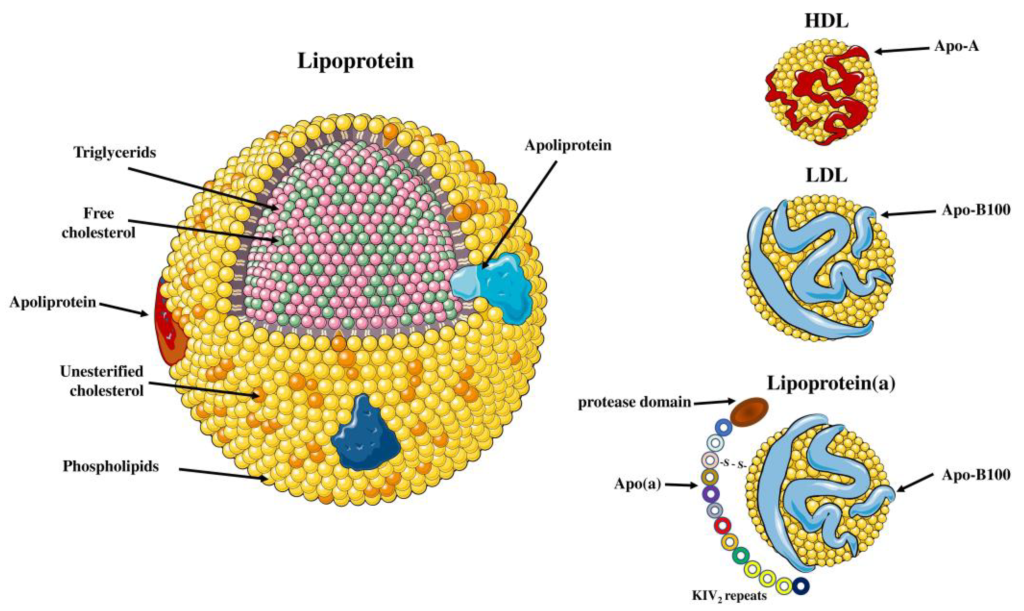

- Lipoproteins:

- Structure: Lipoproteins are complexes of lipids and proteins. They transport lipids, such as triglycerides and cholesterol, through the bloodstream.

- Function: Different types of lipoproteins (e.g., LDL, HDL, VLDL) are involved in the transport and metabolism of lipids, playing key roles in cardiovascular health.

Functions of Lipids in the Human Body

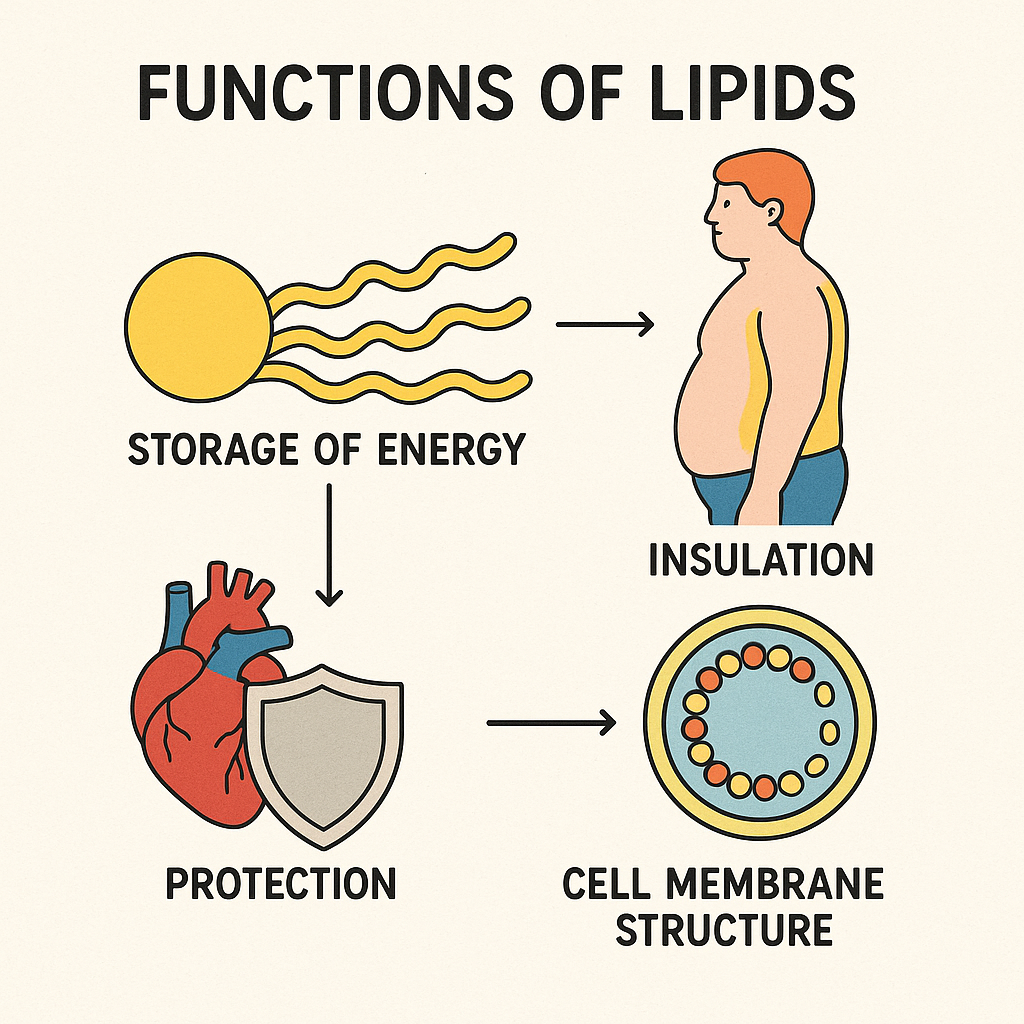

- Energy Storage:

- Lipids, particularly triglycerides, are the most efficient form of energy storage. They provide a dense source of energy that can be mobilized during periods of fasting or increased energy demand.

- Structural Components:

- Lipids are integral components of cell membranes, providing structural integrity and facilitating the formation of barriers between different cellular environments. The amphipathic nature of phospholipids allows them to form bilayers, which are critical to cell function and communication.

- Insulation and Protection:

- Adipose tissue, which is composed of fat cells, provides insulation to maintain body temperature and serves as a cushion to protect vital organs from mechanical injury.

- Hormone Synthesis:

- Cholesterol is a precursor for the synthesis of steroid hormones, which regulate a variety of physiological processes including metabolism, immune function, and reproductive health.

- Cell Signaling:

- Lipids function as signaling molecules that regulate various biological processes. For example, prostaglandins, which are derived from fatty acids, play a role in inflammation and other cellular functions.

- Absorption of Fat-Soluble Vitamins:

- Lipids are necessary for the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K) from the digestive tract into the bloodstream.

- Formation of Bile Acids:

- Cholesterol is used to produce bile acids in the liver, which are essential for the digestion and absorption of dietary fats in the small intestine.

Lipids are essential biomolecules in the human body, performing a wide range of functions that are vital for energy storage, cellular structure, insulation, hormone production, and signaling. Their diverse roles underscore the importance of lipids in maintaining overall health and normal physiological processes. Understanding the various types and functions of lipids helps in appreciating their significance in both health and disease.

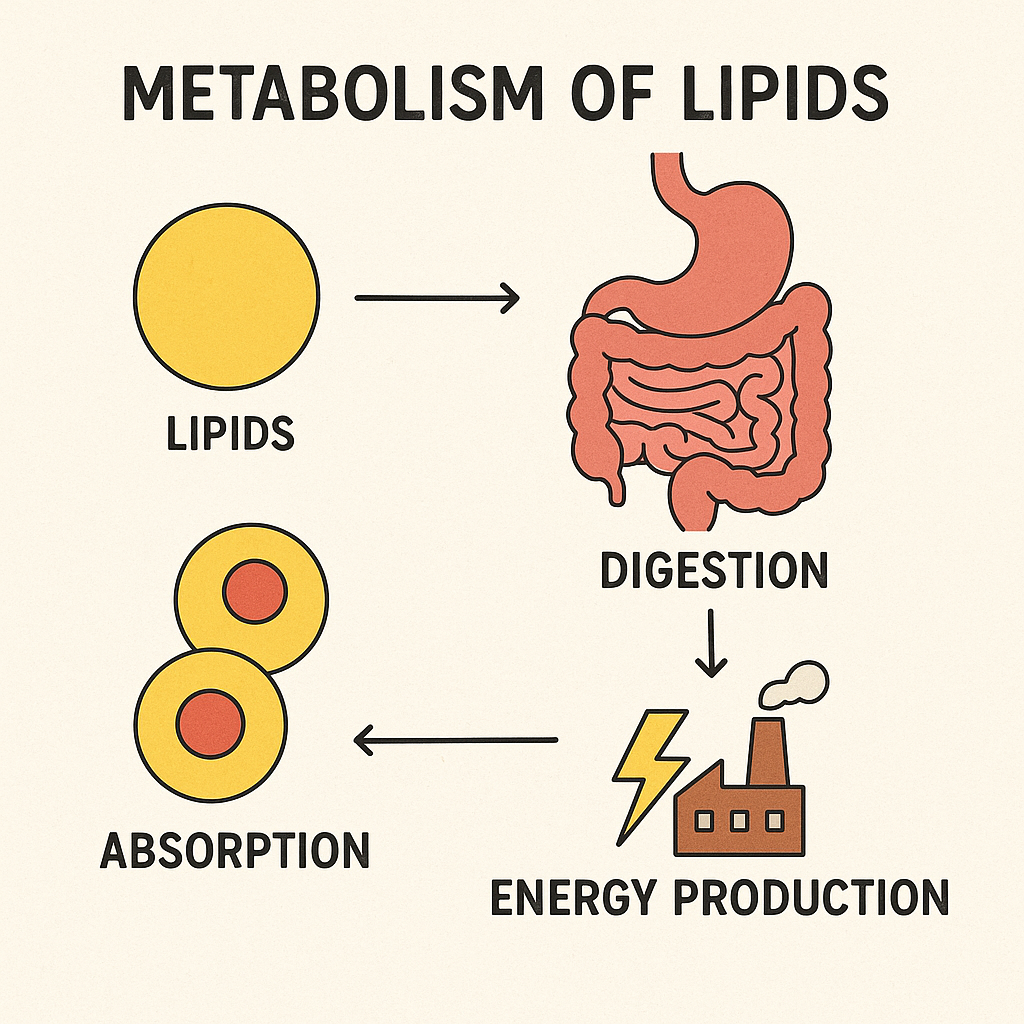

Metabolism of Lipids in the Human Body

Lipid metabolism refers to the processes involved in the synthesis, breakdown, and utilization of lipids in the human body. Lipids, including triglycerides, phospholipids, cholesterol, and fatty acids, are essential for energy production, cellular structure, and signaling. The metabolism of lipids involves several key pathways that ensure these functions are efficiently carried out.

1. Digestion and Absorption of Lipids

- Digestion:

- Lipid digestion begins in the stomach but primarily occurs in the small intestine.

- Bile Salts: Produced by the liver and stored in the gallbladder, bile salts emulsify dietary fats into smaller droplets, increasing their surface area for enzyme action.

- Pancreatic Lipase: Secreted by the pancreas into the small intestine, pancreatic lipase breaks down triglycerides into free fatty acids and monoglycerides.

- Absorption:

- The resulting fatty acids, monoglycerides, and other lipid digestion products are absorbed by the enterocytes (intestinal cells).

- Inside the enterocytes, these products are re-esterified into triglycerides and packaged into chylomicrons (lipoproteins) for transport through the lymphatic system into the bloodstream.

2. Transport of Lipids

- Chylomicrons:

- Chylomicrons transport dietary lipids from the intestines to other tissues in the body. They are released into the lymphatic system and eventually enter the bloodstream.

- In the bloodstream, chylomicrons deliver triglycerides to muscle and adipose tissues for energy production or storage.

- The remnants of chylomicrons are taken up by the liver for further processing.

- Lipoproteins:

- Very-Low-Density Lipoproteins (VLDL): Synthesized in the liver, VLDLs transport endogenous triglycerides and cholesterol to peripheral tissues.

- Low-Density Lipoproteins (LDL): Formed from VLDL remnants, LDLs deliver cholesterol to cells, where it is used for membrane synthesis and hormone production. High levels of LDL are associated with an increased risk of atherosclerosis.

- High-Density Lipoproteins (HDL): HDLs are involved in reverse cholesterol transport, carrying excess cholesterol from tissues back to the liver for excretion. High levels of HDL are protective against cardiovascular disease.

3. Metabolism of Fatty Acids

- Beta-Oxidation:

- Beta-oxidation is the process by which fatty acids are broken down in the mitochondria to generate acetyl-CoA, NADH, and FADH2, which enter the citric acid cycle and the electron transport chain to produce ATP.

- This process occurs primarily in the liver, muscle, and other tissues, providing a significant source of energy, especially during fasting or prolonged exercise.

- Ketogenesis:

- When carbohydrate availability is low, such as during fasting, starvation, or low-carbohydrate diets, the liver converts excess acetyl-CoA from fatty acid oxidation into ketone bodies (acetoacetate, beta-hydroxybutyrate, and acetone).

- Ketone bodies are released into the bloodstream and used as an alternative energy source by the brain, heart, and muscles.

- Fatty Acid Synthesis (Lipogenesis):

- Lipogenesis occurs primarily in the liver and adipose tissue, where excess glucose or amino acids are converted into fatty acids.

- Acetyl-CoA, derived from glucose metabolism, is converted into fatty acids through a series of enzymatic reactions, eventually forming triglycerides, which are stored in adipose tissue.

4. Cholesterol Metabolism

- Cholesterol Synthesis:

- Cholesterol is synthesized primarily in the liver from acetyl-CoA through the mevalonate pathway. This pathway is tightly regulated by the enzyme HMG-CoA reductase.

- Cholesterol is essential for the synthesis of bile acids, steroid hormones (such as cortisol, estrogen, and testosterone), and vitamin D.

- Cholesterol Transport:

- Cholesterol is transported in the blood by lipoproteins, including LDL (which delivers cholesterol to cells) and HDL (which removes excess cholesterol from cells).

- Excretion of Cholesterol:

- Cholesterol is excreted from the body primarily in the form of bile acids, which are synthesized in the liver and secreted into the intestines. Some bile acids are reabsorbed, while the rest are excreted in the feces.

5. Storage of Lipids

- Adipose Tissue:

- Excess lipids are stored as triglycerides in adipose tissue, which serves as the body’s main energy reserve.

- When energy demand increases, stored triglycerides are broken down (lipolysis) into free fatty acids and glycerol, which are released into the bloodstream for use by other tissues.

6. Regulation of Lipid Metabolism

- Insulin:

- Promotes lipid storage by stimulating fatty acid synthesis and inhibiting lipolysis in adipose tissue.

- Enhances the uptake of triglycerides by adipose tissue through the activation of lipoprotein lipase.

- Glucagon and Epinephrine:

- Stimulate lipolysis, leading to the release of fatty acids from adipose tissue during fasting or stress.

- Increase the rate of beta-oxidation in the liver, leading to ketone body production.

- AMP-Activated Protein Kinase (AMPK):

- AMPK is activated during low energy states (e.g., fasting) and inhibits fatty acid synthesis while promoting fatty acid oxidation.

Lipid metabolism is a complex and highly regulated process that ensures the efficient use, storage, and transport of lipids in the human body. It involves the digestion and absorption of dietary fats, the transport of lipids via lipoproteins, the breakdown of fatty acids for energy production, the synthesis of essential molecules like cholesterol, and the storage of excess energy in adipose tissue. Proper regulation of lipid metabolism is critical for maintaining energy balance, cellular function, and overall health. Disruptions in lipid metabolism can lead to metabolic disorders such as obesity, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes.

Fatty Acids: Definition and Classification

Definition of Fatty Acids

Fatty acids are long hydrocarbon chains with a carboxylic acid group (-COOH) at one end. They are a fundamental component of lipids, particularly triglycerides and phospholipids, and play a critical role in various biological processes, including energy production, cell membrane structure, and signaling.

Structure of Fatty Acids

- Hydrocarbon Chain: The length of the hydrocarbon chain varies, typically ranging from 4 to 28 carbon atoms.

- Carboxyl Group: The carboxylic acid group (-COOH) at one end of the molecule is hydrophilic (water-attracting), while the hydrocarbon chain is hydrophobic (water-repelling).

Classification of Fatty Acids

Fatty acids can be classified based on several criteria, including the length of the carbon chain, the presence and number of double bonds, and the configuration of these double bonds.

- Based on Carbon Chain Length

- Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs):

- Definition: Fatty acids with fewer than 6 carbon atoms.

- Examples: Acetic acid (2 carbon atoms), propionic acid (3 carbon atoms), butyric acid (4 carbon atoms).

- Sources: Produced by bacterial fermentation of dietary fiber in the colon.

- Function: SCFAs are important for gut health and serve as an energy source for colonocytes.

- Medium-Chain Fatty Acids (MCFAs):

- Definition: Fatty acids with 6 to 12 carbon atoms.

- Examples: Caproic acid (6 carbon atoms), caprylic acid (8 carbon atoms), capric acid (10 carbon atoms), lauric acid (12 carbon atoms).

- Sources: Found in coconut oil, palm kernel oil, and dairy products.

- Function: MCFAs are absorbed more rapidly than long-chain fatty acids and are quickly metabolized for energy.

- Long-Chain Fatty Acids (LCFAs):

- Definition: Fatty acids with 13 to 21 carbon atoms.

- Examples: Palmitic acid (16 carbon atoms), stearic acid (18 carbon atoms), oleic acid (18 carbon atoms).

- Sources: Common in animal fats, vegetable oils, and nuts.

- Function: LCFAs are a primary source of energy and are stored in adipose tissue as triglycerides.

- Very Long-Chain Fatty Acids (VLCFAs):

- Definition: Fatty acids with 22 or more carbon atoms.

- Examples: Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, 20 carbon atoms), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22 carbon atoms).

- Sources: Found in fish oils and certain plant oils.

- Function: VLCFAs are involved in brain development, cell membrane structure, and anti-inflammatory processes.

- Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs):

- Based on Saturation (Presence of Double Bonds)

- Saturated Fatty Acids (SFAs):

- Definition: Fatty acids with no double bonds between carbon atoms; all carbon atoms are fully saturated with hydrogen atoms.

- Examples: Palmitic acid (16:0), stearic acid (18:0).

- Sources: Commonly found in animal fats, butter, and some tropical oils (e.g., coconut oil, palm oil).

- Function: Saturated fats are solid at room temperature and are used by the body for energy and cell membrane structure.

- Unsaturated Fatty Acids:

- Definition: Fatty acids with one or more double bonds in the hydrocarbon chain.

- Types:

- Monounsaturated Fatty Acids (MUFAs):

- Definition: Fatty acids with one double bond.

- Examples: Oleic acid (18:1, found in olive oil and avocados).

- Function: MUFAs are liquid at room temperature and are associated with cardiovascular health benefits.

- Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFAs):

- Definition: Fatty acids with two or more double bonds.

- Examples: Linoleic acid (18:2, omega-6), alpha-linolenic acid (18:3, omega-3), found in fish oils, flaxseed, and sunflower oil.

- Function: PUFAs are essential fatty acids, meaning they must be obtained from the diet. They play key roles in cell membrane fluidity, inflammatory processes, and brain function.

- Monounsaturated Fatty Acids (MUFAs):

- Saturated Fatty Acids (SFAs):

- Based on the Configuration of Double Bonds

- Cis Fatty Acids:

- Definition: The hydrogen atoms adjacent to the double bond are on the same side of the carbon chain, causing a bend in the molecule.

- Function: Cis configuration is the natural form of unsaturated fatty acids and contributes to the fluidity of cell membranes.

- Trans Fatty Acids:

- Definition: The hydrogen atoms adjacent to the double bond are on opposite sides of the carbon chain, making the molecule more linear.

- Sources: Commonly found in partially hydrogenated oils, such as those used in some margarine and processed foods.

- Health Impact: Trans fats are associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease and are generally considered unhealthy.

- Cis Fatty Acids:

- Based on Essentiality

- Essential Fatty Acids (EFAs):

- Definition: Fatty acids that the body cannot synthesize and must be obtained from the diet.

- Examples: Linoleic acid (omega-6) and alpha-linolenic acid (omega-3).

- Function: EFAs are precursors to important signaling molecules (eicosanoids) and are vital for normal physiological functions, including inflammatory response and cell membrane integrity.

- Non-Essential Fatty Acids:

- Definition: Fatty acids that the body can synthesize from other nutrients.

- Examples: Palmitic acid, oleic acid.

- Function: Non-essential fatty acids are used for energy storage and structural components of cells.

- Essential Fatty Acids (EFAs):

Fatty acids are vital components of lipids with diverse roles in the human body, including energy storage, cell membrane structure, and signaling. Their classification based on chain length, saturation, configuration, and essentiality helps in understanding their functions and implications for health. Essential fatty acids, in particular, are crucial for maintaining normal physiological processes and must be obtained through the diet.

Definition and Clinical Significance of MUFA, PUFA, Essential Fatty Acids, and Trans Fatty Acids

1. Monounsaturated Fatty Acids (MUFA)

- Definition: Monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) are fatty acids that contain one double bond in their hydrocarbon chain. The double bond creates a kink in the molecule, making MUFAs liquid at room temperature but solidify when refrigerated.

- Examples: Oleic acid (18:1) is the most common MUFA, found in olive oil, avocados, nuts, and seeds.

- Clinical Significance:

- Cardiovascular Health: MUFAs are known to reduce low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels, which are associated with a lower risk of heart disease. They may also help increase high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, the “good” cholesterol.

- Anti-inflammatory Effects: MUFAs have been shown to have anti-inflammatory properties, which may reduce the risk of chronic diseases such as atherosclerosis and metabolic syndrome.

- Insulin Sensitivity: Diets high in MUFAs may improve insulin sensitivity, making them beneficial for individuals with type 2 diabetes or those at risk.

2. Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFA)

- Definition: Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) are fatty acids that contain two or more double bonds in their hydrocarbon chain. These double bonds create kinks that prevent tight packing of the molecules, making PUFAs liquid at both room and refrigerated temperatures.

- Types:

- Omega-3 Fatty Acids: Includes alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). Found in fatty fish (such as salmon), flaxseed, walnuts, and chia seeds.

- Omega-6 Fatty Acids: Includes linoleic acid (LA) and arachidonic acid (AA). Found in vegetable oils (such as sunflower, corn, and soybean oils), nuts, and seeds.

- Clinical Significance:

- Cardiovascular Health: Omega-3 PUFAs are particularly beneficial for heart health, as they can lower triglycerides, reduce blood pressure, and decrease the risk of heart attacks and strokes. Omega-6 PUFAs also have cardiovascular benefits when consumed in moderation and as part of a balanced diet.

- Brain Function: DHA, an omega-3 PUFA, is a major component of brain tissue and is crucial for brain development and function. It is particularly important during pregnancy and early childhood.

- Anti-inflammatory and Immune Function: PUFAs are precursors to eicosanoids, which are signaling molecules that regulate inflammation and immune responses. A balance between omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids is important for maintaining optimal inflammatory responses.

- Skin Health: PUFAs play a key role in maintaining skin integrity and function, helping to keep the skin hydrated and protecting against damage.

3. Essential Fatty Acids (EFA)

- Definition: Essential fatty acids (EFA) are fatty acids that cannot be synthesized by the human body and must be obtained from the diet. The two main essential fatty acids are:

- Alpha-linolenic Acid (ALA): An omega-3 fatty acid.

- Linoleic Acid (LA): An omega-6 fatty acid.

- Clinical Significance:

- Cell Membrane Integrity: EFAs are crucial components of cell membranes, contributing to their fluidity and function. They also play a role in the synthesis of signaling molecules.

- Growth and Development: EFAs are essential for normal growth and development, particularly in infants and young children. DHA (derived from ALA) is important for brain and retinal development.

- Inflammation and Immune Response: EFAs are precursors to eicosanoids, which modulate inflammation, blood clotting, and immune function. A proper balance between omega-3 and omega-6 EFAs is important for preventing excessive inflammation.

- Skin Health: Deficiency in EFAs can lead to dry, scaly skin and impaired wound healing.

4. Trans Fatty Acids

- Definition: Trans fatty acids are a type of unsaturated fatty acid where the hydrogen atoms adjacent to the double bond are on opposite sides of the carbon chain, resulting in a more linear structure. This configuration makes trans fats more solid at room temperature, similar to saturated fats.

- Sources:

- Industrial Trans Fats: These are artificially created through a process called partial hydrogenation, which adds hydrogen to liquid vegetable oils to make them more solid. Found in many processed foods, such as margarine, baked goods, and fried foods.

- Natural Trans Fats: Small amounts of trans fats occur naturally in meat and dairy products from ruminant animals (such as cows and sheep).

- Clinical Significance:

- Cardiovascular Disease: Trans fats are strongly associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease. They raise LDL cholesterol levels while lowering HDL cholesterol, contributing to the development of atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries) and increasing the risk of heart attack and stroke.

- Inflammation: Trans fats promote inflammation, which is a key factor in the development of many chronic diseases, including heart disease, diabetes, and cancer.

- Metabolic Health: Diets high in trans fats are linked to insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, and obesity.

- Regulation and Public Health: Due to their adverse health effects, many countries have implemented regulations to reduce or eliminate trans fats from the food supply. The World Health Organization (WHO) has called for the global elimination of industrially produced trans fats by 2023.

Understanding the types and roles of fatty acids in the body is crucial for promoting health and preventing disease. MUFAs and PUFAs, particularly when obtained from natural sources like fish, nuts, and olive oil, are beneficial for heart health, brain function, and inflammation regulation. Essential fatty acids are vital for normal growth, development, and cell function. In contrast, trans fatty acids, particularly those from industrial sources, are harmful to health and should be minimized in the diet to reduce the risk of chronic diseases.

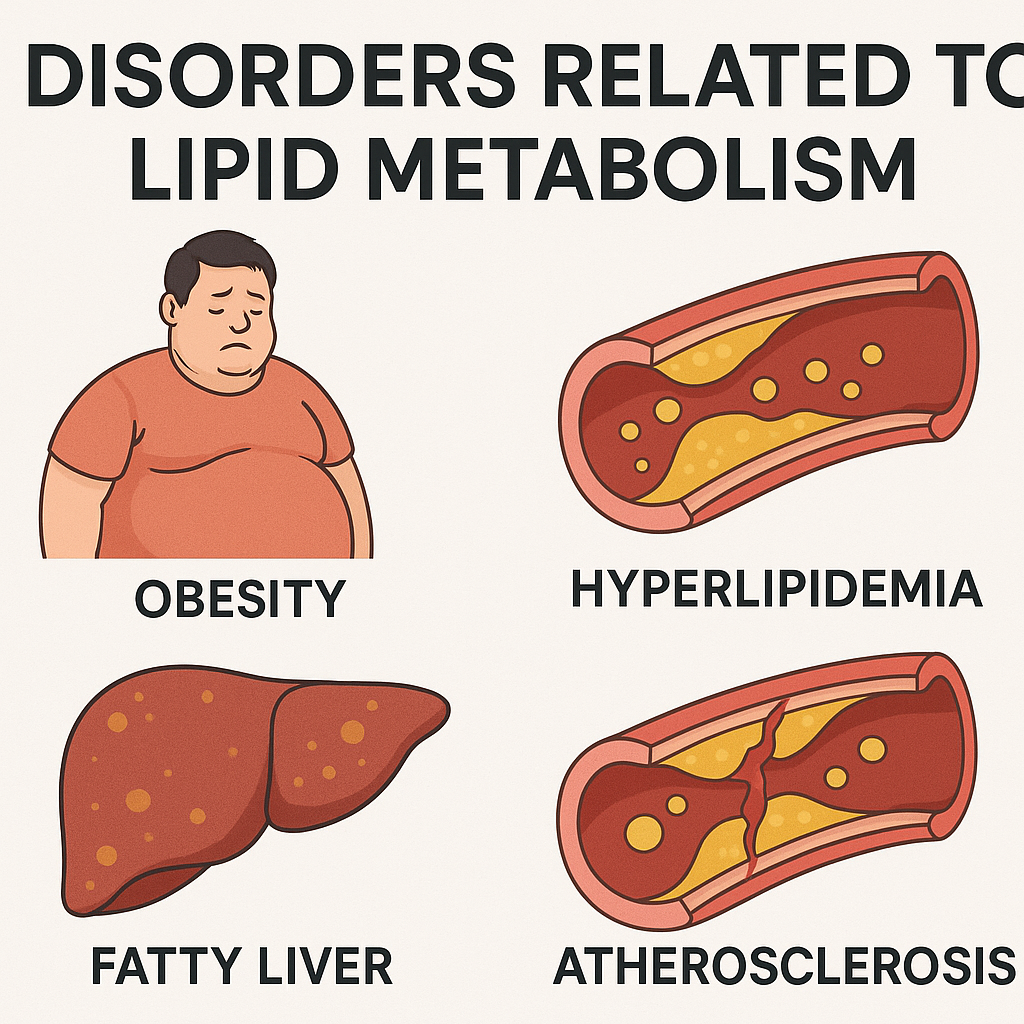

Disorders Related to Lipid Metabolism in the Body

Lipid metabolism disorders are a group of conditions that affect the normal processing of lipids in the body. These disorders can lead to an abnormal accumulation or deficiency of lipids, which can have serious health consequences, including cardiovascular disease, liver dysfunction, and neurological problems. Below are some key disorders related to lipid metabolism:

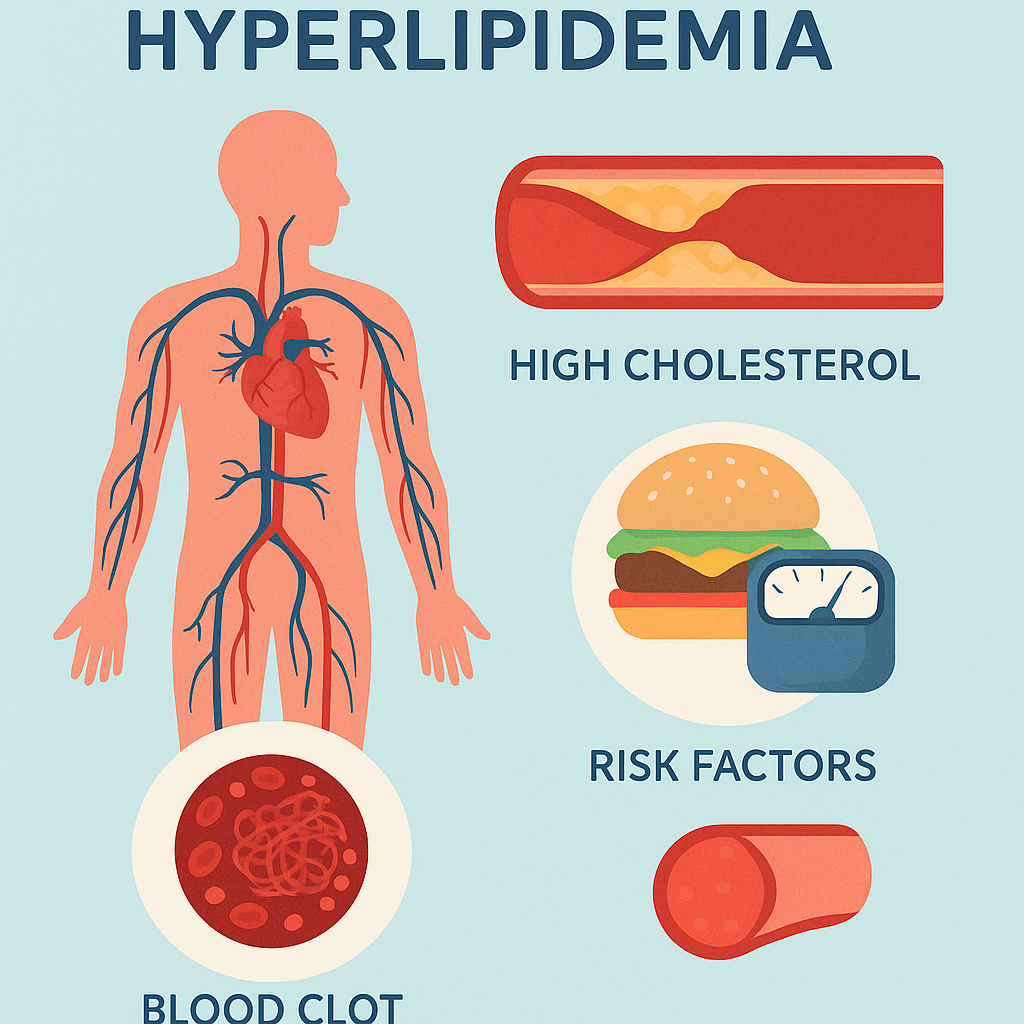

1. Hyperlipidemia

- Definition: Hyperlipidemia refers to elevated levels of lipids (fats) in the blood, including cholesterol and triglycerides. It is one of the most common lipid metabolism disorders.

- Types:

- Hypercholesterolemia: High levels of cholesterol, particularly low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, which is often referred to as “bad cholesterol.”

- Hypertriglyceridemia: Elevated levels of triglycerides in the blood.

- Causes:

- Genetic factors (e.g., familial hypercholesterolemia).

- Poor diet (high in saturated fats and trans fats).

- Sedentary lifestyle.

- Obesity.

- Secondary to other conditions (e.g., diabetes, hypothyroidism).

- Clinical Significance:

- Increased risk of atherosclerosis, leading to cardiovascular diseases such as coronary artery disease, stroke, and peripheral artery disease.

- Pancreatitis in severe cases of hypertriglyceridemia.

- Management:

- Lifestyle modifications (diet and exercise).

- Medications such as statins, fibrates, and omega-3 fatty acids.

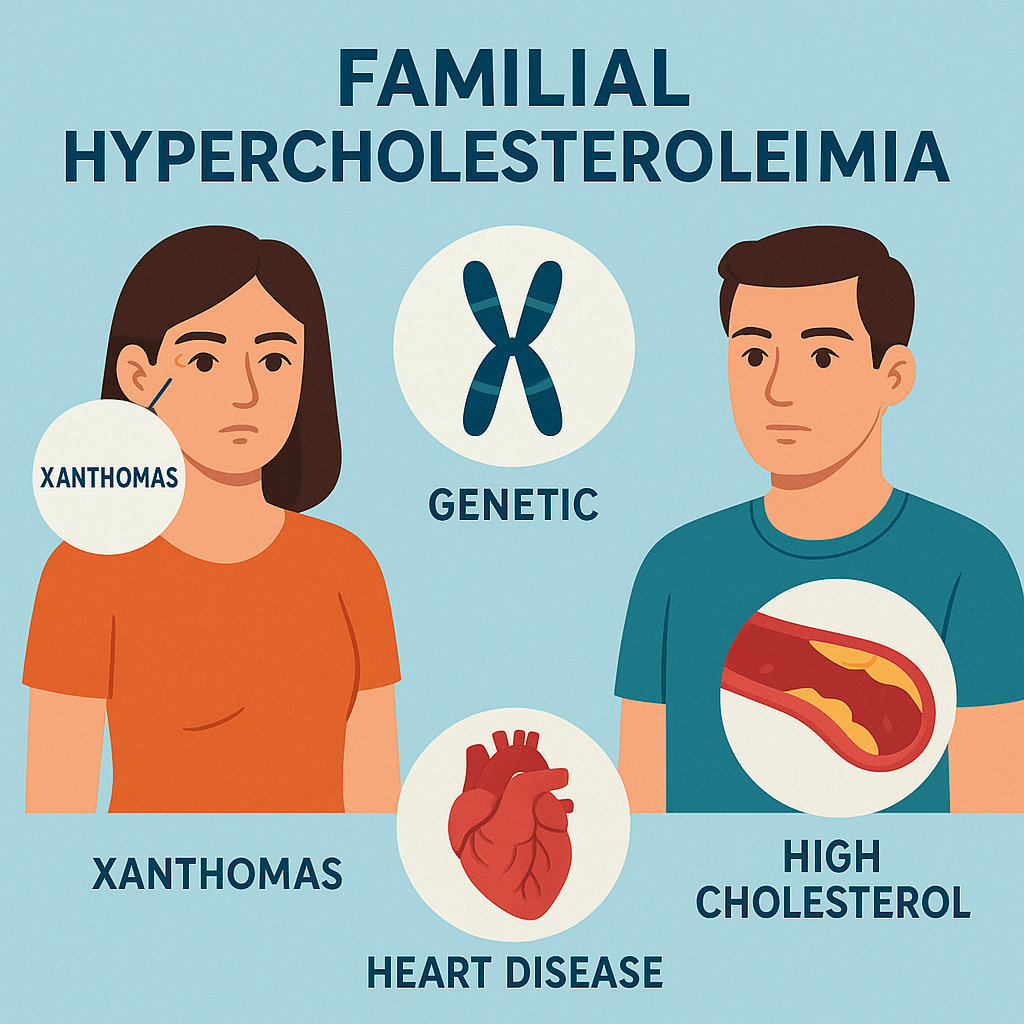

2. Familial Hypercholesterolemia (FH)

- Definition: Familial hypercholesterolemia is a genetic disorder characterized by high levels of LDL cholesterol from birth due to mutations in the LDL receptor gene, which impairs the clearance of LDL from the blood.

- Inheritance:

- Autosomal dominant pattern, meaning a single copy of the mutated gene can cause the disorder.

- Clinical Significance:

- Early development of atherosclerosis, leading to premature cardiovascular disease, often before the age of 50.

- Physical signs such as xanthomas (cholesterol deposits in the skin and tendons) and corneal arcus (cholesterol deposits in the eye).

- Management:

- Aggressive lipid-lowering therapy, including high-dose statins and other lipid-lowering medications.

- Lifestyle modifications.

- In some cases, LDL apheresis (a procedure to remove LDL from the blood).

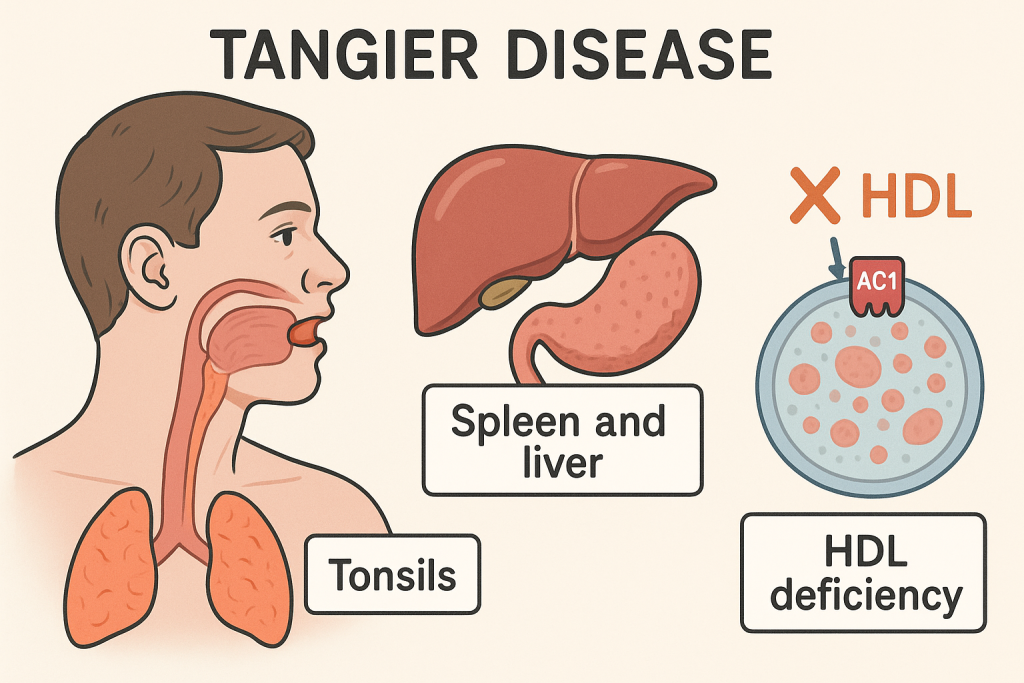

3. Tangier Disease

- Definition: Tangier disease is a rare inherited disorder caused by mutations in the ABCA1 gene, leading to a deficiency in high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, also known as “good cholesterol.”

- Clinical Significance:

- Extremely low or absent HDL cholesterol levels.

- Accumulation of cholesterol in various tissues, leading to enlarged tonsils with a characteristic orange color, hepatosplenomegaly (enlarged liver and spleen), and peripheral neuropathy.

- Increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

- Management:

- There is no specific treatment for Tangier disease. Management focuses on controlling cardiovascular risk factors and symptomatic treatment.

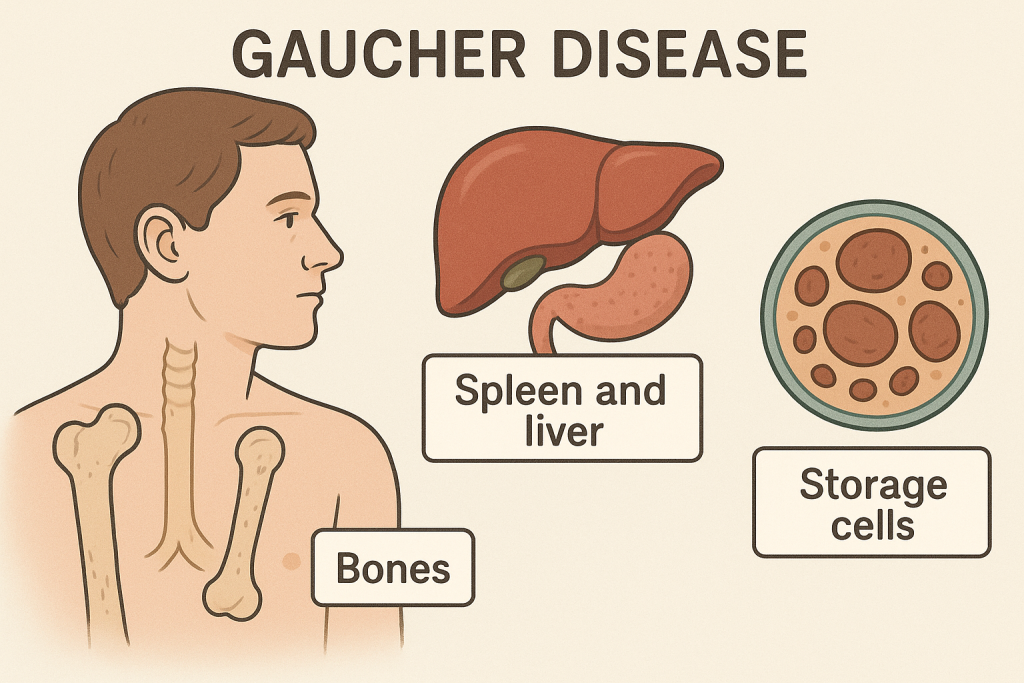

4. Gaucher Disease

- Definition: Gaucher disease is a lysosomal storage disorder caused by a deficiency of the enzyme glucocerebrosidase, leading to the accumulation of glucocerebroside (a glycolipid) in various tissues, particularly in the spleen, liver, and bone marrow.

- Types:

- Type 1: Non-neuropathic form, the most common type, characterized by hepatosplenomegaly, anemia, thrombocytopenia (low platelet count), and bone disease.

- Type 2: Acute neuropathic form, leading to severe neurological impairment in infancy.

- Type 3: Chronic neuropathic form, with milder neurological symptoms than type 2.

- Clinical Significance:

- Organomegaly (enlarged organs), particularly the spleen and liver.

- Bone crises, osteoporosis, and pathological fractures.

- Neurological symptoms in types 2 and 3.

- Management:

- Enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) to replace the deficient enzyme.

- Substrate reduction therapy (SRT) to reduce the accumulation of the lipid.

- Supportive care for symptoms.

5. Niemann-Pick Disease

- Definition: Niemann-Pick disease is a group of inherited lysosomal storage disorders characterized by the accumulation of sphingomyelin (a type of lipid) in various organs due to a deficiency in the enzyme sphingomyelinase or defects in lipid transport.

- Types:

- Type A: Severe infantile form with neurodegenerative symptoms.

- Type B: Milder, non-neuropathic form with primarily visceral involvement (liver, spleen).

- Type C: Caused by a defect in lipid transport, leading to progressive neurological symptoms.

- Clinical Significance:

- Hepatosplenomegaly, pulmonary issues, and neurodegeneration (particularly in types A and C).

- Progressive neurological decline, leading to difficulty with movement, speech, and swallowing.

- Management:

- Supportive care for symptoms.

- Potential therapies being explored include enzyme replacement and substrate reduction therapies, particularly for type C.

6. Hypertriglyceridemia-Induced Pancreatitis

- Definition: Hypertriglyceridemia-induced pancreatitis occurs when extremely high levels of triglycerides lead to inflammation of the pancreas.

- Clinical Significance:

- Symptoms of pancreatitis include severe abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and elevated pancreatic enzymes (amylase and lipase).

- If left untreated, it can lead to severe complications such as necrosis of pancreatic tissue, pseudocyst formation, and systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS).

- Management:

- Immediate lowering of triglyceride levels using medications like fibrates, omega-3 fatty acids, or plasmapheresis in severe cases.

- Intravenous fluids, pain management, and supportive care for pancreatitis.

- Long-term management includes dietary modifications and lipid-lowering therapies to prevent recurrence.

7. Metabolic Syndrome

- Definition: Metabolic syndrome is a cluster of conditions, including central obesity, dyslipidemia (elevated triglycerides and low HDL cholesterol), hypertension, and insulin resistance, which together increase the risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes.

- Clinical Significance:

- Increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes, atherosclerosis, and cardiovascular events such as heart attack and stroke.

- Often associated with fatty liver disease (non-alcoholic fatty liver disease or NAFLD).

- Management:

- Lifestyle interventions focusing on weight loss, increased physical activity, and dietary changes.

- Medications to manage dyslipidemia, hypertension, and insulin resistance.

8. Lipid Storage Myopathies

- Definition: Lipid storage myopathies are a group of inherited metabolic disorders characterized by the abnormal accumulation of lipids in muscle cells, leading to muscle weakness and pain.

- Examples:

- Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase II Deficiency (CPT II Deficiency): Affects fatty acid oxidation, leading to muscle pain, weakness, and myoglobinuria (presence of muscle protein in urine) during exercise or fasting.

- Multiple Acyl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency (MADD): Affects multiple steps in fatty acid oxidation, leading to muscle weakness, hypoglycemia, and metabolic acidosis.

- Clinical Significance:

- Muscle weakness, fatigue, and exercise intolerance.

- Episodes of rhabdomyolysis, where muscle breakdown releases myoglobin into the bloodstream, potentially leading to kidney damage.

- Management:

- Dietary management to avoid fasting and reduce reliance on fatty acid oxidation.

- Supplements like carnitine or riboflavin (vitamin B2) for certain conditions.

- Supportive care and monitoring for complications such as kidney damage.

Disorders related to lipid metabolism can have wide-ranging effects on the body, from cardiovascular and neurological issues to muscle dysfunction and metabolic disturbances. Early diagnosis and management are critical to preventing complications and improving the quality of life for individuals affected by these conditions. Treatment often involves a combination of lifestyle changes, medications, and in some cases, specific therapies targeting the underlying metabolic defect.

Compounds Formed from Cholesterol

Cholesterol is a vital molecule in the human body that serves as a precursor for the synthesis of several important compounds. These compounds play crucial roles in various physiological processes, including the formation of cell membranes, the production of hormones, and the digestion of fats. Here are the primary compounds formed from cholesterol:

1. Steroid Hormones

Cholesterol is the precursor for all steroid hormones, which are synthesized in the adrenal glands, ovaries, and testes. These hormones are involved in a wide range of physiological functions, including metabolism, immune response, reproductive health, and stress response.

- Glucocorticoids:

- Example: Cortisol

- Function: Regulate metabolism, immune response, and stress; increase blood glucose levels.

- Mineralocorticoids:

- Example: Aldosterone

- Function: Regulate sodium and potassium balance, and blood pressure by acting on the kidneys.

- Sex Hormones:

- Androgens (e.g., testosterone):

- Function: Promote the development of male secondary sexual characteristics and reproductive function.

- Estrogens (e.g., estradiol):

- Function: Promote the development of female secondary sexual characteristics, reproductive function, and regulation of the menstrual cycle.

- Progestogens (e.g., progesterone):

- Function: Prepare and maintain the uterus for pregnancy and regulate the menstrual cycle.

- Androgens (e.g., testosterone):

2. Bile Acids and Bile Salts

Cholesterol is converted into bile acids in the liver, which are then conjugated with amino acids (such as glycine or taurine) to form bile salts. Bile salts are crucial for the digestion and absorption of dietary fats.

- Primary Bile Acids:

- Cholic Acid

- Chenodeoxycholic Acid

- Bile Salts:

- Glycocholic Acid

- Taurocholic Acid

- Function:

- Bile salts emulsify fats in the small intestine, breaking them down into smaller droplets that can be more easily digested by pancreatic lipase.

- Facilitate the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) and other lipids.

3. Vitamin D

Cholesterol is the precursor for the synthesis of vitamin D, particularly vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol). This process begins in the skin and involves the action of ultraviolet (UV) light.

- Synthesis:

- 7-Dehydrocholesterol (a derivative of cholesterol) in the skin is converted to vitamin D3 upon exposure to UVB radiation from sunlight.

- Vitamin D3 is then hydroxylated in the liver to form 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 (calcidiol) and further hydroxylated in the kidneys to form the active hormone 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (calcitriol).

- Function:

- Vitamin D is essential for calcium and phosphorus homeostasis, promoting their absorption in the intestines, and maintaining bone health.

- It also plays roles in immune function, inflammation regulation, and cell growth.

4. Cell Membrane Components

Cholesterol is an integral component of cell membranes, contributing to their structure and function.

- Function:

- Cholesterol maintains the fluidity and stability of cell membranes, enabling them to function properly under varying temperature conditions.

- It is involved in the formation of lipid rafts, which are specialized areas of the membrane that play critical roles in cell signaling and trafficking.

5. Cholesteryl Esters

Cholesterol can be esterified with a fatty acid to form cholesteryl esters, which are the storage form of cholesterol in the body.

- Function:

- Cholesteryl esters are transported in the bloodstream within lipoproteins, such as low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and high-density lipoprotein (HDL).

- They are stored in lipid droplets within cells and can be mobilized when cholesterol is needed for membrane synthesis or hormone production.

Cholesterol is a vital molecule that serves as a precursor for a variety of important compounds in the human body. These include steroid hormones (such as cortisol, aldosterone, and sex hormones), bile acids and bile salts, vitamin D, cell membrane components, and cholesteryl esters. Each of these compounds plays a critical role in maintaining physiological functions, from metabolism and digestion to immune response and reproductive health. Despite its association with cardiovascular disease when present in excess, cholesterol is essential for life and is involved in many key biological processes.

Ketone Bodies

Ketone bodies are water-soluble molecules produced by the liver during the breakdown of fatty acids. They serve as an alternative energy source when glucose availability is low, such as during fasting, prolonged exercise, or carbohydrate-restricted diets.

Types of Ketone Bodies:

- Acetoacetate (AcAc)

- Beta-Hydroxybutyrate (BHB)

- Acetone

Significance of Ketone Bodies:

- Energy Source: Ketone bodies are used by various tissues, including the brain, heart, and muscles, as an alternative energy source, especially during periods of low carbohydrate intake or insulin deficiency.

- Ketosis: A metabolic state in which ketone bodies are elevated in the blood and urine, providing energy when glucose is scarce.

- Ketoacidosis: A potentially dangerous condition, particularly in individuals with uncontrolled diabetes (diabetic ketoacidosis), where excessively high levels of ketone bodies cause the blood to become acidic.

- Therapeutic Uses: Ketogenic diets, which promote the production of ketone bodies, are used in the management of certain medical conditions, such as epilepsy and metabolic disorders, and are also popular for weight loss.

Lipoproteins: Types and Functions

Lipoproteins are complexes of lipids and proteins that transport lipids (fats) through the bloodstream. They are essential for the metabolism and transport of cholesterol, triglycerides, and other lipids to various tissues in the body.

Types of Lipoproteins:

- Chylomicrons

- Very Low-Density Lipoproteins (VLDL)

- Intermediate-Density Lipoproteins (IDL)

- Low-Density Lipoproteins (LDL)

- High-Density Lipoproteins (HDL)

Functions of Each Type:

- Chylomicrons

- Function: Chylomicrons are responsible for transporting dietary triglycerides and cholesterol from the intestines to peripheral tissues, such as muscle and adipose tissue, where triglycerides are either used for energy or stored.

- Key Role: After delivering triglycerides, chylomicron remnants are taken up by the liver for processing.

- Very Low-Density Lipoproteins (VLDL)

- Function: VLDLs are produced by the liver and primarily transport endogenous triglycerides (those synthesized by the body) and cholesterol to peripheral tissues.

- Key Role: As VLDLs lose triglycerides to tissues through the action of lipoprotein lipase, they are converted into IDL and eventually LDL.

- Intermediate-Density Lipoproteins (IDL)

- Function: IDLs are transitional lipoproteins that are formed as VLDLs lose triglycerides. They can be further processed by the liver into LDLs or be taken up directly by the liver.

- Key Role: IDLs are an intermediate step in the conversion of VLDLs to LDLs.

- Low-Density Lipoproteins (LDL)

- Function: LDLs are the primary carriers of cholesterol to cells throughout the body. They deliver cholesterol to cells for use in membrane synthesis, hormone production, and other functions.

- Key Role: LDL is often referred to as “bad cholesterol” because high levels can lead to the buildup of cholesterol in the walls of arteries, increasing the risk of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease.

- High-Density Lipoproteins (HDL)

- Function: HDLs are responsible for reverse cholesterol transport, carrying excess cholesterol from peripheral tissues back to the liver for excretion or recycling. This process helps maintain cholesterol balance in the body.

- Key Role: HDL is often referred to as “good cholesterol” because higher levels of HDL are associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease, as they help clear cholesterol from the arteries.

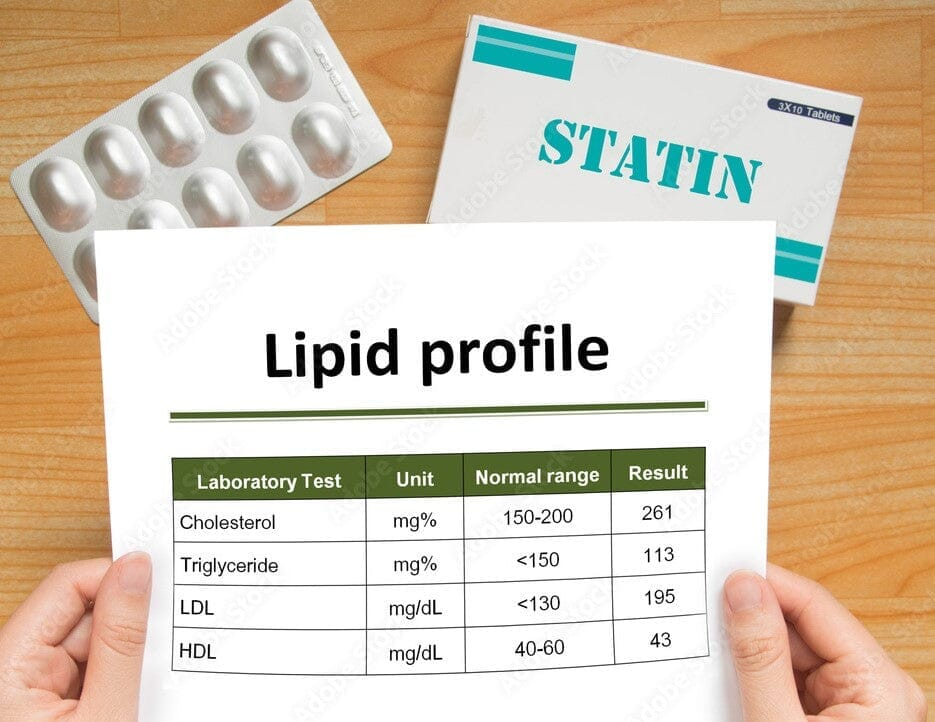

Lipid Profile

A lipid profile (or lipid panel) is a blood test that measures the levels of specific lipids in the bloodstream. It is commonly used to assess an individual’s risk of cardiovascular disease, including heart disease and stroke. The lipid profile provides essential information about the different types of cholesterol and triglycerides in the blood.

Components of a Lipid Profile:

- Total Cholesterol

- Definition: The sum of all cholesterol in the blood, including LDL, HDL, and VLDL.

- Significance: High levels of total cholesterol can indicate an increased risk of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease.

- Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (LDL-C)

- Definition: Often referred to as “bad cholesterol,” LDL carries cholesterol to cells, but high levels can lead to cholesterol buildup in artery walls.

- Significance: Elevated LDL-C levels are strongly associated with an increased risk of coronary artery disease, heart attack, and stroke.

- High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (HDL-C)

- Definition: Known as “good cholesterol,” HDL helps remove excess cholesterol from the bloodstream and transports it to the liver for excretion.

- Significance: Higher levels of HDL-C are associated with a lower risk of heart disease because HDL helps protect against the buildup of cholesterol in the arteries.

- Triglycerides

- Definition: A type of fat found in the blood, triglycerides are the most common form of fat in the body and are stored in fat cells for energy.

- Significance: High levels of triglycerides can increase the risk of heart disease, particularly when associated with low HDL-C or high LDL-C levels.

- Very Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (VLDL-C)

- Definition: VLDL carries triglycerides from the liver to tissues in the body. VLDL-C is often calculated as a part of the lipid profile.

- Significance: Elevated VLDL-C levels are associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, similar to LDL-C.

Typical Lipid Profile Values:

- Total Cholesterol:

- Desirable: Less than 200 mg/dL (5.2 mmol/L)

- Borderline High: 200-239 mg/dL (5.2-6.2 mmol/L)

- High: 240 mg/dL (6.2 mmol/L) and above

- LDL Cholesterol:

- Optimal: Less than 100 mg/dL (2.6 mmol/L)

- Near Optimal/Above Optimal: 100-129 mg/dL (2.6-3.3 mmol/L)

- Borderline High: 130-159 mg/dL (3.4-4.1 mmol/L)

- High: 160-189 mg/dL (4.1-4.9 mmol/L)

- Very High: 190 mg/dL (4.9 mmol/L) and above

- HDL Cholesterol:

- Low (Increased Risk): Less than 40 mg/dL (1.0 mmol/L) for men, Less than 50 mg/dL (1.3 mmol/L) for women

- Desirable: 60 mg/dL (1.6 mmol/L) and above

- Triglycerides:

- Normal: Less than 150 mg/dL (1.7 mmol/L)

- Borderline High: 150-199 mg/dL (1.7-2.2 mmol/L)

- High: 200-499 mg/dL (2.3-5.6 mmol/L)

- Very High: 500 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L) and above

Clinical Significance:

- Cardiovascular Risk Assessment: A lipid profile is a critical tool for evaluating an individual’s risk of developing cardiovascular diseases, including heart attack and stroke. It helps guide decisions regarding lifestyle modifications, dietary changes, and medication (e.g., statins) to manage cholesterol and triglyceride levels.

- Monitoring Treatment: For individuals with known cardiovascular disease or those undergoing treatment for high cholesterol or triglycerides, regular lipid profile testing helps monitor the effectiveness of treatment and ensures that lipid levels are being adequately controlled.

- Other Health Conditions: Abnormal lipid levels can also be associated with other conditions such as metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and pancreatitis (in the case of very high triglycerides).

A lipid profile is an essential diagnostic tool that provides comprehensive information about the levels of cholesterol and triglycerides in the blood. It plays a vital role in assessing cardiovascular risk, guiding treatment decisions, and monitoring the effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing the risk of heart disease and related conditions. Regular testing and interpretation of lipid profiles are crucial components of preventive healthcare.

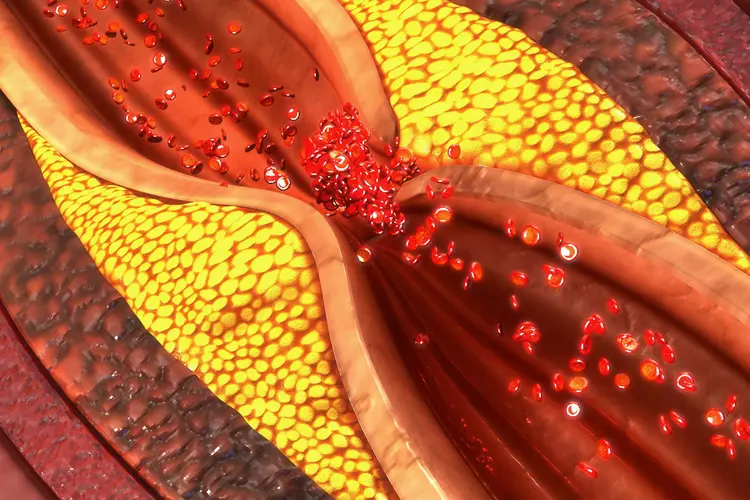

Atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis is a chronic, progressive condition in which the arteries become narrowed and hardened due to the buildup of plaque on their inner walls. This plaque is composed of cholesterol, fatty substances, cellular waste products, calcium, and fibrin (a clotting material in the blood). Atherosclerosis is a key underlying cause of cardiovascular diseases, including coronary artery disease, heart attacks, strokes, and peripheral artery disease.

Pathophysiology:

- Plaque Formation: Atherosclerosis begins with damage to the endothelium, the inner lining of the arteries, often caused by factors such as high blood pressure, smoking, or high cholesterol. This damage allows LDL cholesterol to enter the artery wall, where it is oxidized and taken up by macrophages, forming foam cells. These foam cells accumulate and contribute to the development of fatty streaks, the early stage of plaque formation.

- Plaque Progression: Over time, the fatty streaks grow as more lipids, calcium, and other cellular materials are deposited. The plaque hardens, narrowing the artery and reducing blood flow. The arterial wall may also become stiff, a condition known as arteriosclerosis.

- Complications: Atherosclerotic plaques can rupture, leading to the formation of a blood clot at the site. If the clot significantly blocks the artery or breaks loose and travels to another part of the body, it can cause severe complications, such as a heart attack (if the coronary arteries are affected) or a stroke (if the carotid or cerebral arteries are involved).

Risk Factors:

- High blood cholesterol levels

- Hypertension (high blood pressure)

- Smoking

- Diabetes

- Obesity

- Sedentary lifestyle

- Unhealthy diet, particularly high in saturated fats and trans fats

- Age (risk increases with age)

- Family history of cardiovascular disease

Clinical Significance:

- Coronary Artery Disease (CAD): Atherosclerosis in the coronary arteries can lead to chest pain (angina) and heart attacks.

- Cerebrovascular Disease: Atherosclerosis in the arteries supplying the brain can lead to strokes and transient ischemic attacks (TIAs).

- Peripheral Artery Disease (PAD): Atherosclerosis in the peripheral arteries (especially in the legs) can cause pain, cramping, and, in severe cases, tissue death (gangrene).

Prevention and Management:

- Lifestyle Modifications: Healthy diet (low in saturated fats and trans fats, high in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains), regular physical activity, maintaining a healthy weight, and quitting smoking.

- Medications: Statins (to lower cholesterol), antihypertensives (to control blood pressure), antiplatelet drugs (e.g., aspirin) to reduce clot formation.

- Surgical Interventions: In severe cases, procedures like angioplasty (to open narrowed arteries) or bypass surgery (to create a new pathway for blood flow) may be necessary.

Atherosclerosis is a leading cause of cardiovascular diseases, significantly impacting global health. Early detection and management through lifestyle changes, medications, and, if necessary, surgical interventions are essential to prevent serious complications like heart attacks and strokes.

FOR UNLOCK 🔓 FULL COURSE NOW. MORE DETAILS CALL US OR WATSAPP ON- 8485976407