BSC SEM 1 UNIT 11 APPLIED NUTRITION AND DIETETICS

UNIT 11 Nutrition assessment and nutrition education

Nutrition Assessment and Nutrition Education.

I. Nutrition Assessment

Definition:

Nutrition assessment is the systematic process of collecting, analyzing, and interpreting data to identify an individual’s or a population’s nutritional status, nutritional deficiencies, and related health risks.

Components of Nutrition Assessment (ABCD Approach)

- Anthropometric Measurements

- Measurements of the body to assess growth, development, and health status.

- Common methods:

- Height and Weight – Assesses underweight, overweight, and obesity.

- Body Mass Index (BMI) – Weight (kg) / Height (m²); used for assessing nutritional status.

- Mid-Upper Arm Circumference (MUAC) – Measures muscle and fat stores, especially in children and pregnant women.

- Head Circumference – Used for infants to assess brain growth.

- Waist-to-Hip Ratio (WHR) – Assesses central obesity risk.

- Biochemical Assessment

- Laboratory tests help detect nutritional deficiencies and metabolic disorders.

- Common tests:

- Hemoglobin (Hb) – Assesses iron status (anemia).

- Serum Albumin – Assesses protein status.

- Lipid Profile – Assesses cholesterol and triglycerides for cardiovascular risk.

- Blood Glucose – Evaluates diabetes risk.

- Vitamin and Mineral Levels – Assesses deficiencies (e.g., Vitamin D, B12, Iron, Calcium).

- Clinical Assessment

- Physical examination to identify visible signs of malnutrition and deficiency.

- Common signs:

- Pale skin, fatigue (Iron deficiency anemia).

- Goiter (Iodine deficiency).

- Edema (Protein deficiency – Kwashiorkor).

- Scurvy (Vitamin C deficiency – bleeding gums).

- Night blindness (Vitamin A deficiency).

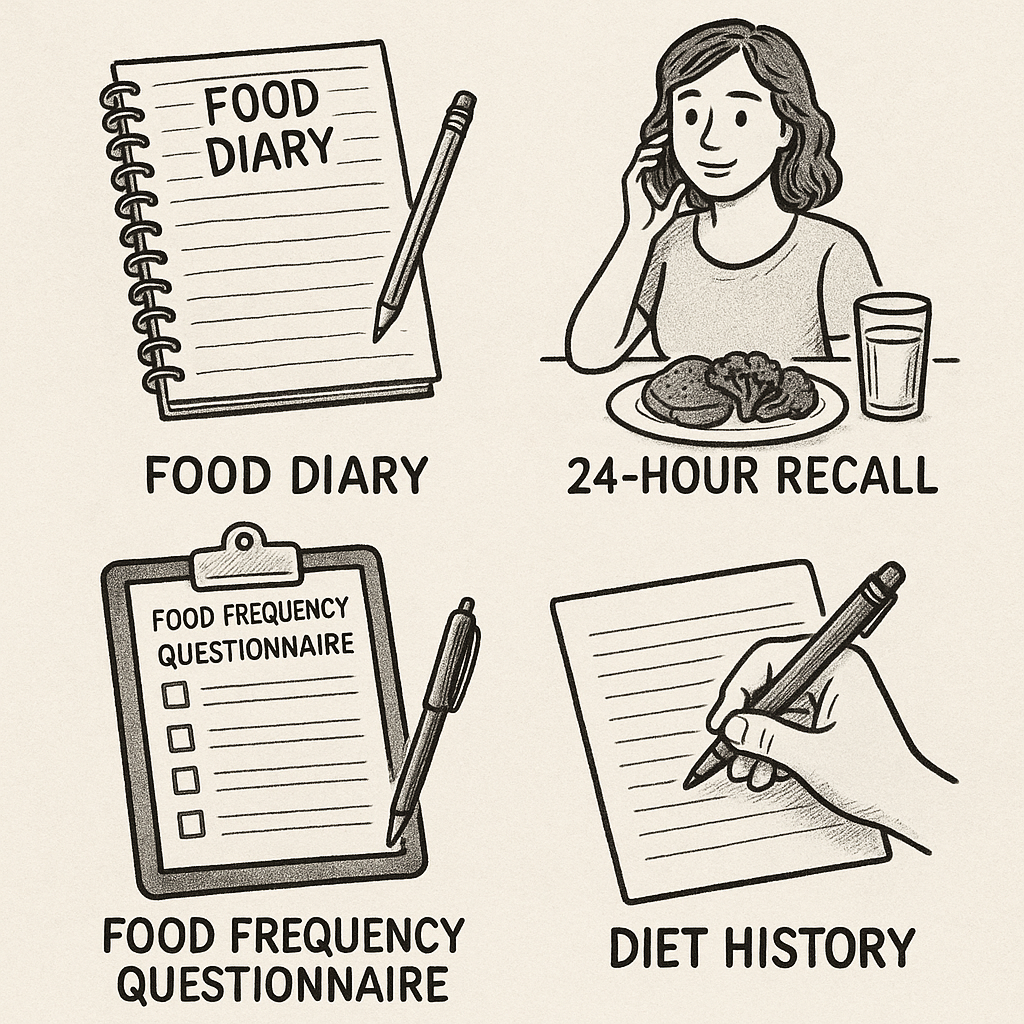

- Dietary Assessment

- Evaluates food intake patterns and eating habits.

- Methods include:

- 24-Hour Dietary Recall – Records all foods consumed in the past 24 hours.

- Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) – Assesses regular dietary patterns.

- Diet History – In-depth interview about food habits, allergies, and meal patterns.

- Food Diary – Individual records food intake over several days.

Methods of Nutrition Assessment

- Individual Level:

- Used for diagnosing malnutrition, obesity, and nutrient deficiencies in individuals.

- Helps in designing personalized diet plans.

- Community Level:

- Used to assess the nutritional status of a population.

- Data from surveys, public health records, and school health programs.

- National/Global Level:

- Large-scale nutrition surveys (e.g., National Family Health Survey – NFHS, WHO Global Nutrition Report).

- Helps in formulating public health policies.

II. Nutrition Education

Definition:

Nutrition education is a process of instructing individuals and communities about healthy eating habits, balanced diets, and the prevention of diet-related diseases.

Objectives of Nutrition Education

- Promote awareness about nutrition-related health risks.

- Encourage healthy food choices to prevent malnutrition, obesity, and chronic diseases.

- Teach meal planning, food safety, and hygiene to improve dietary habits.

- Empower individuals and communities to take responsibility for their health.

- Prevent lifestyle-related diseases like diabetes, heart disease, and hypertension.

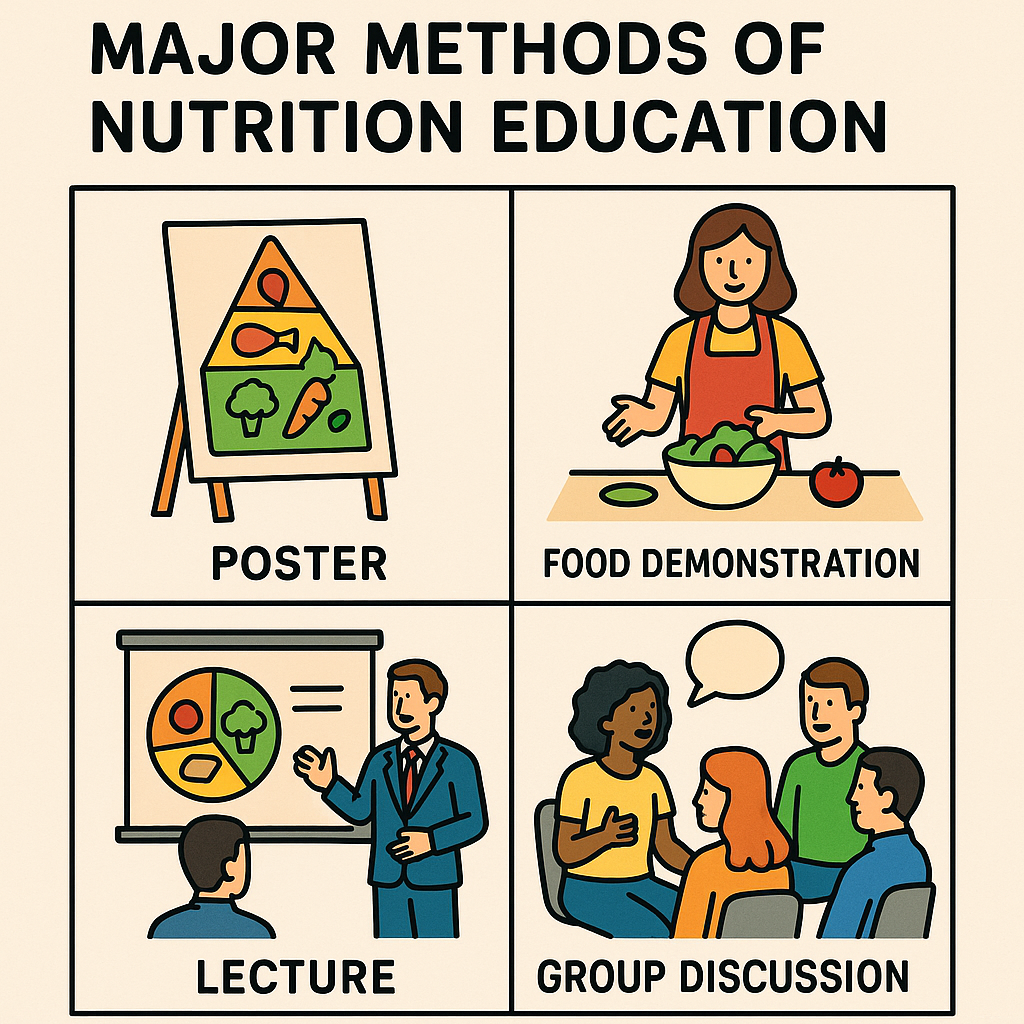

Methods of Nutrition Education

- Individual Counseling:

- One-on-one sessions with a dietitian or health professional.

- Personalized diet plans for specific conditions (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, pregnancy).

- Group Education Programs:

- Community-based workshops, cooking demonstrations, and food safety training.

- Targets specific groups like pregnant women, school children, and elderly individuals.

- Mass Media Campaigns:

- Television, radio, social media, and posters to spread awareness.

- Example: Government campaigns on malnutrition prevention and healthy eating.

- School-Based Nutrition Education:

- Integrating nutrition topics into the school curriculum.

- Teaching students about healthy eating habits from a young age.

- Workplace Nutrition Programs:

- Educating employees about healthy meal options and lifestyle changes.

- Conducting health check-ups and wellness sessions.

- Digital and Mobile Health Education:

- Mobile apps, online courses, and teleconsultations for diet management.

- Use of AI-driven health tracking systems.

Principles of Effective Nutrition Education

- Scientific Accuracy:

- Information should be based on evidence-based nutrition guidelines.

- Cultural Relevance:

- Advice should align with cultural and traditional food habits.

- Simplicity and Clarity:

- Messages should be easy to understand.

- Practical Application:

- Advice should be feasible for individuals to implement in daily life.

- Behavioral Approach:

- Focus on long-term dietary behavior change rather than short-term fixes.

Role of Nutrition Education in Disease Prevention

- Prevention of Malnutrition:

- Educating mothers on proper infant feeding (breastfeeding, complementary feeding).

- Obesity and Lifestyle Diseases:

- Promoting physical activity and balanced diets.

- Diabetes Management:

- Teaching carbohydrate counting and glycemic index concepts.

- Cardiovascular Disease Prevention:

- Encouraging reduction in salt, saturated fats, and processed foods.

- Food Safety and Hygiene:

- Preventing foodborne illnesses through proper cooking and storage techniques.

III. Comparison Between Nutrition Assessment and Nutrition Education

| Criteria | Nutrition Assessment | Nutrition Education |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Process of evaluating nutritional status. | Process of educating about nutrition. |

| Objective | Identify deficiencies, excesses, and risks. | Improve dietary habits and prevent diseases. |

| Methods Used | Anthropometric, biochemical, clinical, dietary. | Counseling, group programs, media campaigns. |

| Target Audience | Individuals, groups, populations. | Individuals, schools, workplaces, communities. |

| Outcome | Diagnosis of malnutrition, obesity, etc. | Awareness and behavior change in food habits. |

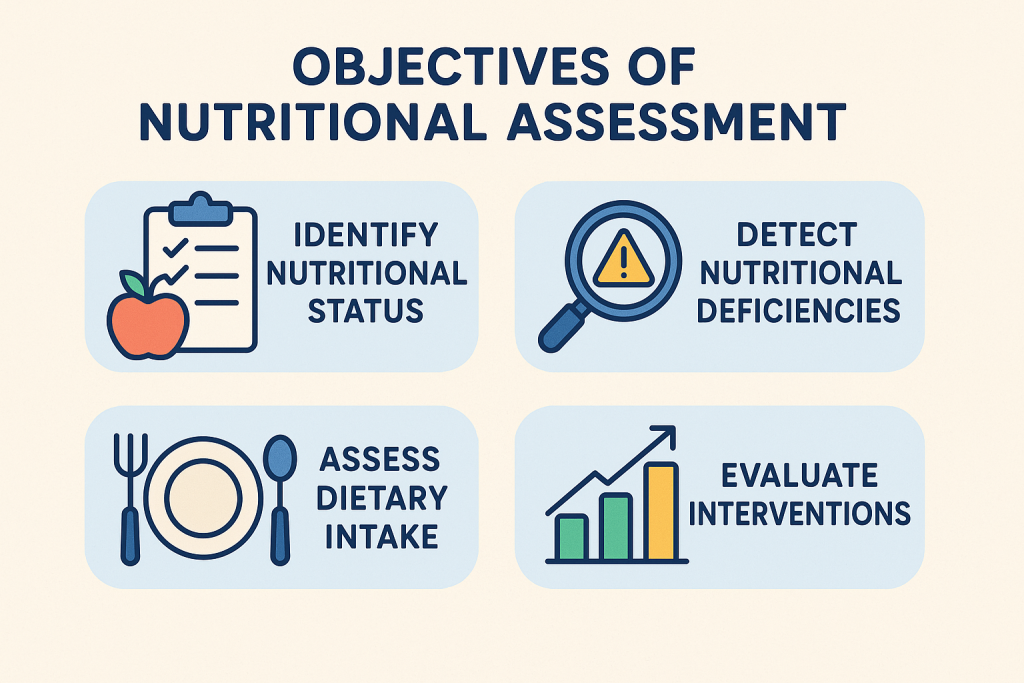

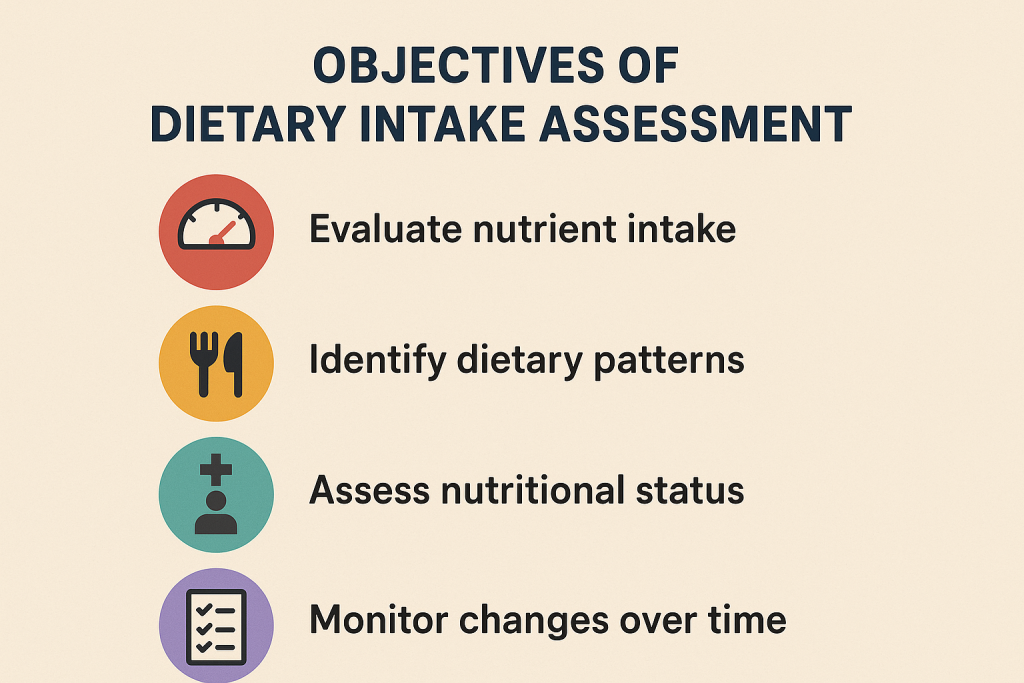

Objectives of Nutritional Assessment

Introduction

Nutritional assessment is the systematic process of collecting and analyzing information to determine an individual’s or a population’s nutritional status. It helps in identifying malnutrition, deficiencies, and diet-related diseases and guides appropriate interventions.

Objectives of Nutritional Assessment

The objectives of nutritional assessment can be categorized into different levels: individual, community, clinical, and public health levels. Below is a detailed breakdown of each objective:

1. Identify Nutritional Deficiencies and Malnutrition

- Detecting undernutrition:

- Identifies protein-energy malnutrition (e.g., marasmus, kwashiorkor).

- Detects deficiencies in vitamins and minerals (e.g., iron-deficiency anemia, scurvy, rickets).

- Detecting overnutrition:

- Identifies overweight and obesity, which increase the risk of non-communicable diseases.

- Evaluates excessive intake of fats, sugars, and processed foods.

2. Assess Nutritional Status and Growth

- For individuals:

- Evaluates whether a person’s dietary intake meets daily nutritional needs.

- Monitors growth in children (e.g., stunted growth, failure to thrive).

- For populations:

- Helps in large-scale nutrition surveys (e.g., NFHS – National Family Health Survey).

- Identifies regions with high malnutrition rates for targeted interventions.

3. Aid in the Diagnosis of Nutrition-Related Disorders

- Chronic diseases:

- Assesses diet-related risks for diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, and osteoporosis.

- Metabolic disorders:

- Helps diagnose conditions like metabolic syndrome and thyroid disorders.

- Food allergies and intolerances:

- Identifies conditions like lactose intolerance, gluten intolerance (celiac disease).

4. Guide Medical and Nutritional Interventions

- Develop personalized nutrition plans:

- Helps dietitians create individualized diet charts for patients (e.g., diabetic diet, renal diet).

- Determine the need for supplements:

- Identifies individuals who require vitamin or mineral supplements (e.g., folic acid for pregnancy).

- Monitor effectiveness of dietary interventions:

- Helps in tracking improvements after dietary modifications.

5. Evaluate the Impact of Nutritional Programs

- For public health policies:

- Measures the success of government nutrition programs like the Mid-Day Meal Scheme, POSHAN Abhiyaan.

- For clinical settings:

- Tracks recovery from malnutrition in hospital patients.

- For community programs:

- Assesses whether food fortification initiatives (e.g., iodized salt, fortified rice) are effective.

6. Support Dietary Planning and Policy Making

- In healthcare:

- Helps hospitals plan therapeutic diets for patients.

- In national programs:

- Assists governments in designing nutrition policies, such as food security and fortification strategies.

- In food industry:

- Guides food labeling laws and nutritional recommendations.

7. Prevent and Manage Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs)

- Heart disease prevention:

- Identifies high cholesterol levels and dietary fat intake.

- Diabetes management:

- Monitors carbohydrate intake and glycemic control.

- Hypertension prevention:

- Evaluates sodium intake and advises on dietary changes.

8. Monitor Special Nutritional Needs

- For pregnant and lactating women:

- Ensures adequate maternal nutrition to prevent low birth weight and developmental issues.

- For infants and children:

- Tracks growth and prevents stunted growth or wasting.

- For the elderly:

- Assesses risk factors for osteoporosis, vitamin deficiencies, and muscle loss (sarcopenia).

9. Identify Dietary Habits and Cultural Practices

- Understanding eating patterns:

- Evaluates whether diets are balanced, deficient, or excessive.

- Assessing food insecurity:

- Identifies populations that lack access to nutritious food.

- Evaluating cultural and religious food practices:

- Ensures dietary recommendations respect cultural beliefs and traditions.

10. Promote Nutritional Awareness and Education

- For individuals and families:

- Provides guidance on healthy eating habits.

- For schools and workplaces:

- Develops nutrition programs to promote healthy choices.

- For healthcare professionals:

- Trains doctors and nurses to incorporate nutrition into patient care.

11. Support Research in Nutrition and Public Health

- Clinical nutrition research:

- Assists in developing new dietary guidelines and recommendations.

- Epidemiological studies:

- Examines the relationship between diet and diseases at a population level.

- Innovations in food technology:

- Supports research on food fortification and functional foods.

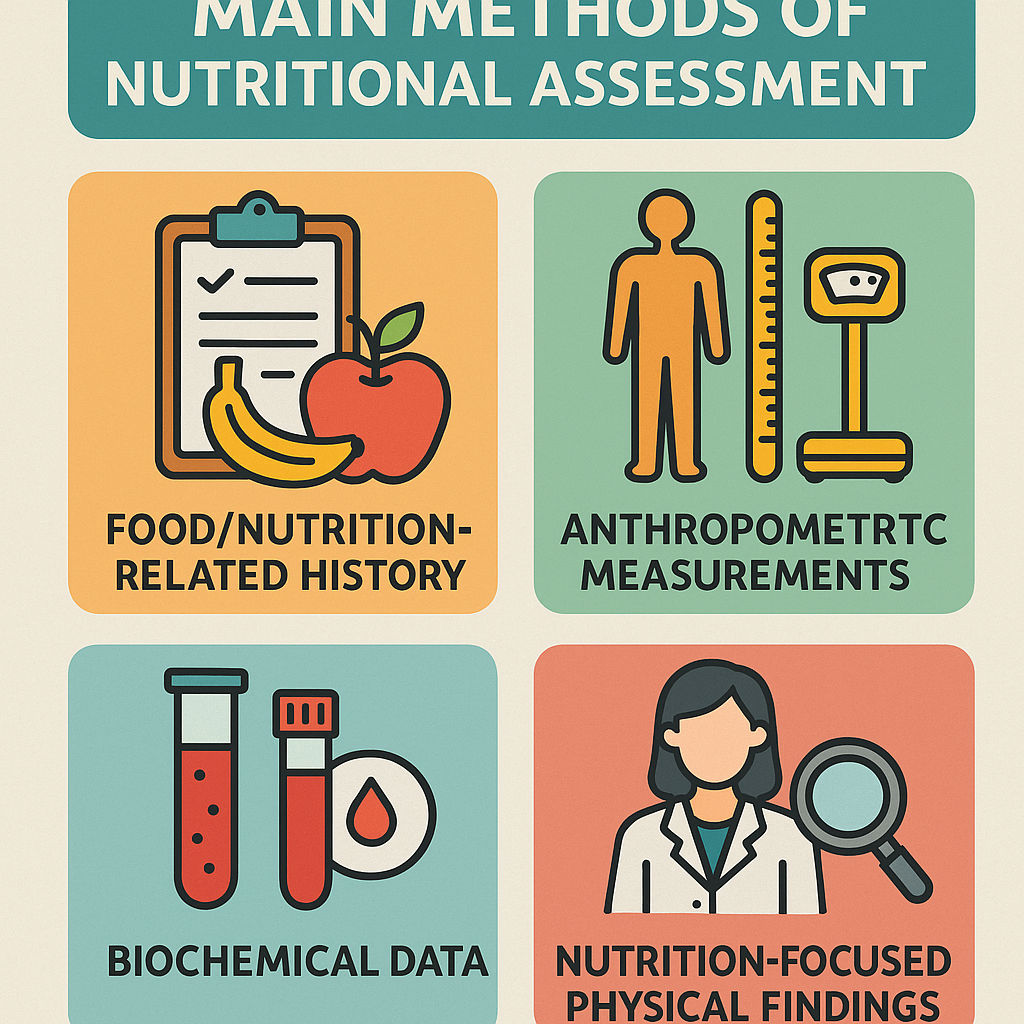

Methods of Nutritional Assessment

Introduction

Nutritional assessment is a comprehensive evaluation of an individual’s or population’s nutritional status. It is essential for identifying malnutrition, nutrient deficiencies, and diet-related health risks. The most widely used approach for nutritional assessment is the ABCD method, which includes Anthropometric, Biochemical, Clinical, and Dietary assessments. Additionally, functional and ecological methods play a role in population-wide assessments.

Main Methods of Nutritional Assessment (ABCD Approach)

1. Anthropometric Assessment (Measurement of Body Composition)

This method measures body size, proportions, and composition to assess nutritional status.

Common Anthropometric Measurements:

| Measurement | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Height | Assesses growth and development, detects stunted growth. |

| Weight | Indicates underweight, normal weight, overweight, or obesity. |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | Assesses overall body fat and weight categories. (BMI = Weight (kg) / Height² (m²)) |

| Mid-Upper Arm Circumference (MUAC) | Detects protein-energy malnutrition, especially in children and pregnant women. |

| Waist-to-Hip Ratio (WHR) | Determines the risk of cardiovascular diseases. |

| Waist-to-Height Ratio (WHtR) | Predicts obesity-related health risks. |

| Head Circumference | Used in infants to assess brain growth and malnutrition. |

| Skinfold Thickness (Calipers) | Estimates body fat percentage using measurements like triceps and subscapular skinfold thickness. |

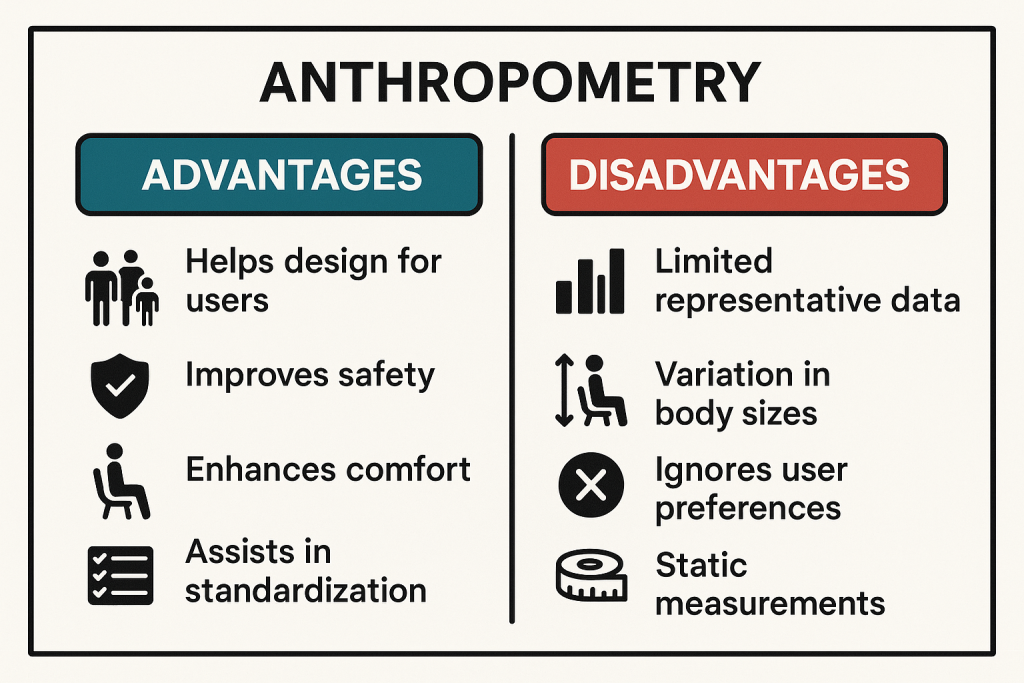

✅ Advantages:

- Non-invasive and easy to perform.

- Useful for large-scale screenings.

❌ Disadvantages:

- Does not measure micronutrient deficiencies.

- Can be affected by hydration status and measurement errors.

2. Biochemical (Laboratory) Assessment

This method measures nutrients, enzymes, or metabolic markers in blood, urine, or other tissues.

Common Biochemical Tests:

| Test | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (Hb) | Detects iron deficiency anemia. |

| Serum Albumin | Assesses protein status and overall nutritional health. |

| Serum Cholesterol & Triglycerides | Determines risk of cardiovascular diseases. |

| Blood Glucose (Fasting/Random, HbA1c) | Diagnoses and monitors diabetes. |

| Serum Vitamin D | Identifies vitamin D deficiency. |

| Serum Calcium & Phosphorus | Assesses bone health and risk of osteoporosis. |

| Serum Iron & Ferritin | Detects iron storage levels and deficiency. |

| Serum Electrolytes (Sodium, Potassium, Magnesium, etc.) | Evaluates hydration and metabolic balance. |

| Thyroid Function Tests (TSH, T3, T4) | Identifies thyroid-related nutritional disorders. |

| Urinary Iodine Excretion | Detects iodine deficiency. |

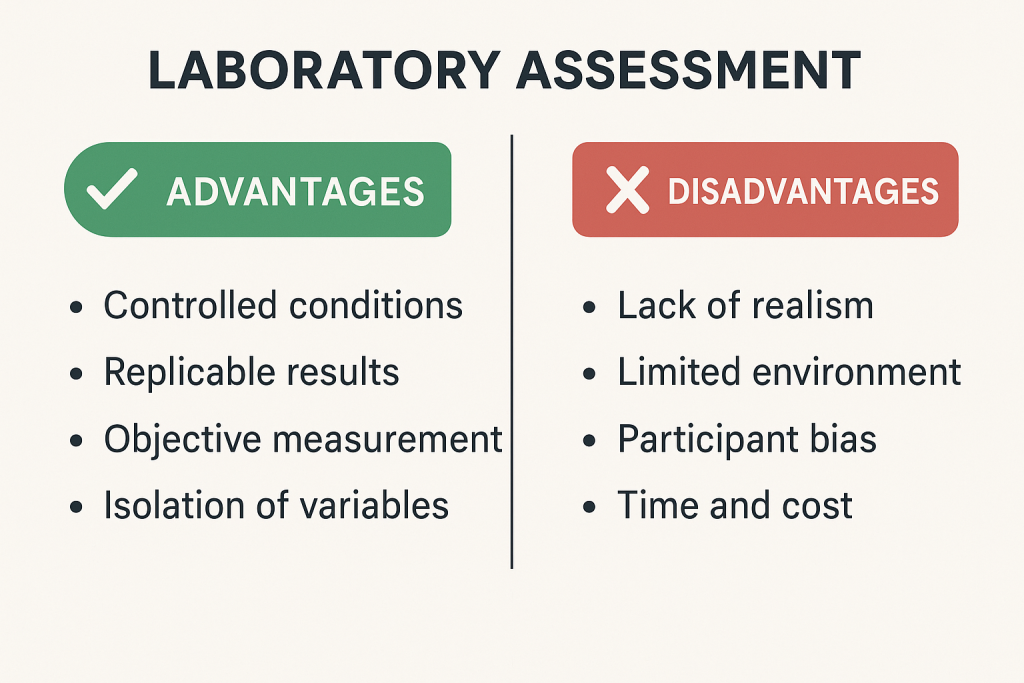

✅ Advantages:

- Detects early nutritional deficiencies before clinical symptoms appear.

- Provides objective and accurate results.

❌ Disadvantages:

- Expensive and not always accessible in rural areas.

- Requires trained personnel and laboratory facilities.

3. Clinical Assessment

This method involves a physical examination to identify visible signs and symptoms of nutrient deficiencies.

Common Clinical Signs of Nutritional Deficiencies:

| Deficiency | Clinical Signs |

|---|---|

| Iron Deficiency (Anemia) | Pale skin, fatigue, spoon-shaped nails. |

| Vitamin A Deficiency | Night blindness, dry eyes (xerophthalmia). |

| Vitamin B12 Deficiency | Tingling in hands and feet, memory problems. |

| Vitamin C Deficiency (Scurvy) | Bleeding gums, joint pain, poor wound healing. |

| Vitamin D & Calcium Deficiency | Bone pain, rickets in children, osteoporosis in adults. |

| Protein Deficiency (Kwashiorkor/Marasmus) | Edema, muscle wasting, thin hair. |

| Iodine Deficiency | Goiter (enlarged thyroid), mental retardation. |

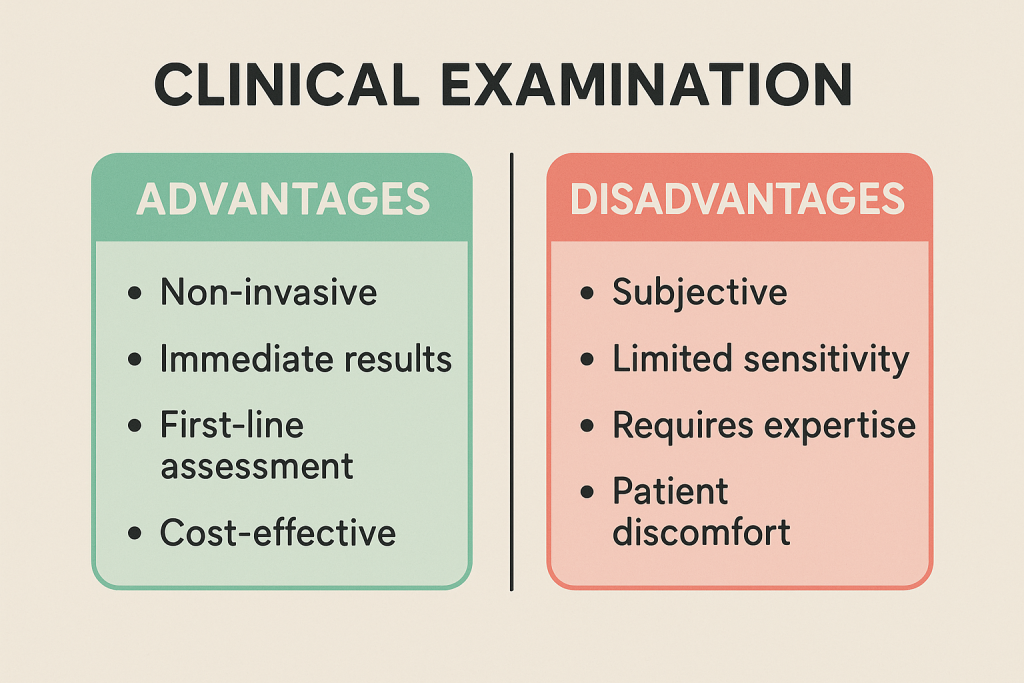

✅ Advantages:

- Quick and inexpensive.

- Useful for field assessments and mass screenings.

❌ Disadvantages:

- Requires trained professionals to interpret findings.

- Some symptoms may overlap with other medical conditions.

4. Dietary Assessment

This method evaluates food intake, eating habits, and dietary patterns.

Common Dietary Assessment Methods:

| Method | Description |

|---|---|

| 24-Hour Dietary Recall | Individual reports all food and beverages consumed in the past 24 hours. |

| Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) | Assesses how often specific foods are consumed over weeks or months. |

| Diet History | Detailed interview covering long-term food intake patterns. |

| Food Diary (Food Record) | Individual records food intake for 3-7 days. |

| Weighed Food Intake | Measuring and weighing all food before consumption. |

✅ Advantages:

- Identifies dietary deficiencies and imbalances.

- Helps in meal planning and diet modifications.

❌ Disadvantages:

- Recall bias – People may forget what they ate.

- Underreporting or overreporting due to social desirability bias.

Other Methods of Nutritional Assessment

5. Functional Assessment

- Evaluates how nutrition impacts body functions.

- Example tests:

- Grip Strength Test – Assesses muscle function (linked to protein intake).

- Cognitive Function Tests – Evaluates the impact of nutrition on brain health.

- Exercise Tolerance Tests – Determines fitness and endurance related to nutrition.

✅ Advantages:

- Shows the real impact of nutrition on daily life activities.

❌ Disadvantages:

- May not detect early micronutrient deficiencies.

6. Ecological and Socioeconomic Assessment

- Examines factors affecting food availability and nutritional choices.

- Includes:

- Food security status (availability and accessibility of nutritious food).

- Income level (affordability of healthy food).

- Cultural and traditional food habits (dietary patterns).

- Health policies and programs (government nutrition programs like Mid-Day Meals).

✅ Advantages:

- Useful for policy-making and large-scale nutrition programs.

- Identifies risk factors affecting an entire community’s nutrition.

❌ Disadvantages:

- Does not provide individual-level nutritional data.

Comparison of Nutritional Assessment Methods

| Method | Purpose | Example Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Anthropometric | Measures body size and growth. | BMI, MUAC, Skinfold Calipers. |

| Biochemical | Detects nutrient deficiencies in blood and urine. | Blood tests (Hb, cholesterol, vitamins). |

| Clinical | Identifies visible deficiency signs. | Physical examination (skin, eyes, nails). |

| Dietary | Evaluates food intake and patterns. | 24-hour recall, FFQ, food diary. |

| Functional | Assesses nutrition’s impact on physical function. | Grip strength, cognitive tests. |

| Ecological/Socioeconomic | Identifies external factors affecting nutrition. | Surveys, income analysis, food availability. |

Clinical Examination in Nutritional Assessment

Introduction

Clinical examination in nutritional assessment is a physical evaluation of an individual to detect visible signs and symptoms of malnutrition and nutrient deficiencies. It is a quick and cost-effective method, often used in combination with anthropometric, biochemical, and dietary assessments to diagnose nutritional disorders.

Objectives of Clinical Examination in Nutrition

- Identify physical signs of malnutrition (e.g., undernutrition, protein-energy malnutrition).

- Detect vitamin and mineral deficiencies (e.g., iron-deficiency anemia, scurvy, rickets).

- Assess overall health status and its relationship with nutrition.

- Monitor effects of nutritional interventions (e.g., weight gain in malnourished children).

- Support diagnosis of diet-related diseases (e.g., obesity, metabolic syndrome, diabetes).

Key Areas Assessed in Clinical Examination

1. General Appearance

| Observation | Possible Nutritional Deficiency/Condition |

|---|---|

| Pale skin, fatigue | Iron deficiency anemia |

| Thin, wasted body, sunken eyes | Protein-energy malnutrition (Marasmus) |

| Edema (swelling in legs, face) | Protein deficiency (Kwashiorkor) |

| Obesity, excess fat accumulation | Overnutrition, metabolic syndrome |

| Delayed wound healing | Vitamin C or zinc deficiency |

| Dry, scaly skin | Vitamin A, B-complex, or essential fatty acid deficiency |

2. Skin Examination

| Observation | Possible Nutritional Deficiency/Condition |

|---|---|

| Pale, dry skin | Iron, folic acid, or vitamin B12 deficiency |

| Scaly dermatitis | Essential fatty acid or vitamin B6 deficiency |

| Petechiae (small red spots on the skin) | Vitamin C or vitamin K deficiency |

| Hyperpigmentation (dark patches on the skin) | Niacin (Vitamin B3) deficiency – Pellagra |

| Cracks at the corners of the mouth (angular cheilitis) | Vitamin B2 (Riboflavin) deficiency |

| Yellowish tint to skin | Carotene excess or liver disease |

3. Hair Examination

| Observation | Possible Nutritional Deficiency/Condition |

|---|---|

| Thin, dry, brittle hair | Protein, biotin, or zinc deficiency |

| Easily pluckable hair | Severe protein-energy malnutrition (Kwashiorkor) |

| Premature graying | Vitamin B12 or copper deficiency |

| Flag sign (alternating light and dark bands in hair) | Protein-energy malnutrition |

4. Nail Examination

| Observation | Possible Nutritional Deficiency/Condition |

|---|---|

| Spoon-shaped nails (koilonychia) | Iron deficiency anemia |

| Brittle, ridged nails | Protein, zinc, or iron deficiency |

| White spots on nails (leukonychia) | Zinc or calcium deficiency |

| Pale or bluish nails | Vitamin B12 or iron deficiency |

5. Eye Examination

| Observation | Possible Nutritional Deficiency/Condition |

|---|---|

| Night blindness, dry eyes (Xerophthalmia) | Vitamin A deficiency |

| Pale conjunctiva (inner eyelid) | Iron deficiency anemia |

| Bitot’s spots (white patches on the conjunctiva) | Vitamin A deficiency |

| Blurred vision, cataracts | Vitamin E or Vitamin C deficiency |

| Red, inflamed conjunctiva | Vitamin B2 (Riboflavin) deficiency |

6. Mouth and Tongue Examination

| Observation | Possible Nutritional Deficiency/Condition |

|---|---|

| Swollen, bleeding gums | Vitamin C deficiency (Scurvy) |

| Glossitis (swollen, smooth tongue) | Vitamin B2, B3, B6, or iron deficiency |

| Angular stomatitis (cracks at mouth corners) | Vitamin B2, B6 deficiency |

| Dry mouth (Xerostomia) | Vitamin A or dehydration |

| Pale tongue | Iron or folic acid deficiency |

7. Teeth Examination

| Observation | Possible Nutritional Deficiency/Condition |

|---|---|

| Delayed eruption of teeth | Vitamin D or calcium deficiency |

| Dental cavities (tooth decay) | Excess sugar intake, vitamin D or fluoride deficiency |

| Loose teeth, gum infections | Vitamin C or calcium deficiency |

8. Neurological and Muscular Examination

| Observation | Possible Nutritional Deficiency/Condition |

|---|---|

| Muscle weakness, cramping | Magnesium or potassium deficiency |

| Numbness, tingling in hands and feet | Vitamin B12 or folic acid deficiency |

| Irritability, confusion, memory problems | Vitamin B1 (Thiamine) or B12 deficiency |

| Spasticity, difficulty in movement | Vitamin D deficiency (Rickets in children, Osteomalacia in adults) |

| Seizures or convulsions | Calcium, magnesium, or vitamin B6 deficiency |

9. Bone and Joint Examination

| Observation | Possible Nutritional Deficiency/Condition |

|---|---|

| Bowed legs (Rickets in children) | Vitamin D, calcium, or phosphorus deficiency |

| Fractures, osteoporosis (weak bones) | Calcium, vitamin D, or phosphorus deficiency |

| Joint pain, swelling | Vitamin C deficiency (Scurvy) |

10. Edema and Hydration Status

| Observation | Possible Nutritional Deficiency/Condition |

|---|---|

| Pitting edema (swelling in legs, feet, hands) | Protein deficiency (Kwashiorkor) |

| Dehydration (dry skin, sunken eyes, low urine output) | Water, sodium, or potassium deficiency |

| Overhydration (swollen limbs, weight gain) | Kidney dysfunction, sodium imbalance |

Advantages and Disadvantages of Clinical Examination

✅ Advantages:

- Quick, inexpensive, and does not require special equipment.

- Can be performed anywhere (hospitals, communities, schools).

- Helps in early identification of nutritional deficiencies.

❌ Disadvantages:

- Relies on visible signs, which may appear only in advanced deficiency stages.

- Requires trained healthcare professionals for accurate diagnosis.

- Some symptoms may overlap with non-nutritional diseases.

Comparison of Clinical Examination with Other Nutritional Assessment Methods

| Assessment Method | Purpose | Example Tools Used |

|---|---|---|

| Anthropometric | Measures body size and growth. | BMI, MUAC, weight, height. |

| Biochemical | Detects deficiencies in blood/urine. | Blood tests (Hb, cholesterol, vitamins). |

| Clinical | Identifies visible deficiency signs. | Physical examination (skin, nails, eyes, mouth). |

| Dietary | Evaluates food intake patterns. | 24-hour recall, food diary. |

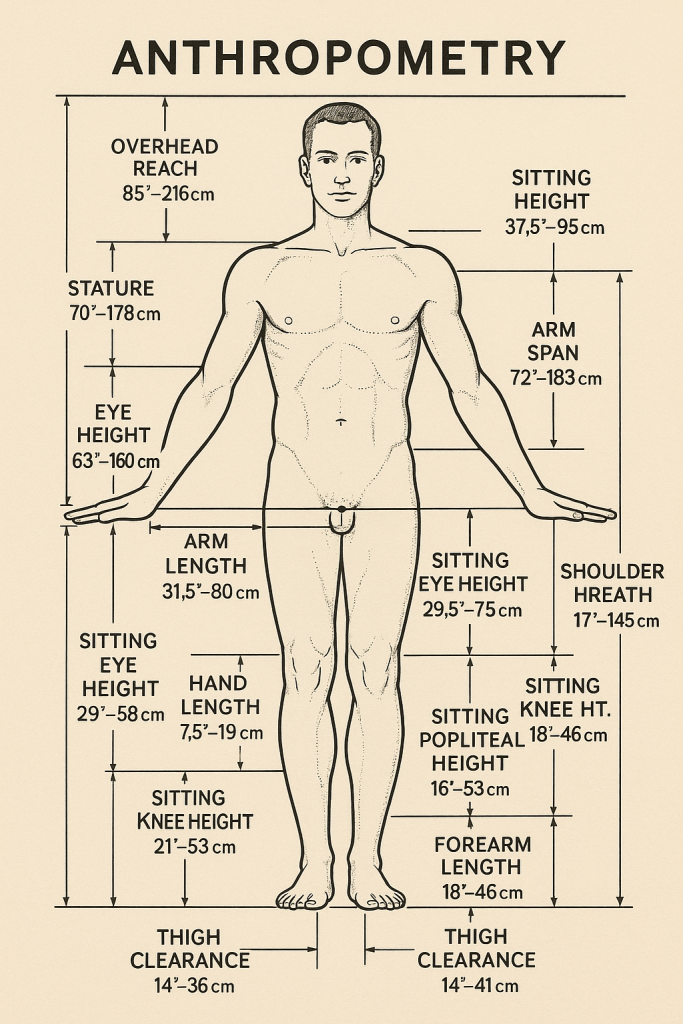

Anthropometry in Nutritional Assessment

Introduction

Anthropometry is the systematic measurement of the size, shape, and composition of the human body. It is widely used in nutritional assessment to evaluate growth, development, and body composition in individuals and populations.

Anthropometric measurements help identify:

- Malnutrition (underweight, stunting, wasting)

- Obesity and overweight

- Nutritional deficiencies

- Growth abnormalities

- Risk of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as diabetes and cardiovascular diseases

Objectives of Anthropometric Assessment

- Evaluate Nutritional Status (underweight, overweight, obesity).

- Assess Growth and Development (especially in infants and children).

- Monitor Changes in Body Composition over time.

- Identify Risk Factors for Chronic Diseases (hypertension, diabetes).

- Measure the Impact of Nutritional Interventions in communities.

- Support Clinical Diagnosis of nutrition-related disorders (protein-energy malnutrition, obesity).

Key Anthropometric Measurements and Their Uses

1. Weight Measurement

✅ Purpose:

- Determines body mass in relation to height.

- Helps in BMI calculation.

✅ Method:

- Use a calibrated weighing scale.

- Measured in kilograms (kg).

✅ Interpretation:

- Low weight = Underweight, malnutrition.

- Excess weight = Overweight, obesity.

2. Height (Stature) Measurement

✅ Purpose:

- Assesses growth in children and adolescents.

- Used with weight to calculate BMI.

✅ Method:

- Measured using a stadiometer.

- Person should stand straight, without shoes.

✅ Interpretation:

- Short stature (stunting) = Chronic malnutrition.

- Tall stature = Normal or excessive growth (gigantism in rare cases).

3. Body Mass Index (BMI)

✅ Purpose:

- Classifies underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obesity.

✅ Formula: BMI=Weight (kg)Height (m)2BMI = \frac{{\text{Weight (kg)}}}{{\text{Height (m)}^2}}BMI=Height (m)2Weight (kg)

✅ Interpretation (WHO BMI Classification):

| BMI Range (kg/m²) | Classification |

|---|---|

| < 16.0 | Severe underweight |

| 16.0 – 16.9 | Moderate underweight |

| 17.0 – 18.4 | Mild underweight |

| 18.5 – 24.9 | Normal weight |

| 25.0 – 29.9 | Overweight |

| 30.0 – 34.9 | Obesity Class I |

| 35.0 – 39.9 | Obesity Class II |

| ≥ 40.0 | Obesity Class III (Severe obesity) |

✅ Clinical Use:

- Low BMI suggests undernutrition, chronic illness.

- High BMI is linked to obesity, diabetes, hypertension.

4. Mid-Upper Arm Circumference (MUAC)

✅ Purpose:

- Assesses malnutrition in children and pregnant women.

- Quick and useful in field settings.

✅ Method:

- Measured at the midpoint of the upper arm (between the shoulder and elbow).

- Uses a MUAC tape.

✅ Interpretation for Children (6 months – 5 years):

| MUAC (cm) | Nutritional Status |

|---|---|

| ≥ 12.5 cm | Normal |

| 11.5 – 12.4 cm | Moderate Acute Malnutrition (MAM) |

| < 11.5 cm | Severe Acute Malnutrition (SAM) |

✅ Interpretation for Pregnant Women:

- MUAC < 23 cm → Malnourished.

- MUAC ≥ 23 cm → Normal.

✅ Clinical Use:

- Used in community health programs (e.g., UNICEF malnutrition screening).

- Low MUAC indicates protein-energy malnutrition.

5. Head Circumference

✅ Purpose:

- Measures brain growth in infants and young children.

✅ Method:

- Measured using a non-stretchable measuring tape around the forehead and occipital bone.

✅ Interpretation:

- Small head size (Microcephaly): Suggests malnutrition, genetic disorder, or infection.

- Large head size (Macrocephaly): Can indicate hydrocephalus or brain abnormalities.

✅ Clinical Use:

- Newborn and infant growth monitoring.

- Early detection of developmental disorders.

6. Waist Circumference

✅ Purpose:

- Measures central (abdominal) obesity, which is linked to metabolic diseases.

✅ Method:

- Measured at the midpoint between the last rib and iliac crest using a measuring tape.

✅ Interpretation (WHO Standards):

| Waist Circumference | Risk Level |

|---|---|

| Men < 94 cm (37 inches) | Normal |

| Men ≥ 94 cm | Increased risk of metabolic diseases |

| Women < 80 cm (31.5 inches) | Normal |

| Women ≥ 80 cm | Increased risk of metabolic diseases |

✅ Clinical Use:

- Higher waist circumference is associated with diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases.

7. Waist-to-Hip Ratio (WHR)

✅ Purpose:

- Measures fat distribution (apple-shaped or pear-shaped body).

✅ Formula: WHR=Waist Circumference (cm)

Hip Circumference (cm)WHR

= \frac{{\text{Waist Circumference (cm)

}}}{{\text{Hip Circumference (cm)

}}}WHR=Hip Circumference (cm)

Waist Circumference (cm)

✅ Interpretation (WHO Standards):

| WHR | Risk Level for Metabolic Diseases |

|---|---|

| Men ≤ 0.90 | Normal |

| Men > 0.90 | High risk |

| Women ≤ 0.85 | Normal |

| Women > 0.85 | High risk |

✅ Clinical Use:

- High WHR is linked to heart disease, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes.

8. Skinfold Thickness Measurement

✅ Purpose:

- Assesses body fat percentage.

- Indicates nutritional reserves.

✅ Method:

- Uses calipers to measure subcutaneous fat at specific sites (e.g., triceps, subscapular).

✅ Clinical Use:

- Higher values indicate obesity.

- Lower values suggest underweight/malnutrition.

Comparison of Anthropometric Measurements

| Measurement | Purpose | Clinical Use |

|---|---|---|

| Weight | Measures body mass | Identifies underweight, overweight, obesity |

| Height | Assesses growth | Detects stunting or growth issues |

| BMI | Assesses weight category | Diagnoses obesity, malnutrition |

| MUAC | Measures muscle and fat stores | Used for malnutrition screening |

| Waist Circumference | Detects abdominal obesity | Predicts metabolic disorders |

| WHR | Measures fat distribution | Assesses cardiovascular risk |

| Skinfold Thickness | Measures body fat % | Evaluates obesity and nutritional reserves |

Advantages and Disadvantages of Anthropometry

✅ Advantages:

- Simple, non-invasive, and cost-effective.

- Can be used in both clinical and community settings.

- Useful for monitoring growth and screening malnutrition.

❌ Disadvantages:

- Does not assess micronutrient deficiencies.

- Requires trained personnel for accuracy.

- Results may be influenced by hydration status and posture.

Laboratory Assessment in Nutritional Assessment

Introduction

Laboratory (biochemical) assessment is a method of evaluating nutritional status by analyzing biological samples such as blood, urine, stool, and hair. It helps in detecting micronutrient deficiencies, metabolic disorders, and chronic disease risks that are not always visible through clinical or anthropometric assessments.

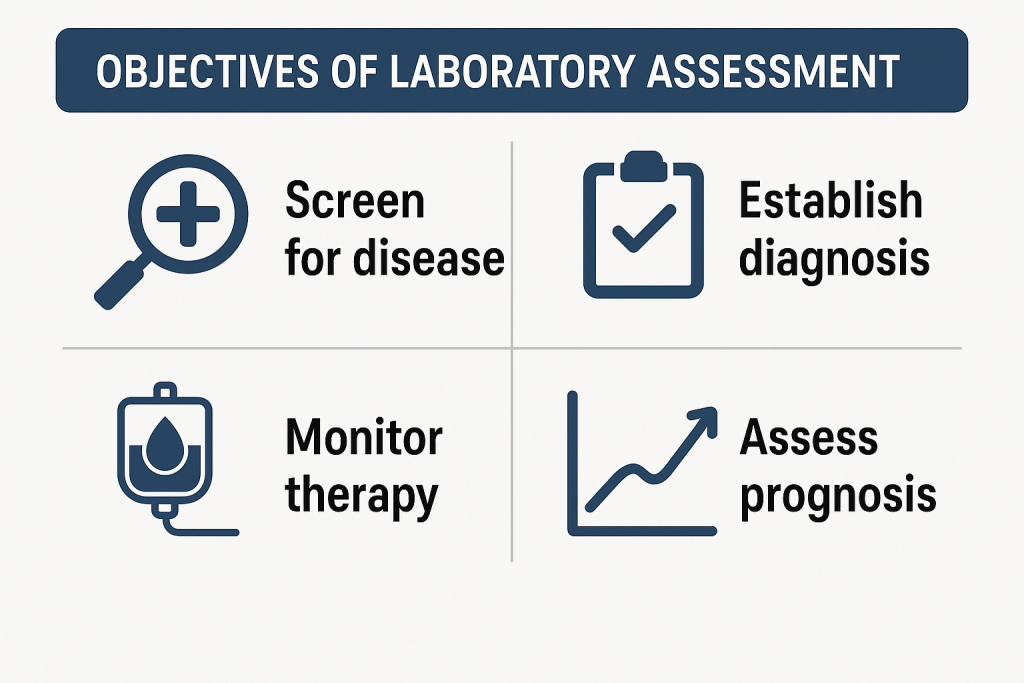

Objectives of Laboratory Assessment

- Detect early nutritional deficiencies before clinical symptoms appear.

- Monitor changes in nutritional status over time.

- Assess the effectiveness of dietary interventions and supplementation.

- Diagnose malnutrition-related disorders such as anemia, osteoporosis, and protein-energy malnutrition.

- Identify risk factors for non-communicable diseases (NCDs) like diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic syndrome.

Types of Laboratory Assessments and Their Uses

Laboratory tests can be grouped based on the type of nutrients or metabolic markers they evaluate.

1. Protein and Energy Status

✅ Purpose: Evaluates protein intake and malnutrition risk.

✅ Common Tests:

| Test | Purpose | Normal Range |

|---|---|---|

| Serum Albumin | Assesses long-term protein status. | 3.5 – 5.0 g/dL |

| Serum Prealbumin | Detects early protein malnutrition. | 16 – 40 mg/dL |

| Total Protein | Measures total body protein levels. | 6.0 – 8.3 g/dL |

| Creatinine-Height Index (CHI) | Indicates muscle mass depletion. | 80 – 100% (Normal) |

| Nitrogen Balance Test | Assesses protein metabolism. | Positive (> 0) in growth and pregnancy, Negative (< 0) in malnutrition |

✅ Clinical Use:

- Low albumin/prealbumin → Protein-energy malnutrition (Kwashiorkor, Marasmus).

- Low creatinine → Muscle wasting due to malnutrition.

2. Iron and Hematological Assessment (Anemia Detection)

✅ Purpose: Identifies iron-deficiency anemia and other blood-related disorders.

✅ Common Tests:

| Test | Purpose | Normal Range |

|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (Hb) | Measures oxygen-carrying capacity of blood. | ♂: 13.5 – 17.5 g/dL, ♀: 12.0 – 15.5 g/dL |

| Hematocrit (Hct) | Measures percentage of red blood cells. | ♂: 38 – 50%, ♀: 35 – 47% |

| Serum Iron | Assesses iron levels in the blood. | 60 – 170 µg/dL |

| Serum Ferritin | Measures iron storage. | ♂: 12 – 300 ng/mL, ♀: 12 – 150 ng/mL |

| Total Iron Binding Capacity (TIBC) | Measures iron transport capacity. | 250 – 450 µg/dL |

| Transferrin Saturation | Assesses iron transport efficiency. | 15 – 50% |

✅ Clinical Use:

- Low Hb, Hct, serum iron, ferritin → Iron-deficiency anemia.

- High TIBC, low transferrin saturation → Iron-deficiency anemia.

- High serum ferritin → Inflammation or iron overload (Hemochromatosis).

3. Vitamin Assessment

✅ Purpose: Identifies vitamin deficiencies affecting health.

✅ Common Tests:

| Vitamin | Test | Normal Range | Deficiency Disease |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin A | Serum Retinol | 30 – 80 µg/dL | Night blindness, Xerophthalmia |

| Vitamin D | Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D | 20 – 50 ng/mL | Rickets, Osteomalacia |

| Vitamin E | Serum Alpha-Tocopherol | 5 – 20 mg/L | Neurological problems |

| Vitamin K | Prothrombin Time (PT) | 11 – 13.5 sec | Bleeding disorders |

| Vitamin B1 (Thiamine) | Blood Thiamine Level | 70 – 180 nmol/L | Beriberi |

| Vitamin B2 (Riboflavin) | Serum Riboflavin | 6 – 50 µg/L | Angular stomatitis, glossitis |

| Vitamin B3 (Niacin) | Urinary N-methylnicotinamide | > 1.6 mg/g creatinine | Pellagra |

| Vitamin B6 (Pyridoxine) | Serum PLP (Pyridoxal Phosphate) | 5 – 50 ng/mL | Neuropathy, anemia |

| Vitamin B12 | Serum Vitamin B12 | 200 – 900 pg/mL | Pernicious anemia, neuropathy |

| Folate (Vitamin B9) | Serum Folate | 2 – 20 ng/mL | Megaloblastic anemia |

✅ Clinical Use:

- Low serum Vitamin D → Risk of osteoporosis, bone fractures.

- Low Vitamin B12, folate → Megaloblastic anemia, neurological disorders.

- Low Vitamin A → Night blindness, dry eyes.

4. Mineral and Electrolyte Assessment

✅ Purpose: Evaluates essential minerals required for metabolism and physiological functions.

✅ Common Tests:

| Mineral | Test | Normal Range | Deficiency Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium | Serum Calcium | 8.5 – 10.2 mg/dL | Osteoporosis, muscle cramps |

| Phosphorus | Serum Phosphate | 2.5 – 4.5 mg/dL | Weak bones, fatigue |

| Magnesium | Serum Magnesium | 1.7 – 2.2 mg/dL | Weakness, arrhythmia |

| Sodium (Na) | Serum Sodium | 135 – 145 mEq/L | Dehydration, confusion |

| Potassium (K) | Serum Potassium | 3.5 – 5.0 mEq/L | Muscle weakness, heart issues |

| Zinc | Serum Zinc | 60 – 130 µg/dL | Delayed wound healing, hair loss |

| Iodine | Urinary Iodine Excretion | 100 – 199 µg/L | Goiter, hypothyroidism |

✅ Clinical Use:

- Low serum calcium, phosphorus → Risk of rickets, osteomalacia.

- Low magnesium → Muscle spasms, cardiac arrhythmias.

- Low sodium, potassium → Electrolyte imbalance, dehydration.

5. Blood Glucose and Lipid Profile

✅ Purpose: Evaluates risk for diabetes and cardiovascular diseases.

✅ Common Tests:

| Test | Purpose | Normal Range |

|---|---|---|

| Fasting Blood Glucose | Diabetes screening | 70 – 100 mg/dL |

| HbA1c | Long-term glucose control | < 5.7% (Normal), > 6.5% (Diabetes) |

| Total Cholesterol | Heart disease risk | < 200 mg/dL |

| LDL (Bad Cholesterol) | Atherosclerosis risk | < 100 mg/dL |

| HDL (Good Cholesterol) | Protective against heart disease | > 40 mg/dL |

| Triglycerides | Fat storage assessment | < 150 mg/dL |

✅ Clinical Use:

- High blood glucose, HbA1c → Diabetes.

- High LDL, triglycerides → Risk of heart disease, stroke.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Laboratory Assessment

✅ Advantages:

- Detects hidden deficiencies before symptoms appear.

- Highly accurate and reliable.

- Useful for diagnosing chronic diseases.

❌ Disadvantages:

- Expensive and requires laboratory facilities.

- Invasive (requires blood/urine samples).

- Results may be affected by recent diet or hydration status.

Biochemical Assessment in Nutritional Assessment

Introduction

Biochemical assessment is a laboratory-based method used to evaluate an individual’s nutritional status by measuring nutrients, metabolites, and biomarkers in blood, urine, stool, hair, and other body fluids. It helps in detecting nutritional deficiencies, metabolic disorders, and chronic disease risks that are not always visible through clinical or anthropometric assessments.

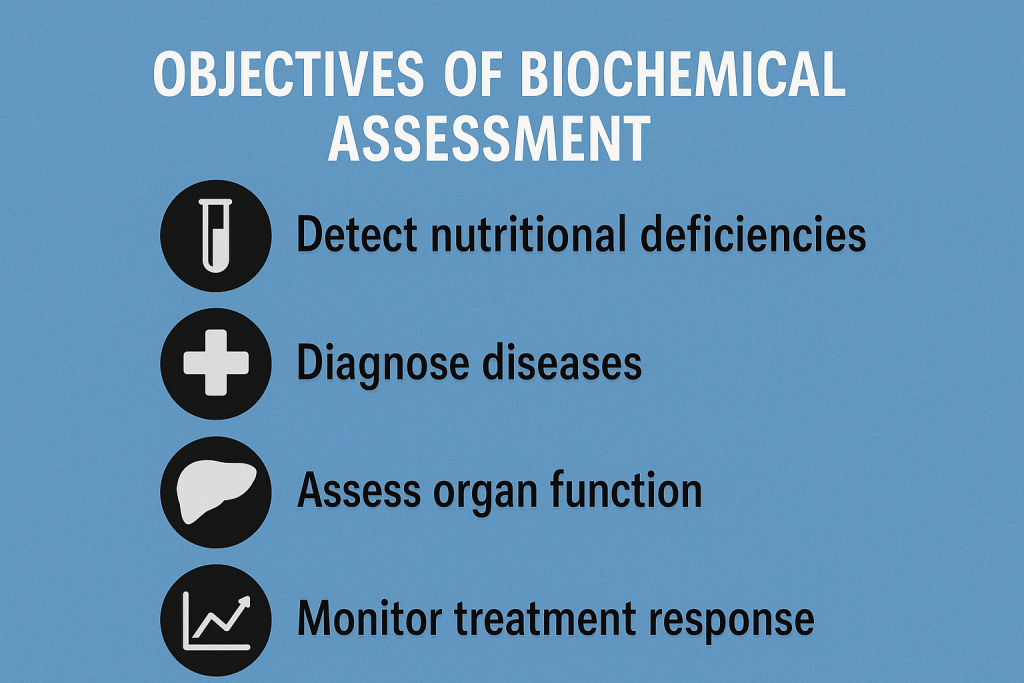

Objectives of Biochemical Assessment

- Detect early nutritional deficiencies before clinical symptoms appear.

- Monitor changes in nutritional status over time.

- Assess the effectiveness of dietary interventions and supplementation.

- Diagnose malnutrition-related disorders such as anemia, osteoporosis, and protein-energy malnutrition.

- Identify risk factors for non-communicable diseases (NCDs) like diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic syndrome.

- Evaluate organ function related to metabolism and nutrient utilization (liver, kidney, thyroid function).

Types of Biochemical Assessments and Their Uses

Biochemical tests are classified based on the type of nutrients or metabolic markers they evaluate.

1. Protein and Energy Status

✅ Purpose: Evaluates protein intake, muscle mass, and malnutrition risk.

✅ Common Tests:

| Test | Purpose | Normal Range |

|---|---|---|

| Serum Albumin | Assesses long-term protein status. | 3.5 – 5.0 g/dL |

| Serum Prealbumin | Detects early protein malnutrition. | 16 – 40 mg/dL |

| Total Protein | Measures total body protein levels. | 6.0 – 8.3 g/dL |

| Creatinine-Height Index (CHI) | Indicates muscle mass depletion. | 80 – 100% (Normal) |

| Nitrogen Balance Test | Assesses protein metabolism. | Positive (> 0) in growth and pregnancy, Negative (< 0) in malnutrition |

✅ Clinical Use:

- Low albumin/prealbumin → Protein-energy malnutrition (Kwashiorkor, Marasmus).

- Low creatinine → Muscle wasting due to malnutrition.

2. Iron and Hematological Assessment (Anemia Detection)

✅ Purpose: Identifies iron-deficiency anemia and other blood-related disorders.

✅ Common Tests:

| Test | Purpose | Normal Range |

|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (Hb) | Measures oxygen-carrying capacity of blood. | ♂: 13.5 – 17.5 g/dL, ♀: 12.0 – 15.5 g/dL |

| Hematocrit (Hct) | Measures percentage of red blood cells. | ♂: 38 – 50%, ♀: 35 – 47% |

| Serum Iron | Assesses iron levels in the blood. | 60 – 170 µg/dL |

| Serum Ferritin | Measures iron storage. | ♂: 12 – 300 ng/mL, ♀: 12 – 150 ng/mL |

| Total Iron Binding Capacity (TIBC) | Measures iron transport capacity. | 250 – 450 µg/dL |

| Transferrin Saturation | Assesses iron transport efficiency. | 15 – 50% |

✅ Clinical Use:

- Low Hb, Hct, serum iron, ferritin → Iron-deficiency anemia.

- High TIBC, low transferrin saturation → Iron-deficiency anemia.

- High serum ferritin → Inflammation or iron overload (Hemochromatosis).

3. Vitamin Assessment

✅ Purpose: Identifies vitamin deficiencies affecting health.

✅ Common Tests:

| Vitamin | Test | Normal Range | Deficiency Disease |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin A | Serum Retinol | 30 – 80 µg/dL | Night blindness, Xerophthalmia |

| Vitamin D | Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D | 20 – 50 ng/mL | Rickets, Osteomalacia |

| Vitamin E | Serum Alpha-Tocopherol | 5 – 20 mg/L | Neurological problems |

| Vitamin K | Prothrombin Time (PT) | 11 – 13.5 sec | Bleeding disorders |

| Vitamin B1 (Thiamine) | Blood Thiamine Level | 70 – 180 nmol/L | Beriberi |

| Vitamin B2 (Riboflavin) | Serum Riboflavin | 6 – 50 µg/L | Angular stomatitis, glossitis |

| Vitamin B3 (Niacin) | Urinary N-methylnicotinamide | > 1.6 mg/g creatinine | Pellagra |

| Vitamin B6 (Pyridoxine) | Serum PLP (Pyridoxal Phosphate) | 5 – 50 ng/mL | Neuropathy, anemia |

| Vitamin B12 | Serum Vitamin B12 | 200 – 900 pg/mL | Pernicious anemia, neuropathy |

| Folate (Vitamin B9) | Serum Folate | 2 – 20 ng/mL | Megaloblastic anemia |

✅ Clinical Use:

- Low serum Vitamin D → Risk of osteoporosis, bone fractures.

- Low Vitamin B12, folate → Megaloblastic anemia, neurological disorders.

- Low Vitamin A → Night blindness, dry eyes.

4. Mineral and Electrolyte Assessment

✅ Purpose: Evaluates essential minerals required for metabolism and physiological functions.

✅ Common Tests:

| Mineral | Test | Normal Range | Deficiency Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium | Serum Calcium | 8.5 – 10.2 mg/dL | Osteoporosis, muscle cramps |

| Phosphorus | Serum Phosphate | 2.5 – 4.5 mg/dL | Weak bones, fatigue |

| Magnesium | Serum Magnesium | 1.7 – 2.2 mg/dL | Weakness, arrhythmia |

| Sodium (Na) | Serum Sodium | 135 – 145 mEq/L | Dehydration, confusion |

| Potassium (K) | Serum Potassium | 3.5 – 5.0 mEq/L | Muscle weakness, heart issues |

| Zinc | Serum Zinc | 60 – 130 µg/dL | Delayed wound healing, hair loss |

| Iodine | Urinary Iodine Excretion | 100 – 199 µg/L | Goiter, hypothyroidism |

✅ Clinical Use:

- Low serum calcium, phosphorus → Risk of rickets, osteomalacia.

- Low magnesium → Muscle spasms, cardiac arrhythmias.

- Low sodium, potassium → Electrolyte imbalance, dehydration.

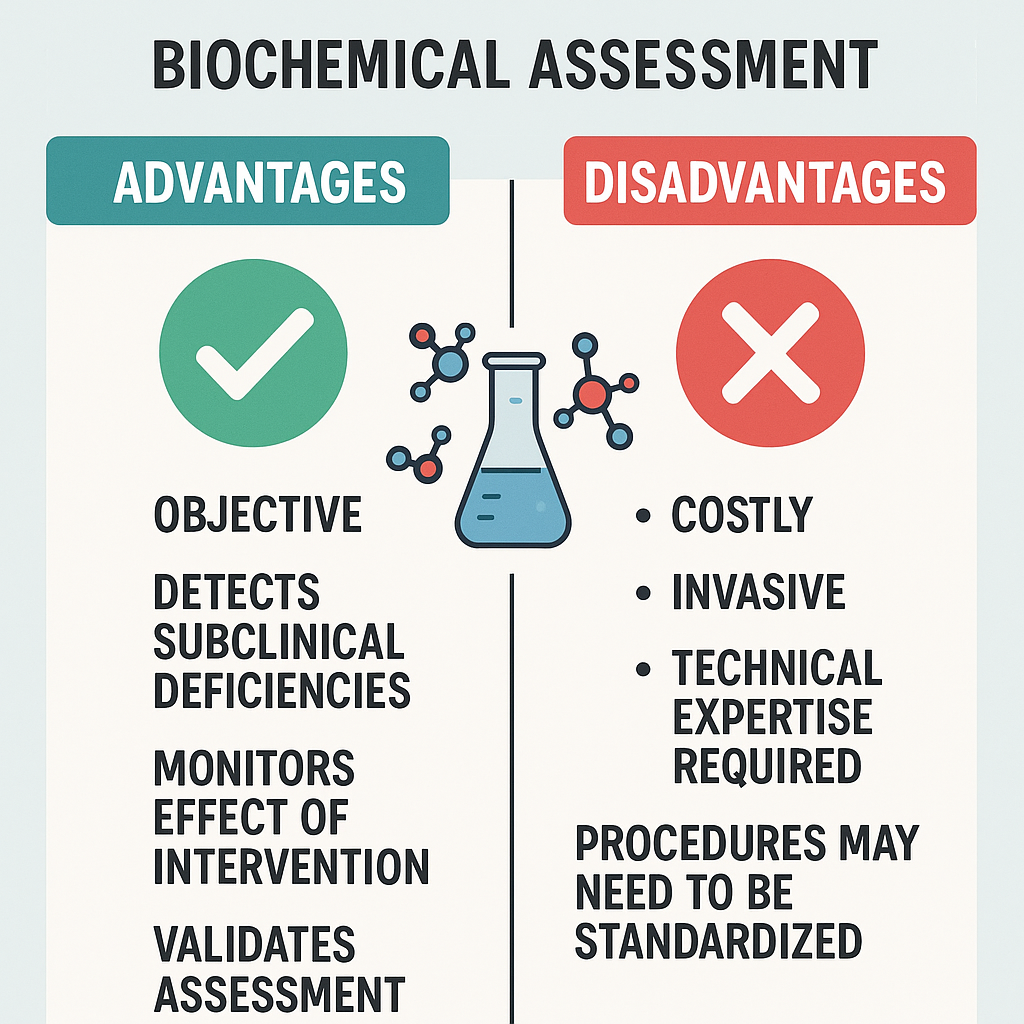

Advantages and Disadvantages of Biochemical Assessment

✅ Advantages:

- Detects hidden deficiencies before symptoms appear.

- Highly accurate and reliable.

- Useful for diagnosing chronic diseases.

❌ Disadvantages:

- Expensive and requires laboratory facilities.

- Invasive (requires blood/urine samples).

- Results may be affected by recent diet or hydration status.

Assessment of Dietary Intake Including Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) Method

Introduction

Dietary intake assessment is the process of evaluating an individual’s or population’s food consumption patterns to determine their nutritional status and dietary habits. It helps identify nutrient deficiencies, overnutrition, and dietary risk factors associated with diseases.

Several dietary assessment methods exist, including 24-hour dietary recall, food frequency questionnaire (FFQ), diet history, food records (food diary), and weighed food intake. Among these, the Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) is one of the most commonly used tools for assessing habitual dietary intake over time.

Objectives of Dietary Intake Assessment

- Evaluate dietary patterns and habits over time.

- Identify nutrient deficiencies and excesses in individuals or populations.

- Assess the adequacy of energy and nutrient intake based on dietary recommendations.

- Detect diet-related risk factors for diseases (e.g., obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases).

- Monitor dietary changes after nutritional interventions.

- Support public health and research studies to improve food and nutrition policies.

Methods of Dietary Intake Assessment

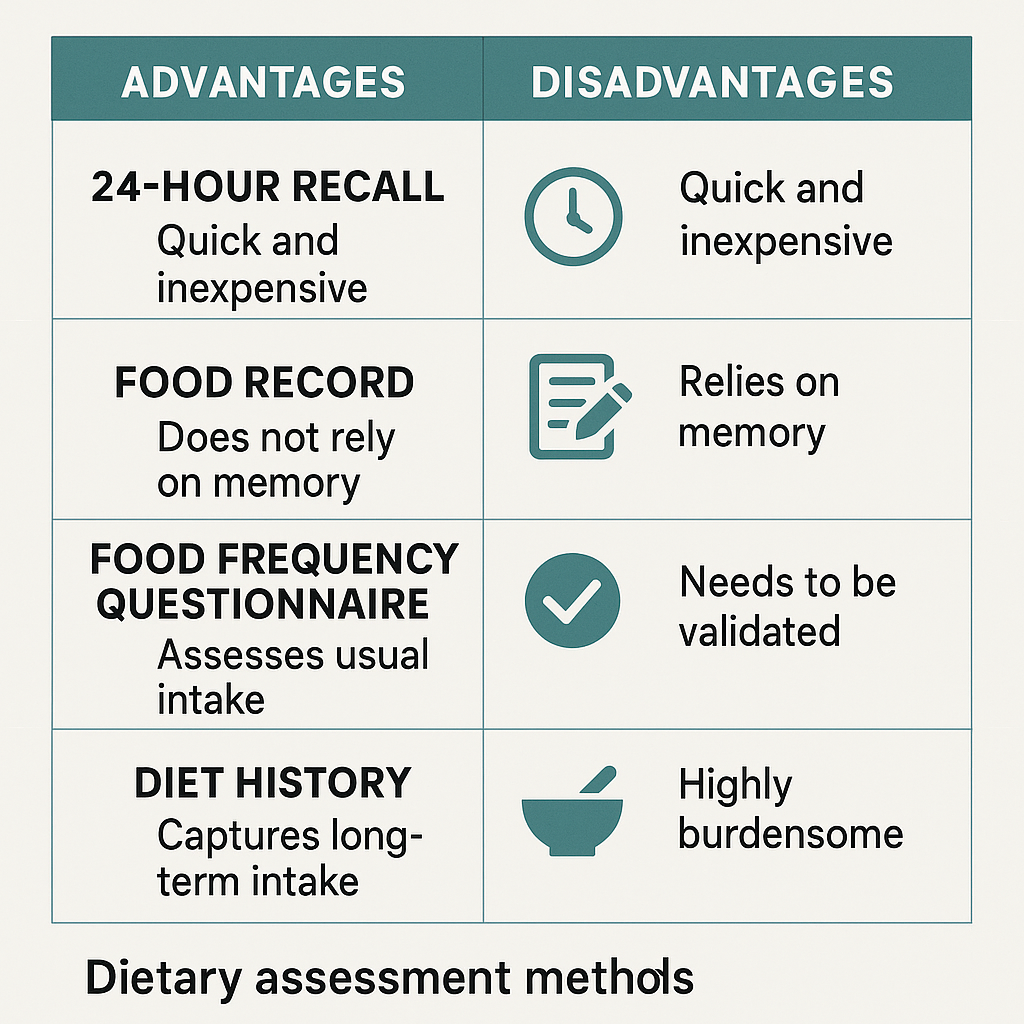

1. 24-Hour Dietary Recall

✅ Description:

- Individual reports all foods and beverages consumed in the past 24 hours.

- Interview-based recall of portion sizes, cooking methods, and meal times.

✅ Advantages:

- Quick and easy to administer.

- Suitable for large populations.

- Provides accurate short-term intake data.

❌ Disadvantages:

- Relies on memory → recall bias.

- Does not reflect long-term intake.

- Underreporting or overreporting is common.

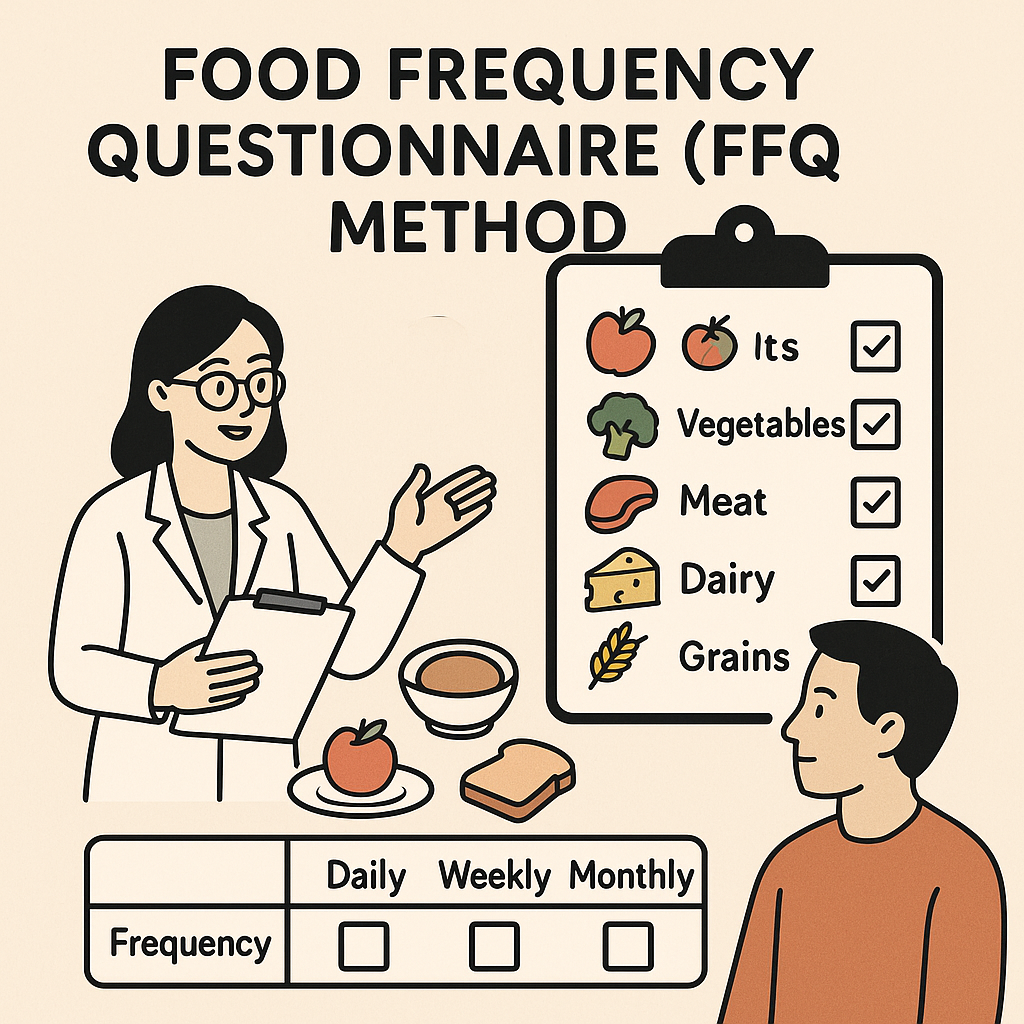

2. Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ)

✅ Description:

- A structured questionnaire that assesses how frequently specific foods or food groups are consumed over a defined period (week, month, or year).

- It provides habitual dietary patterns rather than short-term intake.

✅ Types of FFQ:

- Non-Quantitative FFQ – Records only frequency (e.g., How often do you consume milk? Daily, Weekly, Monthly).

- Semi-Quantitative FFQ – Includes portion size estimation (e.g., Small, Medium, Large).

- Quantitative FFQ – Provides detailed portion sizes and nutrient calculations.

✅ Example of an FFQ Format:

| Food Item | Daily | Weekly | Monthly | Rarely/Never |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milk/Yogurt | ⬜ | ⬜ | ⬜ | ⬜ |

| Rice/Wheat | ⬜ | ⬜ | ⬜ | ⬜ |

| Vegetables | ⬜ | ⬜ | ⬜ | ⬜ |

| Fruits | ⬜ | ⬜ | ⬜ | ⬜ |

| Meat/Fish | ⬜ | ⬜ | ⬜ | ⬜ |

✅ Advantages of FFQ:

- Captures long-term dietary patterns.

- Less burden on respondents compared to food diaries.

- Useful for large-scale epidemiological studies.

- Can be self-administered or interviewer-administered.

❌ Disadvantages of FFQ:

- Relies on memory → recall bias.

- Limited accuracy in estimating portion sizes.

- Predefined food list may not include all consumed foods.

✅ Clinical and Research Use of FFQ:

- Used in dietary epidemiology (e.g., linking diet with chronic diseases).

- Monitors trends in food consumption over months/years.

- Identifies dietary risk factors for obesity, diabetes, and heart disease.

3. Diet History Method

✅ Description:

- In-depth interview about usual food intake, meal patterns, portion sizes, and food preparation methods.

- Covers seasonal variations and cultural influences in diet.

✅ Advantages:

- Comprehensive and detailed.

- Identifies long-term dietary patterns.

- Can be personalized for individuals.

❌ Disadvantages:

- Time-consuming and requires skilled interviewers.

- Prone to recall bias and overestimation.

- Difficult for large-scale population studies.

4. Food Diary (Food Record)

✅ Description:

- The individual records all foods and beverages consumed over 3-7 days.

- Includes portion sizes, cooking methods, and meal times.

✅ Advantages:

- Accurate as it does not rely on memory.

- Captures daily variations in intake.

- Useful for weight management programs.

❌ Disadvantages:

- High participant burden → compliance issues.

- May alter normal eating habits due to recording process.

- Time-consuming and requires trained analysts.

5. Weighed Food Intake Method

✅ Description:

- The most precise method, where all foods and beverages are weighed before consumption.

- Used in research studies and clinical trials.

✅ Advantages:

- Highly accurate and reliable.

- Eliminates recall bias.

❌ Disadvantages:

- Difficult for large populations.

- Time-consuming and expensive.

- Not practical for routine assessments.

Comparison of Dietary Assessment Methods

| Method | Data Collection | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24-Hour Recall | Single day food recall | Quick and easy | Short-term, recall bias |

| Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) | Long-term habitual intake | Useful for large populations | May not capture portion sizes accurately |

| Diet History | In-depth interview | Captures long-term intake | Time-consuming |

| Food Diary (Food Record) | Self-recorded intake for 3-7 days | More accurate than recall | High participant burden |

| Weighed Food Intake | Foods weighed before eating | Highly accurate | Time-consuming, impractical |

Advantages and Disadvantages of Dietary Assessment Methods

✅ Advantages:

- Helps identify nutritional deficiencies and excesses.

- Can be used for individual and population-level assessments.

- Supports dietary intervention planning and monitoring.

❌ Disadvantages:

- Recall bias in memory-based methods.

- Time-consuming and resource-intensive for detailed methods.

- May not always reflect true dietary habits (self-reporting bias).

Difference and Comparison Between Laboratory and Biochemical Assessment

Introduction

Both laboratory assessment and biochemical assessment are used in nutritional evaluation to detect nutrient deficiencies, metabolic disorders, and chronic disease risks. While they are often used interchangeably, there are distinct differences in their focus, methodology, and applications.

Key Differences Between Laboratory and Biochemical Assessment

| Feature | Laboratory Assessment | Biochemical Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | The process of analyzing biological samples (blood, urine, stool, hair) using laboratory tests. | A specific type of laboratory assessment focusing on nutrient levels and metabolic markers. |

| Purpose | Identifies diseases, infections, organ dysfunction, and overall health status. | Assesses nutritional status, detects deficiencies, and evaluates metabolic function. |

| Scope | Broad – includes all medical laboratory tests (e.g., CBC, liver function, kidney function, infection markers). | Narrower – focuses only on nutrient-related biochemical markers. |

| Tests Included | Hematology, microbiology, immunology, toxicology, clinical chemistry. | Protein status, vitamin and mineral levels, electrolyte balance, enzyme functions. |

| Sample Used | Blood, urine, stool, saliva, tissue biopsies. | Mainly blood, urine, and hair samples. |

| Example Tests | CBC (Complete Blood Count), Blood Glucose, Liver Function Test (LFT), Kidney Function Test (KFT). | Serum Vitamin D, Serum Iron, Serum Albumin, Electrolytes (Sodium, Potassium). |

| Use in Nutrition | Identifies diseases affecting nutrition, such as infections, kidney disease, and metabolic syndrome. | Directly measures nutrients and biochemical markers related to diet. |

| Reliability | Can detect underlying diseases that affect nutrition. | More specific to nutritional status and metabolism. |

Comparison of Laboratory and Biochemical Assessment Based on Common Parameters

| Category | Laboratory Assessment | Biochemical Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Protein and Energy Status | Measures total protein and albumin to check general health. | Measures serum albumin, prealbumin, nitrogen balance, and creatinine-height index to assess malnutrition. |

| Vitamin Deficiencies | Identifies diseases caused by deficiencies but not exact levels. | Directly measures serum levels of vitamins (A, D, B12, Folate, etc.). |

| Mineral and Electrolyte Balance | Includes basic electrolyte panel (sodium, potassium, calcium, chloride, phosphorus, magnesium) to assess overall health. | Measures specific minerals related to nutrition (zinc, iron, iodine, selenium, copper, etc.). |

| Blood and Anemia Markers | Detects low hemoglobin (Hb), hematocrit (Hct), and RBC count in anemia. | Measures serum iron, ferritin, TIBC, transferrin saturation for iron deficiency diagnosis. |

| Carbohydrate Metabolism | Includes blood glucose, HbA1c for diabetes screening. | Analyzes glycemic response to diet, insulin resistance, and metabolic effects of carbohydrates. |

| Lipid Profile (Fat Metabolism) | Tests total cholesterol, LDL, HDL, triglycerides to assess heart disease risk. | Evaluates fatty acid profile, omega-3/omega-6 balance, and fat metabolism efficiency. |

| Liver and Kidney Function | Includes Liver Function Test (LFT), Kidney Function Test (KFT), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine to detect organ dysfunction. | Identifies nutritional impact on liver and kidney function (e.g., protein intake and kidney health). |

| Hormonal Influence | Measures thyroid hormones (TSH, T3, T4), adrenal hormones (cortisol, insulin, glucagon). | Identifies how nutrition affects hormone balance (e.g., iodine in thyroid function). |

| Inflammatory and Immune Markers | Includes CRP (C-Reactive Protein), WBC count to check for infection/inflammation. | Analyzes how inflammation affects nutrient absorption and metabolism. |

Advantages and Disadvantages of Each Method

| Feature | Laboratory Assessment | Biochemical Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| ✅ Advantages | Covers all medical conditions, not just nutrition-related. | Specific to nutrition, identifies deficiencies early. |

| ✅ Advantages | Can detect diseases affecting nutrient absorption (e.g., infections, liver/kidney disease). | More accurate than dietary recall methods. |

| ❌ Disadvantages | May not detect early-stage nutrient deficiencies. | Does not provide a full picture of overall health. |

| ❌ Disadvantages | More expensive and requires laboratory facilities. | Some tests are expensive and require trained personnel. |

When to Use Laboratory vs. Biochemical Assessment?

| Situation | Best Method | Why? |

|---|---|---|

| Screening for anemia | Biochemical Assessment | Measures serum iron, ferritin, transferrin saturation directly. |

| Checking for infections affecting nutrition (e.g., tuberculosis, HIV, chronic kidney disease) | Laboratory Assessment | Identifies infection, organ dysfunction, and systemic diseases. |

| Identifying protein-energy malnutrition (PEM) | Biochemical Assessment | Serum albumin, prealbumin, nitrogen balance provide more accurate results. |

| Monitoring vitamin and mineral levels | Biochemical Assessment | Directly measures serum vitamins and minerals. |

| Assessing overall health status before nutrition therapy | Laboratory Assessment | Provides a complete medical picture including kidney, liver, and immune function. |

| Diagnosing diabetes or metabolic syndrome | Both | Laboratory tests detect glucose levels, biochemical tests evaluate insulin resistance. |

Conclusion

Both laboratory assessment and biochemical assessment are essential in nutrition evaluation, but they serve different purposes:

- Laboratory assessment provides a broad health overview, including infections, organ function, and systemic diseases.

- Biochemical assessment specifically measures nutrient levels, metabolism, and deficiency risks.

Nutrition Education – Purposes

Introduction

Nutrition education is a systematic process of providing information and guidance about healthy eating, dietary habits, and nutrition-related health risks. It is designed to improve dietary behaviors, prevent malnutrition, and promote overall health and well-being.

Nutrition education is delivered at individual, community, and national levels through various strategies, including counseling, school-based programs, public health campaigns, and digital education.

Purposes of Nutrition Education

The primary purpose of nutrition education is to help individuals and communities make informed decisions about their diet and health. Below are the key purposes:

1. Promote Awareness About Healthy Eating

- Educates people about balanced diets and nutrient requirements.

- Encourages consumption of diverse and nutrient-rich foods.

- Spreads knowledge about portion sizes, meal timing, and food groups.

- Helps individuals understand nutritional labels and food safety.

✅ Example: Teaching school children about MyPlate (USA) or Food Pyramid (India) to promote healthy eating habits.

2. Prevent and Reduce Malnutrition

- Addresses undernutrition (malnutrition, stunting, wasting) and overnutrition (obesity, metabolic diseases).

- Educates vulnerable groups like pregnant women, lactating mothers, children, and elderly individuals about nutrient-rich diets.

- Encourages fortification of food (e.g., iodized salt, fortified wheat flour, vitamin D-fortified milk).

✅ Example: Government nutrition programs like POSHAN Abhiyaan (India) aim to reduce malnutrition through education and food supplementation.

3. Prevent and Manage Lifestyle-Related Diseases

- Helps control diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, obesity, and osteoporosis.

- Teaches the impact of high sugar, salt, and fat consumption on chronic diseases.

- Encourages physical activity along with healthy eating to reduce disease risk.

✅ Example: Educating diabetic patients on low glycemic index foods to manage blood sugar levels.

4. Improve Maternal and Child Health

- Ensures proper nutrition during pregnancy and lactation to prevent low birth weight and developmental issues.

- Promotes exclusive breastfeeding for at least six months.

- Guides complementary feeding practices after six months of age.

✅ Example: WHO recommends Iron-Folic Acid (IFA) supplementation during pregnancy to prevent anemia.

5. Encourage Safe Food Practices and Hygiene

- Prevents foodborne illnesses through awareness of proper food handling, cooking, and storage.

- Educates about handwashing, contamination risks, and safe drinking water.

- Highlights the dangers of processed and contaminated foods.

✅ Example: Campaigns promoting handwashing before meals and cooking food at the right temperature.

6. Address Food Security and Sustainable Eating

- Raises awareness about food availability, accessibility, and affordability.

- Promotes local, seasonal, and sustainable food choices.

- Encourages reducing food waste and consuming eco-friendly foods.

✅ Example: Teaching communities about kitchen gardening to improve access to fresh vegetables.

7. Influence Policy and Public Health Programs

- Supports government policies on school nutrition, food labeling, and fortification.

- Guides policymakers to create effective nutrition programs and dietary guidelines.

- Helps in developing national food security strategies.

✅ Example: Mandatory trans-fat labeling on packaged foods to reduce heart disease risk.

8. Promote Cultural and Traditional Dietary Knowledge

- Preserves healthy traditional food practices that align with modern nutrition science.

- Encourages consumption of locally available, affordable, and nutrient-dense foods.

✅ Example: Promoting millets (nutrient-rich grains) in India as a healthier alternative to refined cereals.

9. Improve Dietary Habits in Special Groups

- Tailors nutrition education to specific needs of athletes, elderly, vegetarians, and individuals with allergies.

- Provides therapeutic diets for renal failure, liver disease, and gastrointestinal disorders.

✅ Example: Educating lactose-intolerant individuals about alternative calcium sources like leafy greens and fortified soy milk.

10. Encourage Healthy Eating in Schools and Workplaces

- Implements school-based nutrition programs to instill healthy eating habits from an early age.

- Encourages workplace wellness programs to improve employee health and productivity.

✅ Example: Mid-Day Meal Program in India provides nutritious meals to school children to improve learning and health.

How is Nutrition Education Delivered?

| Method | Target Audience | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Individual Counseling | Patients, families | Dietitian-guided weight loss plans |

| Group Education Sessions | Schools, workplaces | Healthy cooking workshops |

| Mass Media Campaigns | General public | Advertisements on reducing sugar intake |

| Digital and Mobile Apps | Tech-savvy users | Health tracking apps like MyFitnessPal |

| Government Nutrition Programs | Communities, vulnerable groups | ICDS (India), WIC (USA) |

| Social Media Awareness | Youth, professionals | Nutrition blogs, YouTube videos |

Advantages of Nutrition Education

✅ Improves dietary habits and overall health.

✅ Prevents malnutrition and diet-related diseases.

✅ Empowers individuals to make informed food choices.

✅ Reduces healthcare costs by preventing chronic diseases.

✅ Enhances productivity in schools and workplaces.

Principles of Nutrition Education

Introduction

Nutrition education is a structured process aimed at promoting healthy eating habits, preventing nutrition-related diseases, and improving overall well-being. Effective nutrition education should be scientifically accurate, culturally relevant, and practical for implementation.

The principles of nutrition education ensure that the information provided is clear, effective, and behaviorally impactful for individuals and communities.

Key Principles of Nutrition Education

1. Scientific Accuracy and Evidence-Based Approach

- Nutrition education should be based on reliable scientific research and validated dietary guidelines.

- Information must be updated regularly to align with the latest findings in nutrition science.

- Avoids misinformation and fad diets that can lead to nutritional imbalances.

✅ Example: Using WHO dietary guidelines or National Institute of Nutrition (NIN) recommendations to guide diet planning.

2. Cultural Relevance and Acceptability

- Nutrition education must respect cultural food practices, traditions, and preferences.

- Encourages healthy modifications within traditional diets rather than imposing foreign dietary patterns.

- Should consider religious beliefs regarding food (e.g., vegetarian diets in Hinduism, halal diets in Islam).

✅ Example: Instead of recommending whole wheat bread in rural India, promoting millet-based rotis (bajra, jowar, ragi) as a nutritious alternative.

3. Simplicity and Clarity

- Information should be easily understandable and free from complex scientific jargon.

- Visual aids such as infographics, food models, and simple charts can enhance comprehension.

- Messages should be short, precise, and easy to remember.

✅ Example: Using MyPlate (USA) or Food Pyramid (India) to visually explain balanced diets.

4. Practicality and Feasibility

- Recommendations should be practical and affordable for the target audience.

- Encourages using locally available foods rather than expensive imported alternatives.

- Avoids extreme dietary restrictions that may be difficult to maintain.

✅ Example: Instead of recommending expensive protein supplements, encouraging locally available plant-based proteins like lentils, chickpeas, and soybeans.

5. Behavioral Approach for Long-Term Impact

- Nutrition education should encourage behavior change rather than just providing knowledge.

- Uses motivational strategies like goal setting, self-monitoring, and gradual habit changes.

- Focuses on realistic and achievable lifestyle modifications rather than extreme dieting.

✅ Example: Instead of saying, “Stop eating sugar completely,” suggesting, “Reduce sugar in tea gradually over a month.”

6. Lifespan and Individual Needs Approach

- Nutrition education should be tailored to different age groups and life stages.

- Special considerations for pregnant women, children, elderly individuals, and people with medical conditions.

✅ Example:

- Infants and young children → Breastfeeding and complementary feeding.

- Adolescents → Growth-boosting foods and avoiding junk food.

- Pregnant women → Folic acid, iron-rich foods, and hydration.

- Elderly → Soft-textured, easy-to-digest, and nutrient-dense foods.

7. Use of Interactive and Participatory Learning

- Engages individuals through group discussions, cooking demonstrations, role-playing, and hands-on activities.

- Encourages active participation and self-reflection rather than passive learning.

✅ Example: Instead of lecturing about food groups, organizing a practical meal-planning session where participants create a balanced meal plan.

8. Multisectoral Approach (Involvement of Various Sectors)

- Collaboration between healthcare providers, schools, government agencies, and food industries is necessary.

- Public policies, school programs, and media campaigns should align with nutrition education goals.

✅ Example:

- Schools implementing nutrition lessons in the curriculum.

- Hospitals providing dietary counseling for patients.

- Government promoting fortified foods through public programs.

9. Sustainable and Environmentally Friendly Nutrition

- Encourages sustainable eating practices that support both health and the environment.

- Reduces food waste, promotes plant-based diets, and encourages sustainable agriculture.

✅ Example:

- Promoting plant-based protein sources like lentils instead of excessive meat consumption.

- Encouraging seasonal and locally available foods instead of processed and imported foods.

10. Continuous Evaluation and Adaptation

- Nutrition education programs should be monitored and evaluated regularly to assess effectiveness.

- Modifications should be made based on feedback, changing dietary trends, and new scientific discoveries.

✅ Example:

- If a community-based nutrition program is not improving dietary habits, the teaching methods should be revised to make them more engaging and practical.

Comparison of Effective vs. Ineffective Nutrition Education

| Effective Nutrition Education | Ineffective Nutrition Education |

|---|---|

| Evidence-based and scientifically accurate | Based on myths and unverified sources |

| Culturally relevant and practical | Ignores traditional diets and local food availability |

| Uses interactive, participatory methods | Relies only on passive lectures |

| Encourages gradual behavior change | Promotes extreme or unrealistic diets |

| Involves various sectors (schools, healthcare, government) | Limited to one sector, reducing impact |

| Focuses on sustainability and food security | Does not consider environmental impact |

Methods of Nutrition Education.

Introduction

Nutrition education aims to promote healthy eating habits, prevent malnutrition, and improve overall well-being. To achieve these goals, various teaching methods and strategies are used based on the target audience, learning environment, and resources available.

Effective nutrition education methods should be interactive, evidence-based, culturally appropriate, and behaviorally impactful.

Major Methods of Nutrition Education

The methods of nutrition education can be broadly classified into:

- Individual-Based Methods

- Group-Based Methods

- Mass Media and Digital Methods

- Community-Based Methods

- School and Workplace Nutrition Education

1. Individual-Based Methods

These methods focus on one-on-one interactions, offering personalized nutrition education based on an individual’s needs.

A. Nutrition Counseling

✅ Description:

- A face-to-face session between a nutritionist/dietitian and an individual.

- Includes diet planning, behavior change techniques, and goal setting.

✅ Target Audience:

- Patients with diabetes, obesity, hypertension, anemia, malnutrition.

- Pregnant women, lactating mothers, athletes, and elderly individuals.

✅ Example:

- A diabetic patient receives counseling on how to manage blood sugar through diet.

✅ Advantages:

- Personalized and tailored to individual needs.

- More effective in achieving long-term dietary changes.

❌ Disadvantages:

- Time-consuming and requires trained professionals.

- Limited reach (only one person at a time).

B. Home Visits

✅ Description:

- A health worker visits families to educate them about nutrition and meal preparation.

- Used in rural and low-income communities to provide direct guidance.

✅ Example:

- A community health nurse visits a family to demonstrate how to prepare a nutritious meal using local ingredients.

✅ Advantages:

- Hands-on learning with real-life examples.

- Addresses family-specific dietary challenges.

❌ Disadvantages:

- Time-intensive and requires manpower.

- Limited to small-scale implementation.

2. Group-Based Methods

These methods involve teaching multiple people at once, allowing interactive learning and discussion.

A. Group Discussions and Workshops

✅ Description:

- Small group sessions where participants discuss nutrition topics and share experiences.

- Workshops may include cooking demonstrations, label reading, and meal planning exercises.

✅ Target Audience:

- School children, pregnant women, mothers, elderly groups, corporate employees.

✅ Example:

- A maternal health workshop teaches pregnant women about the importance of iron and folic acid.

✅ Advantages:

- Encourages active participation and peer learning.

- Cost-effective for educating multiple people at once.

❌ Disadvantages:

- Difficult to address individual-specific needs.

- May require trained facilitators.

B. Cooking Demonstrations

✅ Description:

- Practical, hands-on sessions that teach healthy cooking techniques and meal preparation.

- Focuses on affordable, nutritious, and culturally appropriate meals.

✅ Target Audience:

- Households, school children, community groups, hospital patients.

✅ Example:

- A nutritionist demonstrates how to cook low-sodium meals for hypertension patients.

✅ Advantages:

- Visual and practical learning enhances retention.

- Builds confidence in preparing healthy meals.

❌ Disadvantages:

- Requires kitchen facilities and ingredients.

- May be expensive and time-consuming.

C. Role Play and Storytelling

✅ Description:

- Uses drama, role-playing, or storytelling to teach nutrition concepts.

- Engages children and illiterate individuals effectively.

✅ Example:

- A theater group performs a skit on the dangers of excessive junk food consumption.

✅ Advantages:

- Memorable and engaging learning experience.

- Best for audiences with low literacy levels.

❌ Disadvantages:

- Requires creativity and trained facilitators.

3. Mass Media and Digital Methods

These methods reach large audiences and provide widespread nutrition education.

A. Television, Radio, and Print Media

✅ Description:

- Broadcasting nutrition messages through TV shows, radio programs, and newspapers.

- Used for public health campaigns.

✅ Example:

- Government campaigns promoting iodized salt and fortified foods.

✅ Advantages:

- Reaches a vast audience quickly.

- Effective in raising awareness.

❌ Disadvantages:

- One-way communication (no direct interaction).

- Difficult to measure behavior change.

B. Digital Nutrition Education (Mobile Apps, Websites, Social Media)

✅ Description:

- Smartphone apps, YouTube videos, blogs, and online courses provide digital nutrition education.

- AI-powered diet tracking apps suggest meal plans.

✅ Example:

- Apps like MyFitnessPal, HealthifyMe, and WHO Nutrition Tracker help monitor food intake.

✅ Advantages:

- Accessible anytime and anywhere.

- Cost-effective and scalable.

❌ Disadvantages:

- Limited access for rural populations without internet.

- Risk of misinformation from unreliable sources.

4. Community-Based Methods

These methods focus on improving the nutrition of an entire community.

A. Public Health Campaigns

✅ Description:

- Large-scale initiatives promoting nutrition awareness (e.g., posters, billboards, community meetings).

✅ Example:

- POSHAN Abhiyaan (India) aims to reduce malnutrition through community-based interventions.

✅ Advantages:

- Impacts a large population.

- Supports policy changes.

❌ Disadvantages:

- Requires government or organizational funding.

B. Food Fortification and Supplementation Programs

✅ Description:

- Educating people about fortified foods (e.g., iodized salt, vitamin D milk, iron-fortified cereals).

✅ Example:

- The Iron-Folic Acid Supplementation (IFA) program provides iron tablets to pregnant women.

✅ Advantages:

- Addresses widespread nutrient deficiencies effectively.

❌ Disadvantages:

- Implementation challenges in rural areas.

5. School and Workplace Nutrition Education

✅ Description:

- Incorporating nutrition education into school curriculums and employee wellness programs.

✅ Example:

- School-based nutrition programs like the Mid-Day Meal Scheme in India.

- Workplace wellness programs encouraging healthy eating habits.

✅ Advantages:

- Encourages lifelong healthy eating habits.

❌ Disadvantages:

- Effectiveness depends on curriculum integration and employer support.

Comparison of Nutrition Education Methods

| Method | Target Audience | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Counseling | Patients, high-risk individuals | Personalized, behavior-focused | Time-consuming, expensive |

| Group Discussions | Schools, workplaces, communities | Interactive, cost-effective | Less individualized |

| Mass Media Campaigns | General public | Wide reach, low cost | One-way communication |

| Digital Apps | Tech-savvy individuals | Convenient, scalable | Digital divide (not accessible to all) |

| Public Health Programs | Communities, low-income groups | Large-scale impact | Requires funding |

| Cooking Demonstrations | Households, community groups | Hands-on learning | Requires resources |