BIOCHEMISTRY UNIT 1 BSC

UNIT 1 CARBOHYDRATES

Introduction to Carbohydrates in Biochemistry

Carbohydrates are one of the four primary classes of biomolecules, which also include proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids. They play a crucial role in the structure and function of living organisms. Carbohydrates are organic compounds made up of carbon (C), hydrogen (H), and oxygen (O) atoms, typically with a hydrogen to oxygen atom ratio of 2:1, as in water (H₂O). Their general formula is (CH2O)n(CH_2O)_n(CH2O)n, where nnn is the number of carbon atoms.

Classification of Carbohydrates

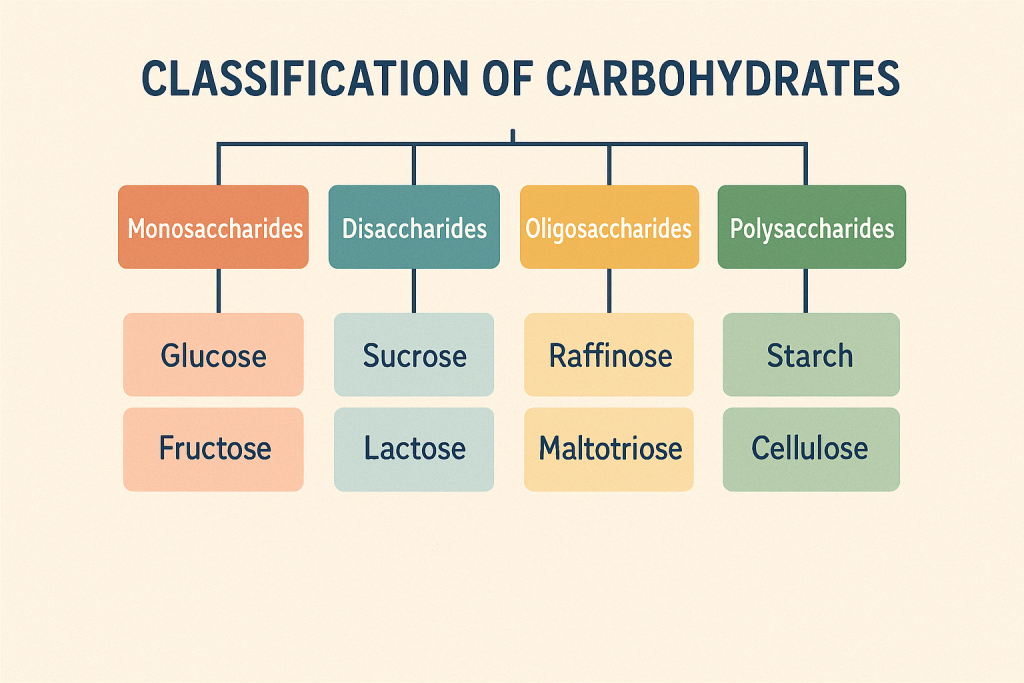

Carbohydrates are classified based on the number of sugar units:

- Monosaccharides: These are the simplest form of carbohydrates, consisting of a single sugar unit. Examples include glucose, fructose, and galactose. They are the building blocks for more complex carbohydrates.

- Disaccharides: These consist of two monosaccharide units linked together by a glycosidic bond. Common disaccharides include sucrose (table sugar), lactose (milk sugar), and maltose.

- Oligosaccharides: Comprising 3 to 10 monosaccharide units, oligosaccharides are found attached to proteins and lipids on cell surfaces and play a role in cell recognition and signaling.

- Polysaccharides: These are large molecules made up of more than ten monosaccharide units. Examples include starch, glycogen, and cellulose. Polysaccharides serve as energy storage (like starch in plants and glycogen in animals) and structural components (like cellulose in the plant cell wall).

Functions of Carbohydrates

- Energy Source: Carbohydrates are the body’s primary source of energy. Glucose, a monosaccharide, is the most important carbohydrate for cellular energy. It is metabolized during cellular respiration to produce ATP, the energy currency of cells.

- Energy Storage: Polysaccharides like starch and glycogen serve as energy reserves. Glycogen is stored in the liver and muscles and can be rapidly mobilized to meet energy demands.

- Structural Role: Carbohydrates like cellulose provide structural integrity to plants. In animals, carbohydrates are found in extracellular matrices and on the surfaces of cells, where they contribute to cellular architecture.

- Cell Recognition and Signaling: Oligosaccharides attached to proteins and lipids on cell surfaces are involved in cell recognition processes, such as blood group typing and immune responses.

- Sparing Protein and Fat: When adequate carbohydrates are available in the diet, proteins and fats are spared from being used as energy sources. This allows proteins to perform their vital functions in tissue repair and enzyme activity, while fats are used for long-term energy storage and insulation.

Importance in Biochemistry

In biochemistry, carbohydrates are essential for understanding metabolism, energy production, and storage. The study of carbohydrate metabolism includes processes like glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, and the citric acid cycle, which are central to energy production in cells. Carbohydrates also play a key role in the structure of nucleotides and nucleic acids, which are crucial for genetic information storage and transmission.

Overall, carbohydrates are indispensable for life, providing energy, structural components, and key functions in cell signaling and molecular recognition. Their study is fundamental in biochemistry, offering insights into health, disease, and the molecular mechanisms of life.

Digestion, Absorption, and Metabolism of Carbohydrates

1. Digestion of Carbohydrates

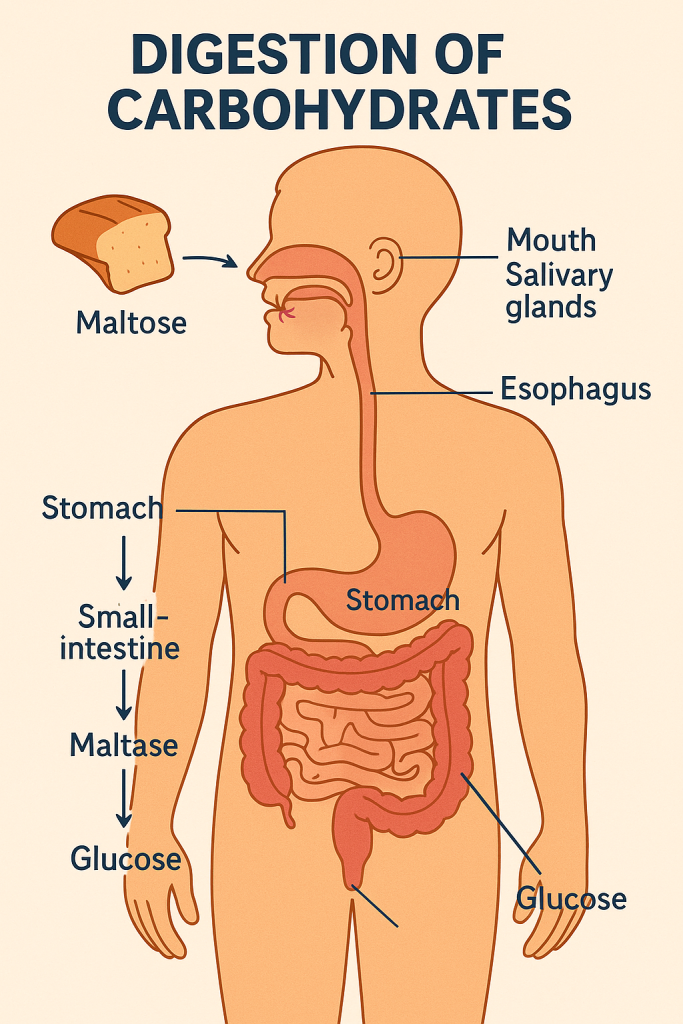

The digestion of carbohydrates begins in the mouth and continues through the gastrointestinal tract, involving both mechanical and chemical processes to break down complex carbohydrates into absorbable monosaccharides.

- Mouth: The process starts in the mouth, where the enzyme salivary amylase (ptyalin) begins breaking down starch (a polysaccharide) into smaller chains of glucose molecules called dextrins and maltose. Chewing also physically breaks down food, increasing its surface area for enzymatic action.

- Stomach: The acidic environment of the stomach inactivates salivary amylase, halting the digestion of carbohydrates. However, the stomach’s mechanical actions continue to mix the food, creating a semi-liquid mixture called chyme.

- Small Intestine: The majority of carbohydrate digestion occurs in the small intestine. Pancreatic amylase is secreted into the small intestine and continues breaking down dextrins into disaccharides like maltose. The brush border enzymes of the small intestine, including maltase, sucrase, and lactase, then break down these disaccharides into monosaccharides (glucose, fructose, and galactose).

2. Absorption of Carbohydrates

- Small Intestine: Monosaccharides are absorbed by the enterocytes (intestinal cells) in the small intestine. Glucose and galactose are absorbed via active transport through the sodium-glucose linked transporter 1 (SGLT1), while fructose is absorbed via facilitated diffusion through the GLUT5 transporter.

- Bloodstream: Once inside the enterocytes, these monosaccharides are transported into the bloodstream via the GLUT2 transporter. They are then carried to the liver through the portal vein.

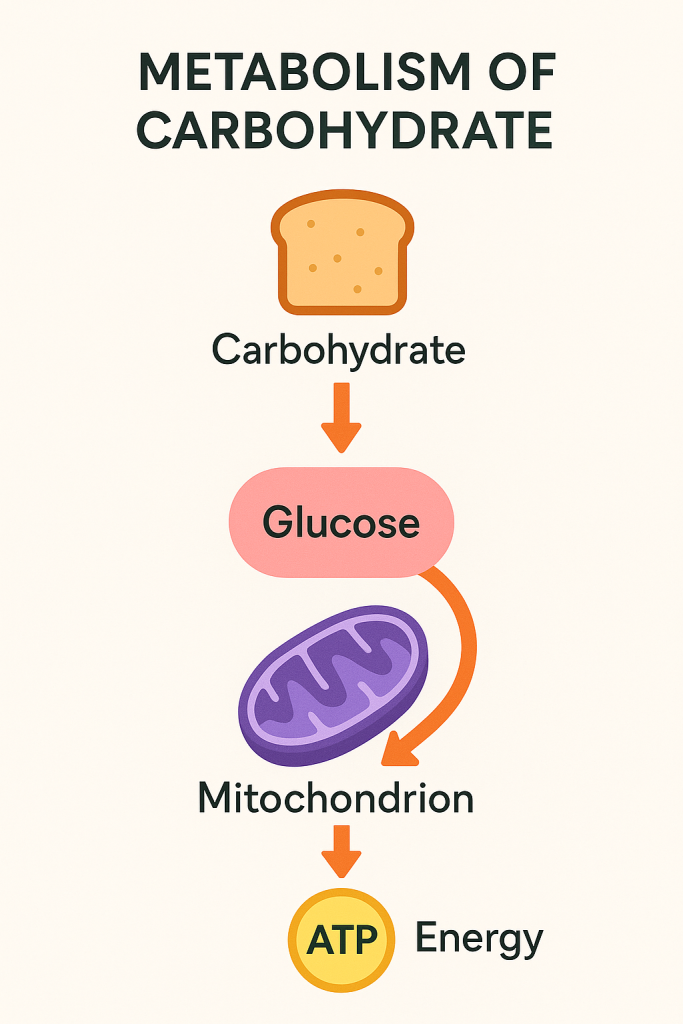

3. Metabolism of Carbohydrates

After absorption, carbohydrates are metabolized to produce energy, store energy, or form other molecules required by the body.

- Glycolysis: In the cytoplasm of cells, glucose undergoes glycolysis, a series of reactions that convert glucose into pyruvate, generating a small amount of ATP (energy) and NADH in the process. Glycolysis does not require oxygen and occurs in both aerobic and anaerobic conditions.

- Pyruvate Metabolism: In the presence of oxygen, pyruvate is transported into the mitochondria, where it is converted into acetyl-CoA, entering the citric acid cycle (Krebs cycle). This cycle produces more NADH and FADH2, which are used in the electron transport chain to generate a large amount of ATP through oxidative phosphorylation.

- Citric Acid Cycle: The citric acid cycle occurs in the mitochondria and involves the complete oxidation of acetyl-CoA, producing carbon dioxide, ATP, NADH, and FADH2. The high-energy electrons from NADH and FADH2 are then transferred to the electron transport chain to produce more ATP.

- Gluconeogenesis: When glucose levels are low, the liver can produce glucose from non-carbohydrate precursors like lactate, glycerol, and amino acids through gluconeogenesis. This process ensures a steady supply of glucose for tissues that depend on it, like the brain and red blood cells.

- Glycogenesis and Glycogenolysis: Excess glucose is stored as glycogen in the liver and muscles (glycogenesis). When energy is needed, glycogen is broken down into glucose-1-phosphate and then into glucose-6-phosphate, which enters glycolysis (glycogenolysis).

- Pentose Phosphate Pathway: Some glucose is diverted into the pentose phosphate pathway, which produces NADPH (used in biosynthetic reactions and antioxidant defense) and ribose-5-phosphate (used in nucleotide synthesis).

- Storage as Fat: When glycogen stores are full, excess glucose is converted into fatty acids through lipogenesis and stored as fat in adipose tissue.

4. Regulation of Carbohydrate Metabolism

Carbohydrate metabolism is tightly regulated by hormones to maintain blood glucose levels within a narrow range:

- Insulin: Secreted by the pancreas in response to high blood glucose levels, insulin promotes the uptake of glucose by cells and stimulates glycogenesis, glycolysis, and lipogenesis, while inhibiting gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis.

- Glucagon: Also secreted by the pancreas, but in response to low blood glucose levels, glucagon stimulates glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis, raising blood glucose levels.

- Epinephrine and Cortisol: These stress hormones also play roles in increasing blood glucose levels by stimulating glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis.

Carbohydrates undergo a complex process of digestion, absorption, and metabolism to provide energy, maintain blood glucose levels, and serve as building blocks for other essential molecules. This intricate balance is crucial for normal physiological function and overall health.

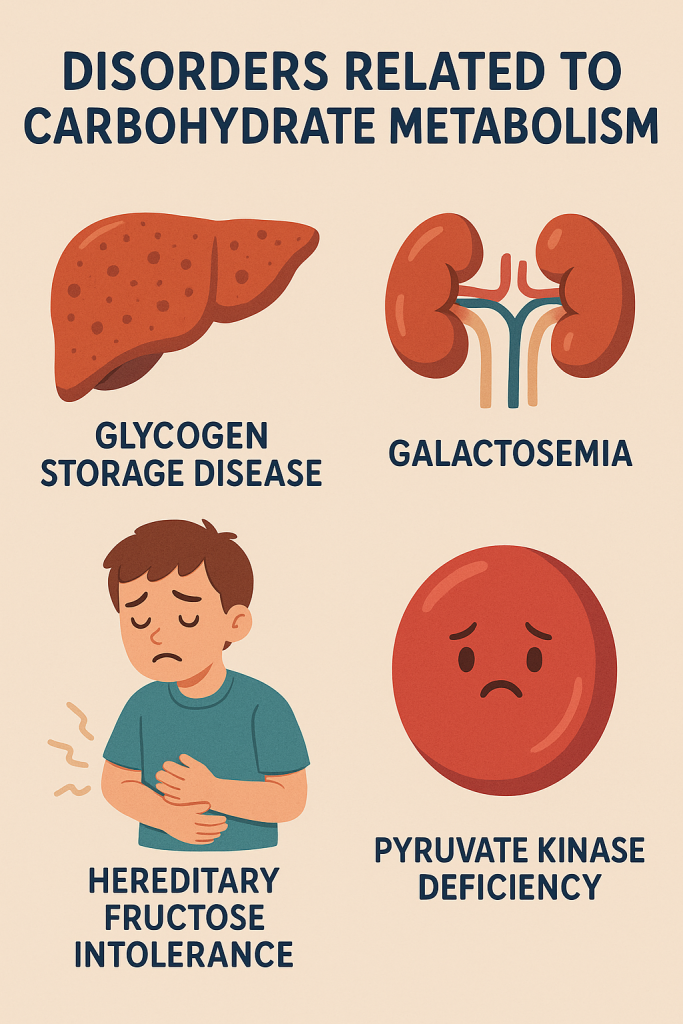

Disorders Related to Carbohydrate Metabolism

Carbohydrate metabolism disorders are conditions that affect the body’s ability to process and utilize carbohydrates, leading to various health issues. These disorders can result from genetic mutations, enzyme deficiencies, hormonal imbalances, or other factors that disrupt normal metabolic pathways. Below are some of the key disorders related to carbohydrate metabolism:

1. Diabetes Mellitus

- Type 1 Diabetes: An autoimmune condition where the body’s immune system attacks and destroys insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas. This leads to a lack of insulin, causing elevated blood glucose levels (hyperglycemia).

- Type 2 Diabetes: A metabolic disorder characterized by insulin resistance, where the body’s cells do not respond properly to insulin, and relative insulin deficiency. This is often associated with obesity, sedentary lifestyle, and genetic predisposition.

- Gestational Diabetes: A form of diabetes that develops during pregnancy due to hormonal changes, which can affect how the body uses insulin.

2. Glycogen Storage Diseases (GSD)

- Von Gierke’s Disease (GSD Type I): Caused by a deficiency of glucose-6-phosphatase, an enzyme that converts glycogen to glucose. This results in the accumulation of glycogen in the liver and kidneys, leading to hypoglycemia and enlargement of the liver (hepatomegaly).

- Pompe Disease (GSD Type II): Caused by a deficiency of acid alpha-glucosidase, an enzyme that breaks down glycogen in lysosomes. This leads to the accumulation of glycogen in various tissues, particularly muscles, causing muscle weakness and heart problems.

- Cori Disease (GSD Type III): Resulting from a deficiency of the debranching enzyme, leading to the accumulation of abnormal glycogen with short outer branches. This causes hypoglycemia, muscle weakness, and liver enlargement.

3. Galactosemia

- An inherited disorder caused by a deficiency of one of the enzymes needed to convert galactose (a sugar found in milk) into glucose. The most common form is due to a deficiency of the enzyme galactose-1-phosphate uridyltransferase (GALT). Accumulation of galactose or its metabolites can cause liver damage, intellectual disability, cataracts, and kidney problems.

4. Hereditary Fructose Intolerance (HFI)

- A genetic condition caused by a deficiency of the enzyme aldolase B, which is necessary for the metabolism of fructose. Ingesting fructose, sucrose, or sorbitol can lead to severe hypoglycemia, abdominal pain, vomiting, and liver damage due to the accumulation of toxic metabolites.

5. Lactose Intolerance

- A common condition where the body lacks the enzyme lactase, which is needed to digest lactose, the sugar found in milk and dairy products. This leads to symptoms like bloating, diarrhea, and abdominal pain after consuming dairy products.

6. Fructose Malabsorption

- A condition where the small intestine cannot properly absorb fructose. This leads to fructose being fermented by bacteria in the colon, causing symptoms like bloating, diarrhea, and abdominal discomfort.

7. Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Complex Deficiency

- A rare genetic disorder where there is a deficiency in the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, an enzyme complex that plays a crucial role in converting pyruvate to acetyl-CoA for entry into the citric acid cycle. This deficiency leads to lactic acidosis, neurological defects, and developmental delays.

8. Maturity Onset Diabetes of the Young (MODY)

- A group of monogenic forms of diabetes caused by mutations in genes involved in beta-cell function. MODY is characterized by non-insulin-dependent diabetes that usually develops before the age of 25. It has features that overlap with both Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes but is genetically distinct.

9. Hyperinsulinism

- A condition characterized by excessive secretion of insulin, leading to hypoglycemia. It can be congenital (persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy) or acquired, often due to insulin-secreting tumors (insulinomas).

10. Maple Syrup Urine Disease (MSUD)

- Although primarily a disorder of amino acid metabolism, MSUD can also affect carbohydrate metabolism due to the close relationship between the metabolism of branched-chain amino acids and glucose. This condition leads to the accumulation of branched-chain amino acids and their toxic by-products, causing a sweet-smelling urine, neurological damage, and other severe symptoms.

Disorders related to carbohydrate metabolism can have a wide range of effects on the body, from mild to life-threatening. Early diagnosis and management are crucial for preventing complications and improving quality of life. Treatment may involve dietary changes, enzyme replacement therapies, or other medical interventions tailored to the specific disorder. Understanding these metabolic conditions is essential for effective management and prevention of related health issues.

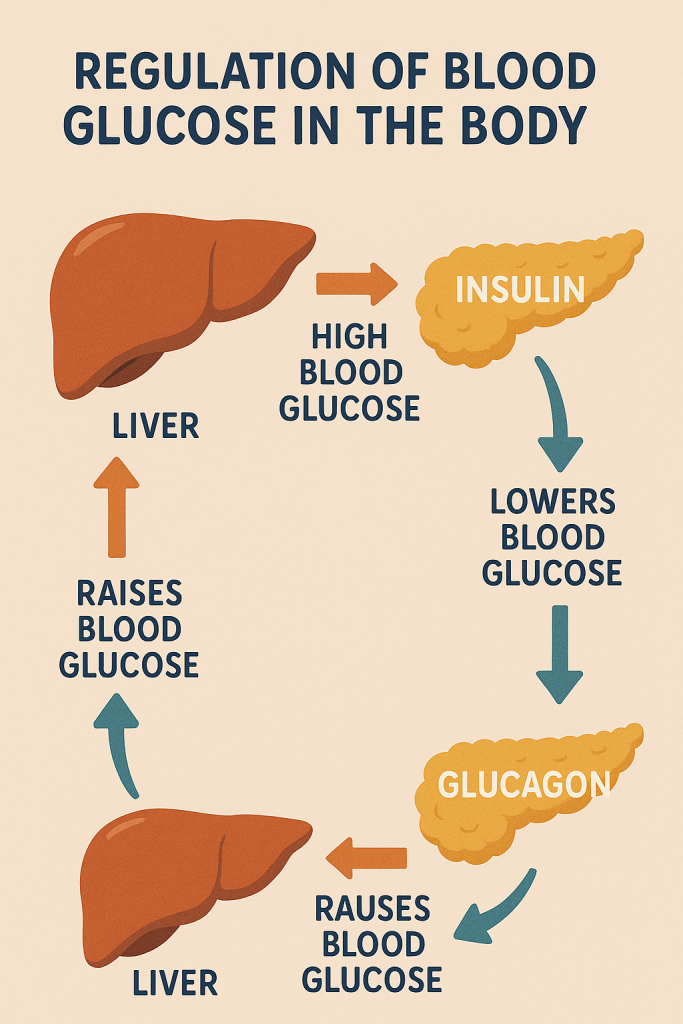

Regulation of Blood Glucose in the Body

The regulation of blood glucose levels is a vital physiological process that ensures a steady supply of glucose, the primary energy source for the body’s cells, especially the brain and red blood cells. This regulation is tightly controlled by a balance between glucose production, storage, and utilization, primarily involving the liver, pancreas, and various hormones. The body maintains blood glucose levels within a narrow range (about 70-100 mg/dL fasting levels) through several mechanisms:

1. Hormonal Regulation

The two primary hormones involved in blood glucose regulation are insulin and glucagon, both produced by the pancreas:

- Insulin: Produced by the beta cells of the pancreas in response to high blood glucose levels (e.g., after eating), insulin lowers blood glucose by:

- Promoting the uptake of glucose by muscle and fat cells through GLUT4 transporters.

- Stimulating the liver to convert glucose into glycogen for storage (glycogenesis).

- Inhibiting gluconeogenesis (the production of glucose from non-carbohydrate sources) and glycogenolysis (the breakdown of glycogen into glucose).

- Enhancing lipogenesis (fat storage) and inhibiting lipolysis (fat breakdown).

- Glucagon: Produced by the alpha cells of the pancreas when blood glucose levels are low (e.g., during fasting), glucagon raises blood glucose by:

- Stimulating glycogenolysis in the liver, releasing glucose into the bloodstream.

- Promoting gluconeogenesis in the liver.

- Inhibiting glycogenesis (the synthesis of glycogen) and enhancing the release of glucose from the liver into the blood.

Other hormones involved in blood glucose regulation include:

- Epinephrine (Adrenaline): Released by the adrenal glands during stress or exercise, it stimulates glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis, increasing blood glucose levels to provide energy for the “fight or flight” response.

- Cortisol: A steroid hormone released by the adrenal glands in response to stress, it increases blood glucose by stimulating gluconeogenesis and reducing the uptake of glucose by tissues other than the brain.

- Growth Hormone: Secreted by the pituitary gland, it increases blood glucose by reducing the uptake of glucose by tissues and promoting gluconeogenesis in the liver.

2. Metabolic Pathways Involved

- Glycogenesis: The process of converting glucose into glycogen for storage in the liver and muscles. This occurs when blood glucose levels are high, under the influence of insulin.

- Glycogenolysis: The breakdown of glycogen into glucose, primarily in the liver, to maintain blood glucose levels during fasting or between meals. This process is stimulated by glucagon and epinephrine.

- Gluconeogenesis: The production of glucose from non-carbohydrate sources, such as amino acids and glycerol, in the liver. This pathway becomes critical during prolonged fasting or intense exercise, and it is stimulated by glucagon, cortisol, and epinephrine.

- Glycolysis: The breakdown of glucose to pyruvate, generating ATP. Glycolysis occurs in all cells and provides energy, particularly when insulin levels are high.

- Lipogenesis: The process of converting excess glucose into fatty acids, which are then stored as triglycerides in adipose tissue. Insulin promotes lipogenesis when there is an excess of glucose.

- Lipolysis: The breakdown of triglycerides into fatty acids and glycerol, which can be used as an alternative energy source when glucose is scarce. This process is inhibited by insulin and promoted by glucagon and epinephrine.

3. Liver’s Role in Glucose Regulation

The liver plays a central role in maintaining blood glucose levels. It acts as a glucose buffer by storing glucose as glycogen after meals (under the influence of insulin) and releasing glucose during fasting or stress (under the influence of glucagon and other hormones). The liver also carries out gluconeogenesis, providing a continuous supply of glucose even in the absence of dietary intake.

4. Role of Muscle and Adipose Tissue

- Muscle Tissue: Muscle cells take up glucose from the blood in response to insulin and store it as glycogen. During exercise or fasting, muscle glycogen can be broken down to provide energy, though this glucose is primarily used within the muscle cells themselves.

- Adipose Tissue: Fat cells also take up glucose in response to insulin, converting it to triglycerides for long-term energy storage. During fasting or when insulin levels are low, adipose tissue breaks down triglycerides into free fatty acids and glycerol, which can be used as alternative energy sources by other tissues.

5. Feedback Mechanisms

The regulation of blood glucose is governed by feedback mechanisms that maintain homeostasis:

- Negative Feedback: When blood glucose levels rise after eating, insulin is released, promoting glucose uptake and storage, thereby lowering blood glucose levels. When glucose levels drop, glucagon is released, raising blood glucose by promoting glycogen breakdown and gluconeogenesis.

- Positive Feedback (in certain conditions): In cases like stress or intense exercise, hormones like epinephrine and cortisol amplify the release of glucose into the bloodstream, ensuring that the body has enough energy to respond to the situation.

The regulation of blood glucose is a complex, tightly controlled process involving multiple hormones, organs, and metabolic pathways. Maintaining proper blood glucose levels is essential for energy production, metabolic function, and overall health. Dysregulation of this system can lead to metabolic disorders like diabetes mellitus, highlighting the importance of these regulatory mechanisms.

Diabetes Mellitus: Type 1 and Type 2

Diabetes Mellitus is a group of metabolic disorders characterized by chronic hyperglycemia (high blood glucose levels) resulting from defects in insulin secretion, insulin action, or both. It is broadly classified into two main types: Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes.

Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus (T1DM)

- Etiology: Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune condition where the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks and destroys the insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas. This leads to an absolute deficiency of insulin.

- Onset: Typically develops in childhood or adolescence, though it can occur at any age.

- Insulin Dependence: Individuals with Type 1 diabetes require lifelong insulin therapy as the body cannot produce insulin.

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM)

- Etiology: Type 2 diabetes is primarily characterized by insulin resistance, where the body’s cells do not respond effectively to insulin. This is often accompanied by a relative insulin deficiency. It is strongly associated with obesity, physical inactivity, and genetic factors.

- Onset: Usually develops in adults over 40 years of age but is increasingly seen in younger individuals, including children, due to rising obesity rates.

- Insulin Dependence: Initially, it may be managed with lifestyle changes and oral medications, but over time, insulin therapy may be required as the disease progresses.

Symptoms of Diabetes Mellitus

Both Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes share common symptoms, though they may present differently:

- Polyuria: Frequent urination due to high blood glucose levels leading to increased urine production.

- Polydipsia: Excessive thirst as a result of dehydration from polyuria.

- Polyphagia: Increased hunger because the body’s cells are unable to utilize glucose effectively.

- Unexplained Weight Loss: More common in Type 1 diabetes, due to the body breaking down fat and muscle for energy.

- Fatigue: Persistent tiredness due to the lack of glucose entering the cells.

- Blurred Vision: High blood sugar can cause the lens of the eye to swell, leading to vision changes.

- Slow Healing of Wounds: Impaired blood circulation and high blood sugar can delay the healing process.

- Frequent Infections: High glucose levels can weaken the immune system, leading to recurrent infections, particularly urinary tract infections, and skin infections.

Complications of Diabetes Mellitus

Chronic hyperglycemia can lead to both acute and long-term complications:

Acute Complications

- Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA): More common in Type 1 diabetes, DKA is a life-threatening condition where the body starts breaking down fat at a rapid rate, leading to the accumulation of ketones in the blood, causing the blood to become acidic.

- Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State (HHS): More common in Type 2 diabetes, HHS is characterized by extremely high blood glucose levels without significant ketosis, leading to severe dehydration and altered consciousness.

Long-term Complications

- Cardiovascular Disease: Increased risk of heart attacks, strokes, and peripheral artery disease due to damage to blood vessels.

- Neuropathy: Nerve damage that can lead to numbness, tingling, and pain, especially in the extremities (peripheral neuropathy), as well as digestive problems, sexual dysfunction, and other issues (autonomic neuropathy).

- Nephropathy: Kidney damage that can progress to chronic kidney disease and even kidney failure.

- Retinopathy: Damage to the blood vessels in the retina, leading to vision problems and even blindness.

- Foot Complications: Poor circulation and nerve damage can lead to foot ulcers, infections, and in severe cases, amputation.

Management of Diabetes Mellitus

Management of diabetes involves a combination of lifestyle changes, medication, and regular monitoring to maintain blood glucose levels within a target range and prevent complications.

Type 1 Diabetes Management

- Insulin Therapy: Lifelong insulin therapy is necessary, which can be administered through injections or an insulin pump. Types of insulin include rapid-acting, short-acting, intermediate-acting, and long-acting.

- Blood Glucose Monitoring: Frequent self-monitoring of blood glucose levels to adjust insulin doses and manage blood sugar.

- Dietary Management: A balanced diet that includes counting carbohydrates to match insulin doses, along with regular meals to avoid fluctuations in blood glucose levels.

- Physical Activity: Regular exercise to help control blood glucose levels, with careful monitoring to avoid hypoglycemia (low blood sugar).

Type 2 Diabetes Management

- Lifestyle Modifications:

- Diet: A healthy, balanced diet that is low in refined carbohydrates and sugars, rich in fiber, and includes portion control to manage weight.

- Exercise: Regular physical activity to improve insulin sensitivity and help with weight management.

- Weight Management: Achieving and maintaining a healthy weight is crucial in managing Type 2 diabetes.

- Oral Medications: Several classes of oral medications are available to manage blood glucose levels, including:

- Metformin: Decreases glucose production in the liver and improves insulin sensitivity.

- Sulfonylureas: Stimulate the pancreas to release more insulin.

- DPP-4 Inhibitors: Increase insulin release and decrease glucagon levels.

- SGLT2 Inhibitors: Increase glucose excretion through urine.

- Thiazolidinediones (TZDs): Improve insulin sensitivity.

- Insulin Therapy: May be required if oral medications and lifestyle changes are insufficient in controlling blood glucose levels.

- Monitoring: Regular monitoring of blood glucose levels, as well as HbA1c (a measure of average blood glucose levels over the past 2-3 months), to assess long-term glucose control.

Effective management of diabetes requires a comprehensive approach that includes lifestyle modifications, medication adherence, regular monitoring, and education. Early detection and proper management are key to preventing or delaying the onset of complications, thereby improving the quality of life for individuals with diabetes.

Investigations for Diabetes Mellitus

The diagnosis and monitoring of diabetes mellitus involve several laboratory tests and assessments to measure blood glucose levels, evaluate the function of insulin, and detect any complications associated with the disease. These investigations can be categorized into diagnostic tests, monitoring tests, and tests for complications.

1. Diagnostic Tests for Diabetes Mellitus

- Fasting Plasma Glucose (FPG) Test:

- Purpose: Measures blood glucose levels after an overnight fast (at least 8 hours without eating).

- Diagnostic Criteria:

- Normal: <100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L)

- Prediabetes: 100-125 mg/dL (5.6-6.9 mmol/L)

- Diabetes: ≥126 mg/dL (7.0 mmol/L) on two separate occasions.

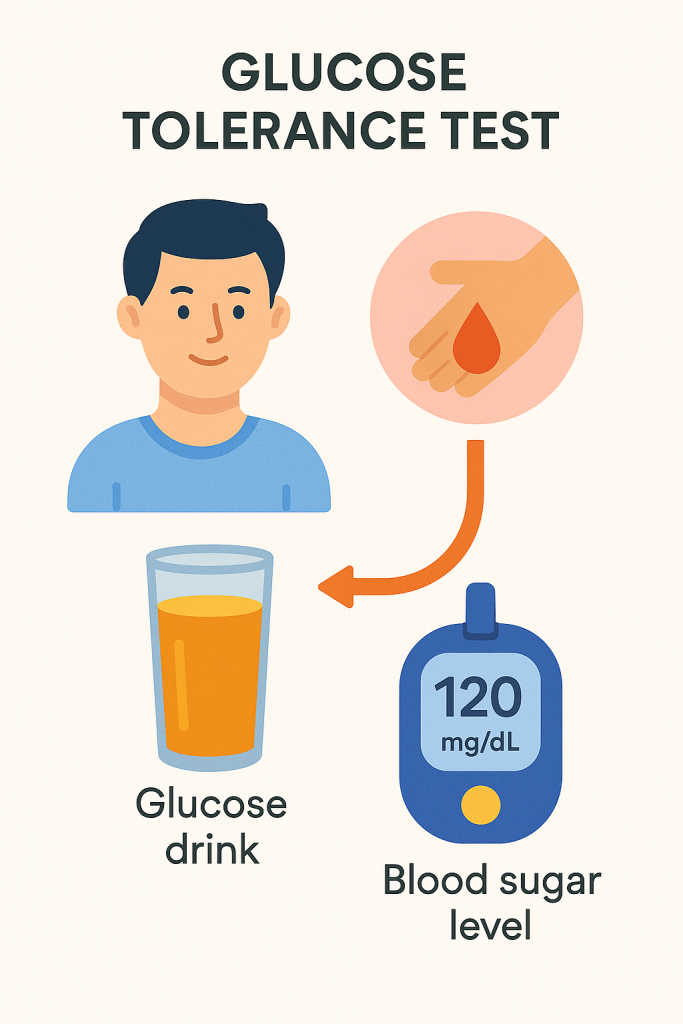

- Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT):

- Purpose: Measures blood glucose levels before and 2 hours after consuming a 75-gram glucose solution.

- Diagnostic Criteria:

- Normal: 2-hour glucose <140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L)

- Prediabetes: 2-hour glucose 140-199 mg/dL (7.8-11.0 mmol/L)

- Diabetes: 2-hour glucose ≥200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L).

- Random Plasma Glucose Test:

- Purpose: Measures blood glucose levels at any time, without fasting.

- Diagnostic Criteria: A random blood glucose level of ≥200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L) with classic symptoms of diabetes (polyuria, polydipsia, and unexplained weight loss) indicates diabetes.

- Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) Test:

- Purpose: Reflects the average blood glucose levels over the past 2-3 months by measuring the percentage of glycated hemoglobin in the blood.

- Diagnostic Criteria:

- Normal: <5.7%

- Prediabetes: 5.7%-6.4%

- Diabetes: ≥6.5%.

- C-Peptide Test:

- Purpose: Measures the level of C-peptide, which is a byproduct of insulin production. It helps to distinguish between Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes.

- Interpretation:

- Low C-peptide levels indicate Type 1 diabetes (where insulin production is low or absent).

- Normal or high C-peptide levels suggest Type 2 diabetes (where insulin production is still present but may be insufficient).

- Autoantibody Tests:

- Purpose: Detects antibodies that attack insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas, indicating an autoimmune response typical of Type 1 diabetes.

- Common Autoantibodies:

- Glutamic acid decarboxylase antibodies (GADA)

- Insulin autoantibodies (IAA)

- Islet cell antibodies (ICA)

- Insulinoma-associated-2 autoantibodies (IA-2A).

2. Monitoring Tests for Diabetes Mellitus

- Self-Monitoring of Blood Glucose (SMBG):

- Purpose: Allows individuals with diabetes to regularly check their blood glucose levels at home using a glucometer.

- Frequency: Depends on the treatment plan, typically multiple times a day for those on insulin.

- Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM):

- Purpose: Provides real-time glucose readings throughout the day and night using a sensor placed under the skin.

- Advantages: Helps in understanding glucose trends and making more informed decisions about insulin dosing and lifestyle adjustments.

- Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) Test:

- Purpose: Used for ongoing monitoring of diabetes management, reflecting long-term glucose control.

- Target Levels: For most people with diabetes, the goal is to maintain HbA1c below 7%, but individual targets may vary.

3. Tests for Complications of Diabetes Mellitus

- Urine Albumin-to-Creatinine Ratio (UACR):

- Purpose: Detects early signs of diabetic nephropathy (kidney damage) by measuring the amount of albumin (a type of protein) in the urine.

- Interpretation: An elevated UACR (>30 mg/g) indicates early kidney damage.

- Serum Creatinine and Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR):

- Purpose: Assesses kidney function by measuring creatinine levels in the blood and estimating the filtration rate of the kidneys.

- Interpretation: Decreased eGFR indicates reduced kidney function.

- Dilated Eye Exam:

- Purpose: Detects diabetic retinopathy, cataracts, and glaucoma by examining the retina and other structures of the eye.

- Frequency: Annually or as recommended by an eye specialist.

- Foot Examination:

- Purpose: Assesses the risk of diabetic foot complications by examining the skin, circulation, and sensation in the feet.

- Components: Includes checking for peripheral neuropathy (using a monofilament test), foot ulcers, and signs of poor circulation.

- Lipid Profile:

- Purpose: Measures levels of total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides to assess the risk of cardiovascular complications.

- Target Levels: Individuals with diabetes often have specific lipid targets to reduce cardiovascular risk.

- Blood Pressure Monitoring:

- Purpose: Regular monitoring of blood pressure is crucial as hypertension is a common comorbidity in diabetes and increases the risk of complications.

- Electrocardiogram (ECG):

- Purpose: Evaluates heart function and detects any abnormalities that might indicate cardiovascular disease, which is more common in individuals with diabetes.

A comprehensive set of investigations is essential for the diagnosis, monitoring, and management of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Regular monitoring and timely investigations help in optimizing treatment, preventing complications, and improving the overall quality of life for individuals with diabetes.

Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT)

The Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT) is a diagnostic tool used to evaluate the body’s ability to metabolize glucose. It is primarily used to diagnose diabetes mellitus, particularly gestational diabetes, and assess glucose tolerance in individuals with borderline fasting glucose levels.

Indications for OGTT

- Diagnosis of Prediabetes and Diabetes: OGTT is indicated when fasting plasma glucose levels are borderline or when symptoms of diabetes are present, but fasting glucose levels are not conclusive.

- Diagnosis of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM): OGTT is the standard test for diagnosing gestational diabetes during pregnancy, typically conducted between 24 and 28 weeks of gestation.

- Evaluation of Reactive Hypoglycemia: OGTT can be used to assess individuals who experience symptoms of hypoglycemia after meals.

- Assessment of Impaired Glucose Tolerance (IGT): To evaluate individuals with a family history of diabetes, obesity, or other risk factors who may be at risk of developing Type 2 diabetes.

Procedure of OGTT

- Preparation:

- The patient should be on a regular diet with adequate carbohydrates (150-200 grams per day) for at least 3 days before the test.

- The patient should fast for at least 8-10 hours before the test (water is allowed).

- The test is usually conducted in the morning to ensure consistent fasting conditions.

- Initial Fasting Blood Glucose Measurement:

- A blood sample is taken to measure the fasting plasma glucose level.

- Glucose Administration:

- The patient is given a glucose solution to drink, which contains 75 grams of glucose dissolved in 250-300 mL of water for non-pregnant adults. For pregnant women, the amount may vary depending on the test protocol.

- The glucose drink should be consumed within 5 minutes.

- Blood Glucose Measurements:

- Blood samples are taken at specific intervals after drinking the glucose solution, typically at 30 minutes, 1 hour, and 2 hours. In some cases, additional samples may be taken at 3 hours or longer.

- The timing and number of blood samples may vary depending on the protocol being followed.

- Monitoring:

- The patient should remain seated and avoid physical activity, eating, or drinking anything else during the test.

Interpretation of OGTT Results

The results of the OGTT are interpreted based on the blood glucose levels measured at fasting, 1 hour, and 2 hours post-glucose ingestion.

- Normal Glucose Tolerance:

- Fasting glucose: <100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L)

- 2-hour glucose: <140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L)

- Impaired Fasting Glucose (IFG):

- Fasting glucose: 100-125 mg/dL (5.6-6.9 mmol/L)

- Impaired Glucose Tolerance (IGT):

- 2-hour glucose: 140-199 mg/dL (7.8-11.0 mmol/L)

- Diabetes Mellitus:

- Fasting glucose: ≥126 mg/dL (7.0 mmol/L)

- 2-hour glucose: ≥200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L)

- Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM) (using a 2-hour 75-gram OGTT):

- Fasting glucose: ≥92 mg/dL (5.1 mmol/L)

- 1-hour glucose: ≥180 mg/dL (10.0 mmol/L)

- 2-hour glucose: ≥153 mg/dL (8.5 mmol/L)

Types of Glucose Tolerance Test (GTT) Curves

The glucose tolerance test curve represents the blood glucose levels plotted against time after glucose ingestion. Different patterns of GTT curves indicate various glucose tolerance statuses:

- Normal Curve:

- Pattern: A rise in blood glucose level after glucose ingestion, peaking within 30 to 60 minutes, followed by a gradual decline to near fasting levels by 2 hours.

- Indication: Normal glucose tolerance.

- Diabetic Curve:

- Pattern: A higher peak glucose level than normal, with a slower decline, resulting in elevated glucose levels even at 2 hours.

- Indication: Diabetes mellitus.

- Flat Curve:

- Pattern: Minimal rise in glucose levels after ingestion, often associated with hypoglycemia or other metabolic conditions.

- Indication: May indicate malabsorption, reactive hypoglycemia, or adrenal insufficiency.

- Lag Curve (Impaired Glucose Tolerance):

- Pattern: A delayed peak, with glucose levels rising slowly, peaking later than normal, and staying elevated at 2 hours but below the diabetic threshold.

- Indication: Impaired glucose tolerance or prediabetes.

- Hypoglycemic Curve:

- Pattern: A normal or exaggerated initial rise in glucose levels followed by a rapid drop below fasting levels, sometimes leading to symptoms of hypoglycemia.

- Indication: Reactive hypoglycemia or insulinoma.

The OGTT is a crucial tool for diagnosing and assessing glucose metabolism disorders, including diabetes mellitus and gestational diabetes. Understanding the procedure, interpretation, and the different types of GTT curves helps healthcare providers identify and manage individuals at risk of or living with diabetes and related conditions effectively.

Types of Glucose Tolerance Tests (GTT) and Related Tests

In addition to the standard Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT), several variations of glucose tolerance tests are used in specific clinical situations to diagnose and manage disorders related to glucose metabolism. These include the Mini GTT, Extended GTT, Glucose Challenge Test (GCT), and Intravenous Glucose Tolerance Test (IV GTT).

1. Mini Glucose Tolerance Test (Mini GTT)

- Purpose: The Mini GTT is a simplified version of the OGTT, often used in preliminary screenings for glucose intolerance, particularly in situations where a full OGTT may not be feasible.

- Procedure:

- The patient is given a smaller dose of glucose, typically 50 grams, instead of the standard 75 grams.

- Blood glucose levels are measured at baseline (fasting) and then at 1 hour after ingestion of the glucose solution.

- Indications:

- Preliminary screening for gestational diabetes.

- Screening in populations where full OGTT may not be practical or necessary.

- Interpretation:

- If the 1-hour glucose level is elevated (≥140 mg/dL or 7.8 mmol/L), a full OGTT may be recommended for further assessment.

2. Extended Glucose Tolerance Test (Extended GTT)

- Purpose: The Extended GTT is used to assess glucose metabolism over a longer period, typically to evaluate for reactive hypoglycemia or delayed glucose intolerance.

- Procedure:

- Similar to the standard OGTT, but blood glucose levels are measured over a more extended period, such as 3, 4, or 5 hours after glucose ingestion.

- Blood samples may be taken at multiple intervals, such as every 30 minutes, to observe the glucose levels over time.

- Indications:

- Evaluation of patients with symptoms of hypoglycemia after meals.

- Assessment of individuals with a family history of diabetes or those who have abnormal results on a standard OGTT.

- Interpretation:

- A prolonged elevated glucose level indicates impaired glucose tolerance or diabetes.

- A significant drop in glucose levels several hours after the test may indicate reactive hypoglycemia.

3. Glucose Challenge Test (GCT)

- Purpose: The GCT is primarily used as a screening tool for gestational diabetes in pregnant women.

- Procedure:

- The patient is given 50 grams of glucose, and blood glucose levels are measured 1 hour later.

- No fasting is required before the test.

- Indications:

- Routine screening for gestational diabetes, usually performed between 24 and 28 weeks of gestation.

- Interpretation:

- A 1-hour glucose level of ≥140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L) indicates a need for further testing with a full OGTT to diagnose gestational diabetes.

4. Intravenous Glucose Tolerance Test (IV GTT)

- Purpose: The IV GTT is used to assess insulin secretion and glucose metabolism without the influence of gastrointestinal factors, which can affect glucose absorption in the oral test.

- Procedure:

- Instead of oral glucose ingestion, a known amount of glucose is administered intravenously over a few minutes.

- Blood samples are taken at baseline and at several intervals after the glucose infusion to measure blood glucose and insulin levels.

- Indications:

- Evaluation of beta-cell function and insulin sensitivity in patients with suspected diabetes.

- Situations where oral glucose administration is not feasible, such as in patients with malabsorption syndromes or severe gastrointestinal disorders.

- Interpretation:

- A normal response shows a rapid rise in blood glucose followed by a swift return to baseline, with corresponding insulin release.

- A delayed insulin response or prolonged hyperglycemia may indicate impaired glucose tolerance, insulin resistance, or beta-cell dysfunction.

Different variations of the Glucose Tolerance Test are used depending on the clinical context and the specific information needed about a patient’s glucose metabolism. The Mini GTT, Extended GTT, GCT, and IV GTT each serve unique purposes and help in the accurate diagnosis and management of conditions like diabetes, gestational diabetes, reactive hypoglycemia, and insulin resistance. Understanding the indications and interpretation of these tests is essential for clinicians to provide effective care.

HbA1c Definition

Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) is a form of hemoglobin that is chemically linked to glucose. It is used as a key marker in the monitoring and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. The HbA1c test measures the average blood glucose levels over the past two to three months by assessing the percentage of hemoglobin molecules in the blood that have glucose attached to them.

Key Points about HbA1c:

- What it Represents: HbA1c reflects the average blood glucose concentration over the lifespan of red blood cells (approximately 120 days). As blood glucose levels increase, more glucose binds to hemoglobin, leading to a higher HbA1c percentage.

- Diagnostic Criteria:

- Normal: HbA1c < 5.7%

- Prediabetes: HbA1c 5.7% – 6.4%

- Diabetes: HbA1c ≥ 6.5% (on two separate occasions or with other confirmatory tests)

- Target Levels for Management:

- For most people with diabetes, an HbA1c level below 7% is recommended, though individual targets may vary based on factors like age, comorbidities, and risk of hypoglycemia.

- Advantages:

- Provides a long-term indicator of blood glucose control, which is less affected by short-term fluctuations in glucose levels due to factors like diet, exercise, or illness.

- Limitations:

- HbA1c may be affected by conditions that alter red blood cell turnover or hemoglobin variants, such as anemia, hemoglobinopathies, or recent blood loss/transfusions, which can make the result less accurate.

In summary, HbA1c is an essential tool in the diagnosis and management of diabetes, providing valuable information on long-term blood glucose control and helping guide treatment decisions to reduce the risk of diabetes-related complications.

Hypoglycemia: Definition and Causes

Hypoglycemia is a condition characterized by abnormally low blood glucose (sugar) levels, typically below 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L), although the threshold may vary slightly depending on the individual and specific clinical circumstances. It is a medical emergency that requires prompt recognition and treatment to prevent serious complications.

Definition:

- Hypoglycemia occurs when blood glucose levels fall below the normal range, resulting in insufficient glucose available for the body’s cells, particularly the brain, which relies heavily on glucose for energy. The symptoms of hypoglycemia can vary from mild to severe and can progress rapidly if not treated.

Causes of Hypoglycemia:

- Medication-Induced Hypoglycemia:

- Insulin: Excessive doses of insulin, particularly in people with diabetes, are a common cause of hypoglycemia. This can occur due to errors in dosing, changes in activity levels, or missed meals.

- Oral Hypoglycemic Agents: Medications like sulfonylureas (e.g., glipizide, glyburide) and meglitinides, which increase insulin production, can cause hypoglycemia, especially if meals are skipped or delayed.

- Fasting or Prolonged Starvation:

- Inadequate Food Intake: Skipping meals, fasting, or not consuming enough carbohydrates can lead to hypoglycemia, particularly in people with diabetes who are on insulin or other glucose-lowering medications.

- Prolonged Exercise: Extended periods of physical activity without adequate food intake can deplete glucose stores and lead to hypoglycemia.

- Alcohol-Induced Hypoglycemia:

- Excessive Alcohol Consumption: Alcohol can inhibit glucose production in the liver, particularly when consumed in large quantities without food, leading to hypoglycemia.

- Hormonal Deficiencies:

- Adrenal Insufficiency: Lack of cortisol, a hormone produced by the adrenal glands, can result in impaired glucose production and hypoglycemia.

- Growth Hormone Deficiency: In children, a lack of growth hormone can cause hypoglycemia, as this hormone plays a role in maintaining normal blood glucose levels.

- Insulinoma: A rare tumor of the pancreas that produces excess insulin, leading to frequent episodes of hypoglycemia.

- Critical Illnesses:

- Severe Liver Disease: The liver plays a crucial role in glucose production. Liver failure or severe liver disease can impair this function and lead to hypoglycemia.

- Kidney Failure: Reduced clearance of insulin or oral hypoglycemic drugs in kidney failure can lead to hypoglycemia.

- Sepsis: Severe infections can cause hypoglycemia due to increased glucose consumption by tissues, impaired glucose production, or as a side effect of treatment.

- Reactive Hypoglycemia:

- Postprandial Hypoglycemia: Occurs when blood glucose levels drop too low after eating, typically within a few hours. This can happen due to an exaggerated insulin response, often seen in individuals with prediabetes or after gastric surgery.

- Glycogen Storage Diseases:

- Genetic Disorders: Conditions such as glycogen storage diseases, where the body’s ability to store or break down glycogen is impaired, can lead to recurrent hypoglycemia.

- Autoimmune Hypoglycemia:

- Autoimmune Insulin Syndrome (Hirata’s Disease): A rare condition where autoantibodies against insulin or the insulin receptor cause hypoglycemia.

Hypoglycemia is a potentially dangerous condition that can arise from various causes, including medication errors, inadequate food intake, excessive exercise, alcohol consumption, hormonal deficiencies, critical illnesses, and rare genetic or autoimmune disorders. Recognizing the signs and causes of hypoglycemia is crucial for timely intervention and prevention of severe complications such as seizures, unconsciousness, and even death.

FOR UNLOCK 🔓 FULL COURSE NOW. MORE DETAILS CALL US OR WATSAPP ON- 8485976407