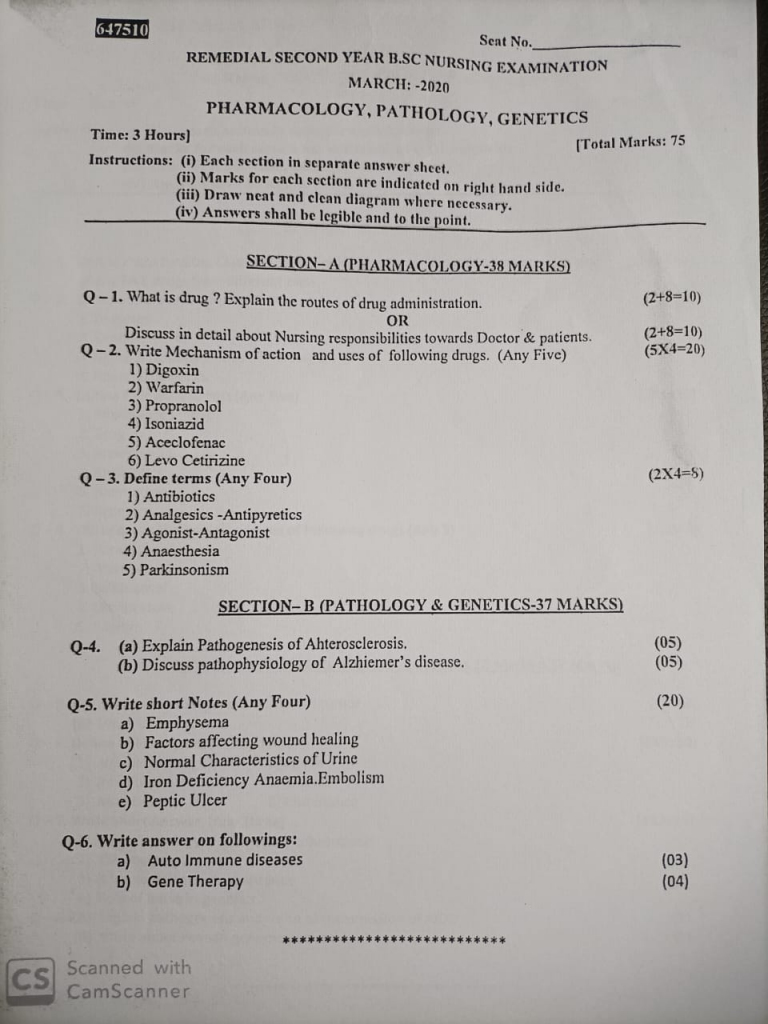

😡B.SC NURSING- MARCH: -2020- PHARMACOLOGY, PATHOLOGY, GENETICS(UPLOAD PAPER NO.2)

B.SC NURSING- MARCH: -2020- PHARMACOLOGY, PATHOLOGY, GENETICS (BKNMU)

🔸SECTION-A 🔸PHARMACOLOGY-38 MARKS)

🔸Q-1. What is drug ? Explain the routes of drug administration.

What is a Drug

A drug is a substance used to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent diseases or to enhance physical or mental well-being. Drugs can alter physiological functions, affecting the body and mind. They can be natural or synthetic and are usually administered in various forms like tablets, injections, or topical applications.

Routes of Drug Administration

The route of drug administration refers to the method by which a drug is delivered into the body. Different routes can affect the speed and efficiency of drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion. Here are the main routes of drug administration:

Oral Administration

Drugs are taken by mouth and absorbed through the digestive tract. This is the most common and convenient route but can be affected by factors like stomach acidity and digestive enzymes.

Intravenous Administration

Drugs are injected directly into the bloodstream through a vein. This route offers immediate effect and precise control over drug levels but requires medical expertise.

Intramuscular Administration

Drugs are injected into a muscle. This route allows for slower, sustained release of the drug into the bloodstream.

Subcutaneous Administration

Drugs are injected into the tissue layer between the skin and muscle. This method is used for drugs that require slow, sustained absorption.

Sublingual Administration

Drugs are placed under the tongue, where they dissolve and are absorbed directly into the bloodstream. This route provides rapid absorption and onset of action.

Rectal Administration

Drugs are administered via the rectum. This method can be used for patients who cannot take drugs orally and can be useful for localized treatment.

Topical Administration

Drugs are applied directly to the skin or mucous membranes. This route is used for local effects, such as in ointments or creams.

Inhalation

Drugs are inhaled into the lungs, where they are absorbed into the bloodstream. This route is commonly used for respiratory conditions.

Transdermal Administration

Drugs are delivered through the skin via patches. This method provides a continuous, controlled release of the drug over a period.

Intranasal Administration

Drugs are delivered through the nasal passages. This route allows for rapid absorption and is used for both local and systemic effects.

Each route of administration has its advantages and limitations, and the choice depends on the drug’s characteristics, the condition being treated, and patient considerations.

🔸OR🔸

🔸Discuss in detail about Nursing responsibilities towards Doctor & patients.

Nursing Responsibilities Towards Doctors

Nurses play a vital role in the healthcare system, working closely with doctors to ensure the best patient outcomes. Their responsibilities towards doctors include several key areas:

- Effective Communication

Nurses are responsible for clear, concise, and timely communication with doctors. This involves relaying important information about patient conditions, changes in symptoms, or reactions to treatments. Nurses must be able to accurately report observations and provide updates that help doctors make informed decisions.

- Providing Accurate Patient Data

Nurses collect and document vital signs, medical histories, and patient responses to treatments. They ensure that all information is accurate and up-to-date, which is crucial for doctors to assess the effectiveness of treatments and adjust care plans as needed.

- Following Medical Orders

Nurses are responsible for carrying out doctors’ orders regarding medications, therapies, and other treatments. This includes administering medications as prescribed, performing procedures, and ensuring that all instructions are followed precisely.

- Assisting with Procedures

Nurses assist doctors during medical procedures and surgeries. This may involve preparing the patient, providing necessary instruments or materials, and ensuring that the environment is sterile and organized. Their support helps ensure that procedures are performed safely and effectively.

- Offering Professional Support

Nurses offer professional support to doctors by providing input based on their clinical observations and experience. They may suggest alternative treatment options or highlight issues that the doctor might not have considered, fostering a collaborative approach to patient care.

Nursing Responsibilities Towards Patients

Nurses have a range of responsibilities towards patients, focusing on their well-being, safety, and comfort:

- Providing Compassionate Care

Nurses are responsible for delivering care with empathy and understanding. They must address patients’ emotional, psychological, and physical needs, offering reassurance and support throughout their healthcare journey.

- Monitoring and Assessing Patient Conditions

Nurses regularly monitor patients’ vital signs, symptoms, and overall health. They assess changes in patient conditions and report these observations to doctors. This ongoing assessment is crucial for adjusting treatment plans and ensuring patient safety.

- Educating Patients and Families

Nurses provide education to patients and their families about medical conditions, treatments, and care plans. They explain procedures, answer questions, and offer guidance on managing health conditions at home, helping patients make informed decisions about their care.

- Advocating for Patient Rights

Nurses advocate for patients’ rights and ensure that their voices are heard. They work to protect patients from harm, respect their wishes and preferences, and uphold ethical standards in all aspects of care.

- Ensuring Patient Safety

Nurses are responsible for creating and maintaining a safe environment for patients. This includes preventing falls, managing infection control, and ensuring that all equipment and procedures adhere to safety standards.

- Coordinating Care

Nurses coordinate care among various healthcare providers, ensuring that all aspects of a patient’s treatment plan are integrated and effective. They act as a liaison between patients, doctors, and other healthcare professionals to ensure comprehensive care.

nurses have multifaceted roles that involve collaborating with doctors and advocating for patients. Effective communication, professional support, and compassionate care are essential components of their responsibilities in both areas.

Q-2. Write Mechanism of action and uses of following drugs. (Any Five)

🔸1) Digoxin

Mechanism of Action of Digoxin

Digoxin is a cardiac glycoside that exerts its effects through multiple mechanisms:

1.Inhibition of Na+/K+ ATPase:

Digoxin inhibits the Na+/K+ ATPase pump on the cardiac cell membrane. This inhibition increases intracellular sodium levels, which leads to increased intracellular calcium through the sodium-calcium exchanger.

2.Increased Intracellular Calcium:

The rise in intracellular calcium enhances the force of myocardial contraction (positive inotropic effect), improving cardiac output.

3.Effects on Autonomic Nervous System:

Digoxin increases vagal (parasympathetic) tone and decreases sympathetic activity, which leads to a reduction in heart rate and AV node conduction.

Uses of Digoxin

Digoxin is used for several cardiovascular conditions, including:

1.Heart Failure:

It is used to improve symptoms and reduce hospitalizations in patients with heart failure, particularly in cases of reduced ejection fraction.

2.Atrial Fibrillation and Atrial Flutter:

Digoxin helps to control ventricular rate in patients with atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter.

3.Supraventricular Tachycardias:

It can be used to manage certain types of supraventricular tachycardias due to its effects on the AV node.

Digoxin is a key medication in managing these conditions due to its effects on cardiac contractility and heart rate.

🔸2) Warfarin

Mechanism of Action of Warfarin

Warfarin is an oral anticoagulant that works by interfering with the synthesis of vitamin K-dependent clotting factors. Its mechanism of action includes:

1.Inhibition of Vitamin K Epoxide Reductase: Warfarin inhibits the enzyme vitamin K epoxide reductase, which is crucial for the reduction of vitamin K. This enzyme is necessary for the synthesis of active forms of vitamin K.

2.Reduction of Vitamin K-Dependent Clotting Factors:

By inhibiting vitamin K epoxide reductase, warfarin decreases the levels of vitamin K, leading to a reduction in the synthesis of vitamin K-dependent clotting factors such as Factor II (prothrombin), Factor VII, Factor IX, and Factor X. These factors are essential for the blood clotting process.

3.Extended Onset:

The anticoagulant effect of warfarin develops slowly because it affects the synthesis of new clotting factors rather than modifying existing ones. This results in a delay before clinical effects are observed.

Uses of Warfarin

Warfarin is used for the prevention and treatment of various thromboembolic conditions, including:

1.Prevention of Stroke in Atrial Fibrillation:

Warfarin is commonly prescribed to reduce the risk of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation by preventing the formation of blood clots in the heart.

2.Treatment of Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) and Pulmonary Embolism (PE):

It is used for the treatment and prevention of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, which are conditions where blood clots form in the veins or lungs.

3.Prevention of Thromboembolism in Mechanical Heart Valves:

Warfarin helps prevent the formation of clots in patients with mechanical heart valves.

4.Management of Myocardial Infarction:

It can be used to reduce the risk of recurrent myocardial infarction and complications related to coronary artery disease.

Warfarin’s role in these conditions is to reduce the risk of dangerous blood clots that could lead to serious cardiovascular events.

🔸3) Propranolol

Propranolol

Mechanism of Action of Propranolol

Propranolol is a non-selective beta-adrenergic antagonist. Its primary mechanisms of action are:

1 Beta-Blockade: Propranolol blocks beta-1 and beta-2 adrenergic receptors. Beta-1 receptors are primarily located in the heart, while beta-2 receptors are found in the lungs, blood vessels, and other tissues.

2.Reduction of Heart Rate and Contractility:

By blocking beta-1 receptors in the heart, propranolol decreases heart rate (negative chronotropic effect) and myocardial contractility (negative inotropic effect), which leads to a reduction in cardiac output.

3.Decrease in Renin Release:

Propranolol inhibits the release of renin from the kidneys, which reduces the production of angiotensin I and subsequently angiotensin II. This leads to vasodilation and a decrease in blood pressure.

4.Decrease in Sympathetic Nervous System Activity:

By blocking beta-2 receptors, propranolol reduces the effects of sympathetic stimulation on various tissues, including the heart and blood vessels.

Uses of Propranolol

Propranolol is used for a range of cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular conditions, including:

1.Hypertension:

It is used to lower blood pressure by reducing cardiac output and inhibiting the renin-angiotensin system.

2.Angina Pectoris:

Propranolol helps relieve angina symptoms by decreasing the heart’s oxygen demand through its effects on heart rate and contractility.

3.Myocardial Infarction:

It is used to reduce mortality and prevent subsequent heart attacks in patients who have experienced a myocardial infarction.

4.Arrhythmias:

Propranolol is effective in managing certain types of arrhythmias, including atrial fibrillation and ventricular arrhythmias, by stabilizing heart rhythm.

5.Migraine Prophylaxis:

It is used as a preventive treatment for migraines due to its effects on vascular tone and central nervous system modulation.

6.Essential Tremor:

Propranolol is prescribed to reduce the severity of essential tremor, a condition characterized by involuntary shaking.

Propranolol’s diverse uses stem from its ability to modulate both cardiac and systemic sympathetic activity.

🔸4) Isoniazid

Isoniazid

Mechanism of Action of Isoniazid

Isoniazid is a first-line antibiotic used in the treatment of tuberculosis (TB). Its mechanism of action involves:

1.Inhibition of Mycolic Acid Synthesis:

Isoniazid is a prodrug that is activated by the bacterial enzyme catalase-peroxidase (KatG). The active form of isoniazid inhibits the enzyme enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase (InhA), which is crucial for the synthesis of mycolic acids. Mycolic acids are essential components of the mycobacterial cell wall.

2.Disruption of Cell Wall Synthesis:

By inhibiting the synthesis of mycolic acids, isoniazid disrupts the formation of the mycobacterial cell wall, leading to bacterial cell death.

3.Bactericidal and Bacteriostatic Effects:

Isoniazid has bactericidal effects against actively dividing Mycobacterium tuberculosis and can also exhibit bacteriostatic effects against non-replicating bacteria.

Uses of Isoniazid

Isoniazid is primarily used for the treatment and prevention of tuberculosis. Its uses include:

1.Treatment of Active Tuberculosis:

Isoniazid is a key component of multi-drug regimens used to treat active TB infections. It is typically used in combination with other antitubercular drugs such as rifampin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide.

2.Latent Tuberculosis Infection:

Isoniazid is used as a monotherapy for the treatment of latent TB infection to prevent the development of active TB disease. This is usually given as a 6- to 9-month course.

3.Prevention of Tuberculosis in High-Risk Individuals:

Isoniazid is used for TB prophylaxis in individuals who have been in close contact with someone with active TB or who have a high risk of developing TB.

Isoniazid’s role in TB treatment and prevention is fundamental due to its effectiveness against the Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria.

🔸5) Aceclofenac

Aceclofenac

Mechanism of Action of Aceclofenac

Aceclofenac is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID). Its mechanism of action involves:

1.Inhibition of Cyclooxygenase Enzymes:

Aceclofenac inhibits cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) enzymes. These enzymes are responsible for the conversion of arachidonic acid to prostaglandins.

2.Reduction of Prostaglandin Synthesis:

By inhibiting COX enzymes, aceclofenac decreases the synthesis of prostaglandins, which are mediators of inflammation, pain, and fever.

3.Anti-inflammatory, Analgesic, and Antipyretic Effects:

The reduction in prostaglandin levels leads to decreased inflammation, relief of pain, and reduction of fever.

Uses of Aceclofenac

Aceclofenac is used to manage various inflammatory and pain-related conditions, including:

1.Osteoarthritis:

It is used to relieve pain and reduce inflammation associated with osteoarthritis.

2.Rheumatoid Arthritis:

Aceclofenac helps manage the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis, including pain and joint inflammation.

3.Ankylosing Spondylitis:

It is prescribed for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis, a type of inflammatory arthritis affecting the spine.

4.Acute Musculoskeletal Pain:

Aceclofenac is used for short-term relief of acute pain from conditions such as muscle strains and back pain.

Aceclofenac is effective in treating conditions characterized by inflammation and pain due to its dual action of COX inhibition.

🔸6) Levo Cetirizine

Levocetirizine

Mechanism of Action of Levocetirizine

Levocetirizine is a second-generation antihistamine. Its mechanism of action includes:

1.H1 Receptor Antagonism:

Levocetirizine selectively antagonizes H1 histamine receptors on target cells. By blocking these receptors, it prevents the effects of histamine, which include itching, sneezing, and increased vascular permeability.

2.Reduction of Allergic Responses:

By inhibiting H1 receptor activation, levocetirizine reduces the symptoms of allergic reactions, such as rhinitis and conjunctivitis.

3.Minimal Central Nervous System Penetration:

Compared to first-generation antihistamines, levocetirizine has minimal penetration into the central nervous system, resulting in fewer sedative effects.

Uses of Levocetirizine

Levocetirizine is used for the treatment of various allergic conditions, including:

1.Allergic Rhinitis:

It is used to relieve symptoms of both seasonal and perennial allergic rhinitis, such as sneezing, nasal congestion, and runny nose.

2.Chronic Urticaria:

Levocetirizine helps manage chronic urticaria (hives), providing relief from itching and rash.

3.Allergic Conjunctivitis:

It is used to treat symptoms of allergic conjunctivitis, such as itchy and watery eyes.

Levocetirizine is effective in managing allergic conditions due to its selective H1 receptor antagonism and reduced sedative effects.

Q-3. Define terms (Any Four)

🔸1) Antibiotics

Antibiotics

Definition of Antibiotics

Antibiotics are a class of medications used to treat bacterial infections. They work by targeting specific features of bacterial cells to either kill the bacteria (bactericidal) or inhibit their growth (bacteriostatic).

Characteristics of Antibiotics

1 Selective Toxicity:

Antibiotics target bacterial structures or functions that are different from those in human cells, such as the bacterial cell wall, ribosomes, or metabolic pathways.

2.Spectrum of Activity:

Antibiotics can have a broad spectrum (effective against a wide range of bacteria) or a narrow spectrum (effective against specific types of bacteria).

3.Mechanisms of Action:

They can work through various mechanisms, including inhibiting cell wall synthesis, protein synthesis, nucleic acid synthesis, or metabolic processes.

Types of Antibiotics

1.Bactericidal Antibiotics:

These kill bacteria directly, such as penicillin and ciprofloxacin.

2.Bacteriostatic Antibiotics:

These inhibit bacterial growth and replication, such as tetracycline and sulfonamides.

Antibiotics are crucial in treating bacterial infections but are not effective against viral, fungal, or parasitic infections.

🔸2) Analgesics-Antipyretics

Definition of Analgesics

Analgesics are a class of drugs designed to relieve pain. They work through various mechanisms to reduce the perception of pain without causing loss of consciousness.

Characteristics of Analgesics

1.Pain Relief:

Analgesics provide relief from mild to severe pain caused by various conditions, including injury, surgery, or chronic diseases.

2.Mechanisms of Action:

Analgesics can work by inhibiting pain signal transmission through the central nervous system or by blocking the production of pain-causing substances like prostaglandins.

3.Types of Analgesics:

They can be classified as non-opioid analgesics (e.g., acetaminophen, NSAIDs), opioid analgesics (e.g., morphine, oxycodone), or adjuvant analgesics (e.g., antidepressants for neuropathic pain).

Definition of Antipyretics AAntipyretics are medications used to reduce fever. They work by acting on the hypothalamus to lower the body’s temperature set-point.

Characteristics of Antipyretics

1.Fever Reduction:

Antipyretics help decrease elevated body temperature associated with fever due to infections or other conditions.

2.Mechanisms of Action:

They reduce fever by inhibiting the synthesis of prostaglandins in the hypothalamus, which lowers the body’s temperature set-point.

3.Types of Antipyretics:

Common antipyretics include acetaminophen (paracetamol) and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen.

Overlap of Analgesics and Antipyretics

Some medications, like acetaminophen and NSAIDs, have both analgesic and antipyretic properties, meaning they can relieve pain and reduce fever simultaneously.

🔸3) Agonist-Antagonist

Agonist- Antagonists

Definition of Agonist

An agonist is a substance that binds to a specific receptor and activates it, mimicking the action of a naturally occurring substance.

Characteristics of Agonists

1.Receptor Activation:

Agonists bind to receptor sites on cells and trigger a response that is similar to the effect of the endogenous ligand.

2.Types of Agonists:

Full Agonists:

These bind to receptors and produce a maximal response (e.g., morphine at opioid receptors).

Partial Agonists:

These bind to receptors and activate them but produce a less than maximal response (e.g., buprenorphine at opioid receptors).

Inverse Agonists:

These bind to the same receptors as agonists but induce the opposite effect (e.g., certain drugs at histamine H1 receptors).

3.Effects:

The effects of agonists depend on the type of receptor they activate and include actions like stimulation of muscle contraction, neurotransmitter release, or hormone secretion.

Definition of Antagonist

An antagonist is a substance that binds to a specific receptor but does not activate it, instead blocking the receptor and preventing it from responding to agonists.

Characteristics of Antagonists

1.Receptor Blockade:

Antagonists bind to receptor sites but do not trigger a biological response. Their primary role is to prevent agonists from binding and activating the receptor.

2.Types of Antagonists:

Competitive Antagonists:

These bind reversibly to the receptor and can be displaced by an increasing concentration of agonists (e.g., naloxone for opioid overdose).

Non-Competitive Antagonists:

These bind irreversibly or allosterically to the receptor, preventing agonist binding regardless of agonist concentration (e.g., ketamine as an NMDA receptor antagonist).

3.Effects:

Antagonists block the physiological effects of agonists, which can be used to counteract excessive receptor activation or treat conditions caused by excessive receptor stimulation.

Comparison of Agonists and Antagonists

Agonists

activate receptors and produce a biological response.

Antagonists

block receptor activation and prevent a biological response.

These definitions explain the roles of agonists and antagonists in pharmacology and their impact on receptor-mediated physiological processes.

🔸4) Anaesthesia

Anesthesia is a medical practice aimed at preventing pain and discomfort during surgical and medical procedures. It involves the use of medications and techniques to induce a temporary loss of sensation or consciousness. There are different types of anesthesia tailored to the needs of the patient and the procedure.

- Types of Anesthesia

General Anesthesia

Definition:

A state of controlled unconsciousness where the patient is entirely unaware of the procedure.

Techniques:

Inhalational Anesthetics:

Gases or vapors administered through the respiratory tract (e.g., sevoflurane, isoflurane).

Intravenous Anesthetics:

Medications injected directly into the bloodstream (e.g., propofol, etomidate).

Uses:

Major surgeries (e.g., abdominal surgery, open-heart surgery).

Procedures requiring complete sedation.

Monitoring:

Vital signs, depth of anesthesia, and patient response.

Regional Anesthesia

Definition:

Blocks sensation in a specific area of the body, while the patient remains awake or sedated.

Techniques:

Spinal Anesthesia:

Injection into the cerebrospinal fluid in the lumbar region (e.g., for cesarean sections).

Epidural Anesthesia

Injection into the epidural space of the spinal cord (e.g., for labor pain relief).

Nerve Blocks

Local anesthetic injected around a specific nerve (e.g., for limb surgery).

Uses:

Childbirth.

Lower body surgeries (e.g., hip replacement).

Monitoring:

Sensation and movement of the affected area, vital signs.

Local Anesthesia

Definition:

Numbs a small, specific area of the body.

🔸5) Parkinsonism

Definition of Parkinsonism

Parkinsonism refers to a group of neurological disorders characterized by motor symptoms similar to those seen in Parkinson’s disease.

Characteristics of Parkinsonism

1.Core Symptoms:

Parkinsonism is defined by a combination of the following symptoms:

Tremor:

Typically a resting tremor that occurs when the muscles are at rest and decreases with movement.

Bradykinesia:

Slowness of movement that affects the initiation and execution of voluntary movements.

Rigidity:

Increased muscle tone that causes resistance to passive movement of the limbs.

Postural Instability:

Difficulty maintaining balance and coordination, which increases the risk of falls.

🔸SECTION-B🔸 (PATHOLOGY & GENETICS-37 MARKS)

Q-4. 🔸(a) Explain Pathogenesis of Ahterosclerosis.

Pathogenesis of Atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease of the arterial wall characterized by the formation of atherosclerotic plaques. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis involves several key steps:

- Endothelial Injury The initial step in the development of atherosclerosis is endothelial injury. Factors contributing to endothelial injury include:

Hypertension:

High blood pressure causes mechanical stress on the endothelial cells lining the blood vessels.

Hyperlipidemia:

Elevated levels of lipids, particularly low-density lipoprotein (LDL), can damage the endothelium.

Smoking: Tobacco smoke introduces toxins that injure endothelial cells.

Diabetes:

High blood sugar levels cause endothelial dysfunction.

- Lipoprotein Accumulation

Following endothelial injury, lipoproteins accumulate in the arterial wall. This includes:

LDL Penetration:

LDL particles cross the damaged endothelium and deposit in the subendothelial space.

Oxidation of LDL:

LDL particles become oxidized, which is a key event in atherosclerosis. Oxidized LDL is more atherogenic and triggers inflammatory responses.

- Inflammatory Response The accumulation of oxidized LDL in the arterial wall activates an inflammatory response. This involves:

Recruitment of Immune Cells: Monocytes adhere to the endothelial surface and migrate into the intima, where they differentiate into macrophages.

Phagocytosis of Oxidized LDL:

Macrophages engulf oxidized LDL and become foam cells, which contribute to plaque formation.

- Formation of Atherosclerotic Plaques The inflammatory response leads to the formation of atherosclerotic plaques. This process includes:

Smooth Muscle Cell Proliferation:

Smooth muscle cells migrate from the media to the intima and proliferate.

Extracellular Matrix Formation:

Smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts produce extracellular matrix components, including collagen and elastin, which form the fibrous cap of the plaque.

Formation of a Fibrous Plaque:

The accumulation of foam cells, smooth muscle cells, extracellular matrix, and inflammatory cells creates a fibrous plaque with a lipid-rich core.

- Plaque Progression and Complications As atherosclerotic plaques grow, they can lead to various complications:

Plaque Instability:

The fibrous cap can become thin and rupture, exposing the thrombogenic core to the bloodstream.

Thrombosis:

Plaque rupture triggers platelet aggregation and blood clot formation, which can occlude the artery and lead to acute events like myocardial infarction or stroke.

Aneurysm Formation:

Chronic plaque buildup can weaken the arterial wall, potentially leading to aneurysm formation.

- Clinical Manifestations The progression of atherosclerosis can lead to clinical manifestations, such as:

Coronary Artery Disease:

Reduced blood flow to the heart muscle can cause angina or myocardial infarction.

Stroke:

Atherosclerosis in the carotid arteries can lead to cerebrovascular accidents.

Peripheral Artery Disease:

Reduced blood flow to the limbs can cause pain and mobility issues.

🔸(b) Discuss pathophysiology of Alzhiemer’s disease.

Pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that leads to cognitive decline and memory loss. The pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s disease involves several interconnected mechanisms and changes in the brain.

- Amyloid Beta Plaque Formation One of the hallmark features of Alzheimer’s disease is the accumulation of amyloid beta plaques in the brain.

Amyloid Precursor Protein (APP) Processing:

APP is cleaved by beta-secretase and gamma-secretase enzymes to produce amyloid beta peptides.

Formation of Amyloid Beta Plaques:

These peptides aggregate to form insoluble amyloid beta plaques, which disrupt cell function and trigger inflammatory responses.

- Neurofibrillary Tangles Neurofibrillary tangles are another key feature of Alzheimer’s disease.

Hyperphosphorylation of Tau Protein:

Tau, a protein that stabilizes microtubules, becomes hyper phosphorylated

d Formation of Tangled Neurofibrils:

Hyperphosphorylated tau proteins aggregate into twisted neurofibrillary tangles, disrupting neuronal transport systems and contributing to cell death.

- Neuronal Loss and Synaptic Dysfunction The presence of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles leads to widespread neuronal loss and synaptic dysfunction.

Neuronal Death:

Plaques and tangles cause neuronal damage and death, particularly in the hippocampus and cortex, which are crucial for memory and cognitive functions.

Synaptic Loss:

The degeneration of neurons leads to the loss of synaptic connections, further impairing communication between neurons.

- Inflammation and Oxidative Stress

Inflammation and oxidative stress play significant roles in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease.

Microglial Activation:

Amyloid plaques activate microglia, the brain’s immune cells, leading to chronic inflammation.

Oxidative Damage:

The accumulation of amyloid beta and other factors induces oxidative stress, causing damage to lipids, proteins, and DNA in neurons.

- Neurochemical Changes

Several neurochemical imbalances are observed in Alzheimer’s disease.

Cholinergic Deficits:

. There is a significant loss of cholinergic neurons and a decrease in acetylcholine levels, which impairs memory and cognitive function.

Glutamatergic Dysregulation:

There is dysregulation of glutamate, an excitatory neurotransmitter, which may contribute to excitotoxicity and neuronal death.

- Genetic and Factors Genetic and environmental factors also contribute to the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease.

- Genetic Risk Factors:

Mutations in genegs such as APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 are associated with early-onset Alzheimer’s. The apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 allele is a major genetic risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer’s.

Environmental Influences:

Factors like aging, cardiovascular health, and lifestyle choices also impact the risk and progression of Alzheimer’s disease.

- Clinical Manifestations

The pathophysiological changes in Alzheimer’s disease lead to specific clinical manifestations:

Memory Loss:

Progressive impairment of short-term memory and learning abilities.

Cognitive Decline:

Difficulty with thinking, reasoning, and problem-solving.

Behavioral Changes:

Symptoms such as agitation, depression, and delusions can occur.

Q-5. Write short Notes (Any Four)

🔸a) Emphysema

Definition of Emphysema

Emphysema is a chronic respiratory condition characterized by the destruction of the alveoli, the small air sacs in the lungs where gas exchange occurs. This destruction leads to reduced surface area for gas exchange and impaired lung function.

Pathophysiology of Emphysema

The pathophysiology of emphysema involves several key mechanisms:

- Destruction of Alveolar Walls

Protease-Antiprotease Imbalance:

Emphysema is primarily caused by an imbalance between proteases and antiproteases. Proteases like neutrophil elastase, which break down elastin in the alveolar walls, are normally inhibited by antiproteases such as alpha-1 antitrypsin. In emphysema, this balance is disrupted, leading to excessive breakdown of elastin.

Elastin Degradation: Increased protease activity degrades the elastin in the alveolar walls, leading to the destruction of alveolar structure. This results in the enlargement of air spaces and loss of elastic recoil in the lungs.

- Airway Remodeling

Loss of Elastic Recoil: The destruction of alveolar walls reduces the elastic recoil of the lungs, impairing the ability of the lungs to expel air during expiration.

Air Trapping:

The loss of elastic recoil and destruction of alveolar structures cause air trapping in the lungs, leading to hyperinflation.

- Impaired Gas Exchange

Decreased Surface Area:

The destruction of alveoli reduces the surface area available for gas exchange, which impairs the efficiency of oxygen and carbon dioxide exchange between the blood and the air.

Ventilation-Perfusion Mismatch:

The destruction of alveoli and changes in the structure of the lungs lead to ventilation-perfusion mismatch, where some parts of the lung receive less ventilation relative to blood flow, affecting gas exchange.

- Inflammation and Oxidative Stress

Inflammatory Response:

Chronic inflammation caused by irritants like cigarette smoke or environmental pollutants triggers the release of inflammatory mediators and proteases, contributing to alveolar damage.

Oxidative Stress:

Increased oxidative stress from cigarette smoke or other pollutants leads to further damage of lung tissues and exacerbates the inflammatory response.

Risk Factors for Emphysema

Several factors contribute to the development and progression of emphysema:

Smoking:

The primary risk factor for emphysema; smoking causes chronic inflammation and protease-antiprotease imbalance.

Environmental Pollutants: Long-term exposure to air pollutants and occupational hazards can contribute to emphysema.

Genetic Factors:

Genetic predispositions, such as alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, can lead to early-onset emphysema.

Clinical Manifestations of Emphysema

The clinical features of emphysema include:

Dyspnea:

Shortness of breath, which initially occurs during exertion but can progress to occur at rest.

Chronic Cough:

A persistent cough that may produce minimal sputum.

Wheezing:

A whistling sound during breathing due to narrowed airways.

Barrel Chest:

A chest shape that resembles a barrel due to lung hyperinflation.

Diagnosis of Emphysema

Diagnosis is based on:

Clinical Evaluation:

Assessment of symptoms and medical history.

Imaging Studies:

Chest X-rays and CT scans show hyperinflation of the lungs and destruction of alveolar structures.

Pulmonary Function Tests: Tests such as spirometry reveal reduced expiratory airflow and increased residual volume.

Treatment of Emphysema

Management includes:

Smoking Cessation:

The most effective treatment to slow disease progression.

Medications:

Bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids to manage symptoms.

Oxygen Therapy:

For patients with advanced disease and low blood oxygen levels.

Pulmonary Rehabilitation:

A program to improve physical fitness and respiratory function.

🔸b) Factors affecting wound healing

Factors Affecting Wound Healing

Wound healing is a complex biological process influenced by a variety of intrinsic and extrinsic factors. These factors can either facilitate or hinder the healing process.

*1. Local Factors

Local factors are those that directly affect the wound environment and include:

Wound Infection: Infection introduces bacteria into the wound, causing inflammation and tissue damage which impedes healing.

Wound Size and Type:

Larger wounds or those with complex structures, such as deep punctures, are more challenging to heal.

Oxygenation:* Adequate oxygen is essential for wound healing. Poor oxygenation, due to conditions like hypoxia or poor blood supply, can slow the healing process.

Wound Care: Proper cleaning, dressing, and management of the wound environment are crucial for effective healing.

B b

. Systemic Factors

Systemic factors are related to the overall health of the individual and include:

Nutritional Status: Adequate intake of proteins, vitamins (such as vitamin C and A), and minerals (such as zinc) is essential for collagen synthesis and cellular function in wound healing.

Chronic Diseases:

Conditions like diabetes and cardiovascular diseases can impair healing by affecting blood flow, immune response, and tissue repair mechanisms.

Age: Older age is associated with slower wound healing due to decreased cellular regenerative capacity and reduced immune function.

Medications: Certain medications, such as corticosteroids and immunosuppressants, can impair wound healing by suppressing inflammation and immune responses.

- Immunological Factors

The immune system plays a critical role in wound healing, and factors include:

Immune Response: An adequate inflammatory response is required for clearing debris and pathogens. Both excessive inflammation and inadequate immune responses can delay healing.

Autoimmune Diseases:

Conditions where the immune system attacks the body’s own tissues, such as rheumatoid arthritis, can interfere with normal healing processes.

- Environmental Factors

Environmental mfactors influence the wound healing process and include:

Exposure to Irritants: Exposure to harmful substances like chemicals or toxins can damage the wound site and slow healing.

Temperature and Humidity: Extreme temperatures and humidity levels can affect the wound environment, either causing excessive dryness or promoting infection.

- Psychological Factors

Psychological well-being affects wound healing and includes:

Stress:

Chronic stress can negatively impact immune function and wound healing.

Mental Health: Conditions such as depression or anxiety can affect a person’s ability to adhere to treatment plans and maintain healthy behaviors.

- Vascular Factors

Vascular health is critical for wound healing, and factors include:

Blood Flow:

Adequate blood flow is necessary for delivering oxygen, nutrients, and cells required for healing. Conditions like peripheral vascular disease can impair blood circulation.

Vascular Insufficiency:

Poor vascularization can lead to inadequate supply of essential healing components and removal of waste products.

- Wound Environment

The physical conditions around the wound can impact healing:

Moisture Balance: Maintaining an appropriate moisture level in the wound is crucial. Too much moisture can lead to maceration, while too little can cause the wound to dry out.

Wound Temperature:

Maintaining a warm environment supports cellular metabolism and repair processes, while excessive heat can promote bacterial growth.

🔸c) Normal Characteristics of Urine

Normal Characteristics of Urine

Urine is a liquid byproduct of metabolism excreted by the kidneys. Its characteristics can provide valuable information about an individual’s health. The normal characteristics of urine include:

- Color

Normal Color: Urine typically ranges from pale yellow to deep amber.

Causes of Variation: The color is primarily due to the presence of urochrome, a pigment resulting from the breakdown of hemoglobin. Factors such as hydration status, diet, and medications can affect urine color.

- Transparency

Normal Transparency:

Urine is generally clear or slightly cloudy.

Causes of Cloudiness: Mild cloudiness can occur due to the presence of mucus or small amounts of cellular elements. Persistent cloudiness may indicate infection, dehydration, or other conditions.

- Odor

Normal Odor:

Urine has a slightly aromatic smell.

Causes of Odor Variation: The odor can be influenced by diet, medications, or health conditions. For example, asparagus or certain medications can cause a stronger odor, while a foul smell may indicate a urinary tract infection.

- pH Level

Normal pH Range:

Urine pH typically ranges from 4.5 to 8.0.

Factors Influencing pH: The pH of urine can vary based on diet (meat increases acidity, fruits and vegetables increase alkalinity), hydration levels, and metabolic conditions.

- Specific Gravity

Normal Specific Gravity: The specific gravity of urine ranges from 1.005 to 1.030.

Significance: This measure reflects the kidney’s ability to concentrate or dilute urine. Low specific gravity indicates diluted urine, while high specific gravity indicates concentrated urine.

- Osmolality Normal Osmolality:

Urine osmolality usually ranges from 300 to 900 mOsm/kg.

Importance:

Urine osmolality measures the concentration of solutes in urine, reflecting the kidney’s ability to regulate water balance and concentration of solutes.

- Composition

Normal Constituents:

Normal urine contains water (95%), urea, creatinine, uric acid, electrolytes (sodium, potassium, chloride), and trace amounts of other substances.

Absent or Minimal Substances: Normal urine should not contain significant amounts of glucose, protein, blood, ketones, or bacteria. Their presence can indicate conditions like diabetes, kidney disease, or infection.

- Volume

Normal Urine Output: The average urine output ranges from 800 to 2,000 mL per day in a healthy adult.

Variation Factors: Urine volume can be influenced by fluid intake, hydration status, and health conditions affecting kidney function.

- Sediment

Normal Sediment:

Urine sediment is minimal in healthy individuals.

Types of Sediment:

Sediment may include small amounts of cells, crystals, or casts. Increased sediment may indicate infection, kidney disease, or other urinary tract issues.

- Glucose

Normal Glucose Levels:

Urine glucose should be negative or present only in very small amounts.

Implications:

Glucose in the urine may indicate uncontrolled diabetes or other metabolic disorders.

- Protein

Normal Protein Levels:

Protein levels in urine are generally very low.

Significance: Persistent proteinuria may indicate kidney damage or disease.

🔸d) Iron Deficiency Anaemia. Embolism

Iron Deficiency Anemia

Definition

Iron deficiency anemia is a condition characterized by a reduction in red blood cells (RBCs) or hemoglobin levels due to insufficient iron, which is necessary for hemoglobin production.

Pathophysiology

Iron deficiency anemia occurs through the following processes:

- Decreased Iron Availability

Inadequate Dietary Intake: A diet lacking in iron-rich foods such as red meat, beans, and leafy greens.

Malabsorption: Conditions like celiac disease or surgical alterations of the digestive tract impair iron absorption.

2.Increased Iron Loss

Chronic Blood Loss: Conditions such as heavy menstrual bleeding, gastrointestinal bleeding (ulcers, hemorrhoids, malignancy), or frequent blood donations deplete iron stores.

Parasitic Infections:

Hookworms or other parasites can cause chronic blood loss, leading to iron deficiency.

3.Increased Iron Requirements

Pregnancy:

Increased iron demands for fetal growth and maternal blood volume.

Growth Spurts: Children and adolescents experience increased iron needs during rapid growth phases.

4.Decreased Hemoglobin Synthesis

Iron Deficiency: A lack of iron impairs the production of hemoglobin, leading to smaller and fewer red blood cells.

Symptoms

Fatigue and Weakness: Due to decreased oxygen delivery to tissues.

Pallor: Pale skin and mucous membranes from low hemoglobin levels.

Shortness of Breath: During exertion due to decreased oxygen-carrying capacity of blood.

Dizziness: Occasional dizziness or lightheadedness.

Pica: Craving non-food items like ice or dirt.

Diagnosis

Laboratory Tests:

Complete Blood Count (CBC): Low hemoglobin and hematocrit; low mean corpuscular volume (MCV).

Serum Ferritin: Low levels indicate depleted iron stores.

Serum Iron and TIBC: Low serum iron with high Total Iron-Binding Capacity (TIBC) confirms deficiency.

Treatment

Iron Supplements:

Oral ferrous sulfate or ferrous gluconate.

Dietary Changes: Increase intake of iron-rich foods.

Treat Underlying Causes: Address sources of chronic blood loss or malabsorption issues.

Prevention

Balanced Diet: Ensuring adequate dietary iron intake.

Regular Screening: For high-risk groups such as pregnant women and young children.

Embolism

Definition

An embolism is a blockage in a blood vessel caused by an embolus—a foreign substance or blood clot traveling from another part of the body.

Types of Embolism

1.Pulmonary Embolism

Definition: Obstruction of the pulmonary arteries usually by a blood clot from the deep veins of the legs (deep vein thrombosis).

Symptoms: Shortness of breath, chest pain, cough, hemoptysis.

Diagnosis:

CT pulmonary angiography, V/Q scan, or Doppler ultrasound of the legs.

Treatment: Anticoagulants, thrombolytics, and in severe cases, surgical embolectomy or catheter-directed therapy.

2.Cerebral Embolism

Definition:

An embolus traveling to the brain, causing a stroke.

Symptoms:

Sudden weakness, numbness, or difficulty speaking.

Diagnosis:

Brain imaging (CT or MRI) to identify stroke.

Treatment:

Anticoagulants, antiplatelet agents, thrombolysis.

3.Systemic Embolism

Definition:

An embolus traveling through the systemic circulation to organs or extremities.

Symptoms: Symptoms vary by organ affected, such as limb pain or organ dysfunction.

Diagnosis: Depends on the affected organ; imaging and physical examination.

Treatment: Anticoagulants, addressing the embolism’s source.

4.Fat Embolism

Definition:

Fat globules released into the bloodstream often after a fracture or trauma.

Symptoms: Fever, rash, respiratory distress.

Diagnosis: Clinical suspicion, imaging, and blood tests.

Treatment: Supportive care, managing the source of fat release.

5.Air Embolism

Definition: Air bubbles entering the bloodstream, often during medical procedures.

Symptoms: Chest pain, difficulty breathing, neurological symptoms.

Diagnosis: Clinical evaluation, imaging as necessary.

Treatment: Hyperbaric oxygen therapy, supportive care.

6.Septic Embolism

Definition: Emboli containing infectious agents, often from infective endocarditis.

Symptoms: Signs of sepsis and potential organ dysfunction.

Diagnosis: Blood cultures, imaging.

Treatment: Antibiotics, addressing the source of infection.

Risk Factors for Embolism

Immobility:

Prolonged periods of inactivity.

Recent Surgery or Trauma: Increases risk of clot formation.

Heart Conditions: Atrial fibrillation, heart valve disease.

Medical Conditions:

History of deep vein thrombosis, or other clotting disorders.

Prevention

Anticoagulants: For patients at high risk for embolism.

Lifestyle Changes:

Regular exercise and managing risk factors.

🔸e) Peptic Ulcer

Definition

A peptic ulcer is a sore that develops on the lining of the stomach, small intestine, or esophagus due to the erosion caused by stomach acids. It is a common gastrointestinal condition that affects the digestive tract.

Types of Peptic Ulcers

1.Gastric Ulcers

Location: Occur in the lining of the stomach.

Symptoms: Often cause pain shortly after eating.

2.Duodenal Ulcers

Location: Found in the upper part of the small intestine (duodenum).

Symptoms: Pain usually occurs a few hours after eating and may be relieved by eating or taking antacids.

3.Esophageal Ulcers

Location : Develop in the esophagus.

Symptoms: Cause pain during swallowing and may be associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

Causes

1.Helicobacter pylori Infection

Description:

A bacterium that colonizes the stomach lining and causes inflammation, leading to ulcer formation.

Mechanism: H. pylori damages the mucosal lining of the stomach and duodenum, increasing acid secretion and reducing mucosal protection.

2.Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

Description: Medications like aspirin, ibuprofen, and naproxen that reduce inflammation but can damage the gastric mucosa.

Mechanism: NSAIDs inhibit prostaglandin synthesis, which decreases mucus and bicarbonate production, weakening the gastric lining.

3.Excessive Alcohol Consumption

Description: Chronic alcohol intake can damage the gastric mucosa.

Mechanism: Alcohol increases gastric acid secretion and irritates the stomach lining.

4.Smoking

Description: Tobacco use exacerbates ulcer formation and delays healing.

Mechanism: Smoking increases acid secretion and impairs mucosal defenses.

5.Stress

Description: Physical and emotional stress can contribute to ulcer formation.

Mechanism: Stress may increase gastric acid secretion and reduce mucosal defenses.

6.Genetic Factors

Description: Family history of peptic ulcers may increase susceptibility.

Mechanism: Genetic predisposition can affect acid secretion and mucosal defense mechanisms.

Symptoms

Abdominal Pain: Burning or gnawing pain in the upper abdomen, often relieved by eating or taking antacids.

Nausea and Vomiting: Feeling sick to the stomach and vomiting, which may include blood.

Bloating: A sensation of fullness or swelling in the abdomen.

Loss of Appetite: Reduced desire to eat due to discomfort or pain.

Weight Loss: Unintentional weight loss due to decreased food intake.

Diagnosis

Endoscopy: A procedure where a flexible tube with a camera is inserted through the mouth to visualize the stomach and duodenum.

H. pylori Testing: Breath, stool, or blood tests to detect the presence of Helicobacter pylori infection.

Imaging: X-rays or upper gastrointestinal series with barium can be used to view ulcers.

Biopsy:

A small tissue sample taken during endoscopy for further examination.

Treatment

1.Medications

Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs): Reduce stomach acid production. Examples: omeprazole, esomeprazole.

H2-Receptor Antagonists: Decrease acid secretion. Examples: ranitidine, famotidine.

Antibiotics: Eradicate H. pylori infection. Examples: amoxicillin, clarithromycin.

Antacids: Neutralize stomach acid. Examples: magnesium hydroxide, aluminum hydroxide.

Cytoprotective Agents: Protect the gastric lining. Examples: sucralfate, misoprostol.

2.Lifestyle Modifications

Avoid NSAIDs: Use alternative pain relief methods.

Reduce Alcohol Intake: Limit or avoid alcohol consumption.

Quit Smoking: Stop tobacco use to improve healing.

Manage Stress: Implement stress-reduction techniques like meditation or exercise.

Prevention

H. pylori Screening: For individuals at high risk or with a history of ulcers.

Avoid Risk Factors: Reducing NSAID use, avoiding excessive alcohol, quitting smoking, and managing stress.

Healthy Diet: Consuming a balanced diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains.

Complications

Bleeding:

Can lead to anemia or require blood transfusions.

Perforation:

A hole in the wall of the stomach or duodenum causing severe abdominal pain.

Obstruction: Swelling or scarring can block the passage of food through the digestive tract.

Gastric Cancer: Long-term ulcers can increase the risk of stomach cancer.

Q-6. Write answer on followings:

🔸a) Auto Immune diseases

Autoimmune Diseases

Definition

Autoimmune diseases are conditions where the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks its own cells, tissues, or organs, leading to inflammation and damage.

Mechanism

The immune system normally distinguishes between self and non-self. In autoimmune diseases, this recognition fails, and the immune system targets normal cells as if they were foreign invaders. This failure can be triggered by genetic, environmental, or hormonal factors.

Examples and Symptoms

1.Rheumatoid Arthritis

Symptoms:

Joint pain, swelling, and stiffness.

2.Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE)

Symptoms: Fatigue, skin rashes, and joint pain.

3.Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus

Symptoms: Increased thirst, frequent urination, and weight loss.

4.Multiple Sclerosis

Symptoms: Muscle weakness, vision problems, and coordination issues.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis typically involves a combination of clinical evaluation and laboratory tests, including autoantibody panels (e.g., anti-CCP for rheumatoid arthritis) and imaging studies.

Treatment

Treatment focuses on reducing immune system activity and managing symptoms through medications like corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, and disease-modifying agents.

🔸b) Gene Therapy

Gene Therapy

Definition

Gene therapy is a medical technique aimed at treating or preventing diseases by altering the genetic material within a patient’s cells. It involves the introduction, removal, or modification of genetic material to correct defective genes or enhance cellular functions.

Mechanism

Gene therapy works by:

1.Gene Replacement

Method: Introducing a healthy copy of a gene to replace a defective or missing gene.

Example: Introducing a functional copy of the CFTR gene in cystic fibrosis.

2.Gene Editing

Method: Correcting mutations in a gene using technologies like CRISPR-Cas9.

Example:

Editing the DMD gene to correct mutations in Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

3.Gene Silencing

Method: Suppressing the activity of a harmful gene.

Example:

Using RNA interference to inhibit the expression of the oncogene in cancer.

4.Gene Augmentation

Method:

Adding a gene to enhance the function of existing cellular processes.

Example: Adding a gene to increase the production of a therapeutic protein.

Applications

1.Genetic Disorders

Example: Treatment of inherited conditions like SCID (Severe Combined Immunodeficiency) through the introduction of functional immune system genes.

2.Cancer Therapy

Example: Introducing genes that encode for proteins to trigger immune responses against cancer cells, such as CAR-T cell therapy.

3.Infectious Diseases

Example: Development of vaccines and therapies that introduce genetic material to provoke immune responses against pathogens like HIV.

4.Rare Diseases

Example: Correcting genetic mutations in diseases like hemophilia through the delivery of functional clotting factor genes.

Challenges

1.Safety Concerns

Risks include unintended effects like off-target mutations or immune responses against the introduced genes.

2.Delivery Methods

Efficiently delivering genetic material into the target cells using vectors like viruses or nanoparticles.

3.Ethical Issues

Concerns about potential long-term impacts and the ethical implications of editing the human germline

FOR MORE DETAILS KINDLY CONTACT US ON (CALL/WHATSAPP)-8485976407