01/09/2018-B.SC – NURSING FOUNDATION PAPER-PAPER SOLUTION NO.5

PAPER SOLUTION NO.5-01/09/2018

Section 1

Q.1 Define following (Any five) [10]

1. Rigor mortis

- Rigor mortis is the postmortem stiffening of the muscles that occurs after death due to chemical changes in the muscles, specifically the depletion of ATP (adenosine triphosphate), which is required for muscle relaxation.

- It Begins within 1–2 hours after death. It affects small muscles first (like eyelids, jaw) and later large muscles. It disappears after 24–48 hours as the body undergoes decomposition

2. Surgical asepsis

- Surgical asepsis, also known as sterile technique, is the complete elimination of all microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses, spores, and fungi, from an object or area to prevent infection during invasive procedures.

- Surgical asepsis is the practice of maintaining a sterile environment to prevent contamination by pathogens during surgical or invasive procedures.

3. Blood pressure

- Blood pressure is the force exerted by circulating blood on the walls of the arteries.

- It is an important vital sign and indicates how effectively the heart is pumping blood throughout the body. It is produced by the pumping action of the heart.

- Blood pressure is measured in millimeters of mercury (mmHg) and is expressed as systolic over diastolic pressure (e.g., 120/80 mmHg).

4. Disinfactant

- A disinfectant is a chemical agent used to destroy or inactivate harmful microorganisms (such as bacteria, viruses, and fungi) on non-living surfaces and objects, but not necessarily bacterial spores.

- It is used on inanimate objects like instruments, floors, tables. Common disinfectants include : Phenol, Chlorine, Alcohol, Glutaraldehyde

5. Cross infection

- Cross infection is the transmission of infection from one person to another, or from one part of the body to another, within a healthcare setting, usually due to lack of proper infection control practices.

- Examples : A patient with pneumonia spreading the infection to another patient through contaminated hands of a nurse.

6. Barrier nursing

- Barrier nursing is a method of infection control used to prevent the spread of infectious diseases by creating a protective barrier between the infected patient and others, including healthcare workers and visitors.

- It is used to minimize or prevent the transmission of pathogens through direct or indirect contact.

Q.2 Short notes on (Any three) [15]

1. Principles of body mechanisms

Body mechanics refers to the use of the body in an efficient and safe way to prevent injury, especially during activities like lifting, moving, or positioning patients. Applying proper body mechanics is essential in nursing, caregiving, and daily life to maintain postural alignment, reduce fatigue, and prevent musculoskeletal injuries.

1. Maintain a Wide Base of Support

- Keep feet shoulder-width apart or one foot slightly ahead of the other

- Improves balance and stability while standing or lifting

- Helps in withstanding unexpected shifts in weight

- Provides a firm foundation, especially when handling heavy loads or assisting patients

2. Use the Strongest and Largest Muscles

- Use leg and thigh muscles to lift, not the lower back

- Large muscles fatigue slower than smaller muscles

- Reduces the risk of injury, especially in the lumbar region

- Promotes efficiency and stability during movements

- Helps maintain endurance during repeated lifting tasks

3. Keep the Body Aligned and in Good Posture

- Maintain natural spinal curves (neck, back, lumbar)

- Avoid bending sideways or slouching

- Distribute weight evenly on both feet

- Enhances balance, prevents muscle fatigue

- Keeps core muscles engaged for support

4. Keep the Load Close to the Body

- Hold objects or patients near the waist or center of gravity

- Prevents excess strain on arms and back

- Offers better control and reduces the chance of dropping the object

- Keeps the weight balanced and reduces the force needed

5. Bend the Knees – Not the Waist

- Squatting down keeps the spine straight

- Allows you to use strong thigh muscles

- Reduces strain on the intervertebral discs

- Prevents lower back injuries commonly caused by bending improperly

6. Avoid Twisting Movements

- Twisting while lifting can damage the spine and muscles

- Move your feet and turn your whole body instead

- Keeps spinal column aligned and protected

- Especially important when transferring patients between bed and wheelchair

7. Push Rather Than Pull

- Pushing allows you to use your body weight and leg strength

- Pulling often causes back strain and imbalance

- Safer method when moving beds, trolleys, or wheelchairs

- Maintain a straight back and bend knees slightly while pushing

8. Use Smooth, Coordinated Movements

- Avoid sudden jerks or uncontrolled shifts

- Prevents muscle tears, sprains, and patient injury

- Ensures the movement is predictable and safe

- Boosts confidence of the patient being moved

9. Plan the Movement in Advance

- Check the weight, size, and path before lifting

- Remove clutter or obstacles from the area

- Inform the patient of the steps to be taken

- Ask for assistance or use mechanical aids if needed

- Prevents accidents due to poor preparation

10. Adjust the Working Height

- Raise beds or trolleys to a comfortable height for procedures

- Prevents overreaching and slouching

- Reduces fatigue in long-duration procedures (e.g., dressing changes)

- Ideal working height is usually at waist or elbow level

2. Health assessment

Health assessment is the systematic method of collecting and analyzing data about a patient’s physical, psychological, social, and spiritual health status. It is the foundation of nursing care, used to establish a baseline, identify health problems, and plan appropriate care.

Objectives of Health Assessment

- To establish a baseline for future comparisons

- To identify actual or potential health problems

- To evaluate patient responses to interventions

- To promote health, prevent illness, and detect diseases early

- To ensure holistic, patient-centered care

Types of Health Assessment

Comprehensive Health Assessment

- It is Performed on initial contact or admission

- It Includes complete health history and head-to-toe physical examination

- It is Useful for chronic illness, elderly, or new patients

Focused/Problem-Oriented Assessment

- It is Done when a specific health problem or symptom is present

- In which Focus on one body system or area of concern

- Example: Abdominal pain → focus on GI system

Ongoing/Follow-up Assessment

- It is Repeated at regular intervals to monitor progress or deterioration

- It is Used during hospitalization or after discharge

- Example: Monitoring BP in hypertensive patient

Emergency Assessment

- It is Rapid and specific, done in life-threatening situations

- In which Focus on Airway, Breathing, Circulation (ABC)

- It is Used in trauma, cardiac arrest, or unconscious patients

Components of Health Assessment

Health History Collection

The health history is the first component and involves gathering subjective information from the patient through a structured interview. It provides insight into the patient’s past and current health status, as well as factors influencing health. It includes :

- Biographical data (name, age, gender, occupation)

- Chief complaint

- Present illness history

- Past medical/surgical history

- Family history

- Lifestyle habits (diet, sleep, exercise, smoking)

- Psychosocial and cultural background

Physical Examination

The physical examination is the direct observation and measurement of the patient’s body to gather objective data. It is usually conducted from head to toe and follows a systematic approach to avoid missing any findings. The four basic techniques used in physical examination include :

- Inspection – visual observation

- Palpation – feeling body parts

- Percussion – tapping to assess structures

- Auscultation – listening with stethoscope

Mental Health Assessment

A mental health assessment evaluates the patient’s emotional, cognitive, and psychological functioning. This component is especially important in patients presenting with behavioral changes, confusion, or mood disturbances. It includes Appearance, behavior, Mood, thought processes, Orientation (person, place, time), Memory, attention, judgment

Nutritional Assessment

A nutritional assessment determines whether the patient’s dietary intake and nutritional status meet their body’s needs. It involves both subjective and objective data and is crucial in both health promotion and disease management.

Functional Assessment

The functional assessment evaluates the patient’s ability to perform Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) and maintain independence in daily life. This is especially significant in elderly, chronically ill, or disabled patients. Assesses ability to perform Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) like Eating, bathing, dressing, toileting, mobility

Importance of Health Assessment in Nursing

- Provides data for accurate nursing diagnosis

- Helps in individualized care planning

- Facilitates communication among healthcare team

- Promotes patient involvement and trust

- It supports in early detection and health promotion

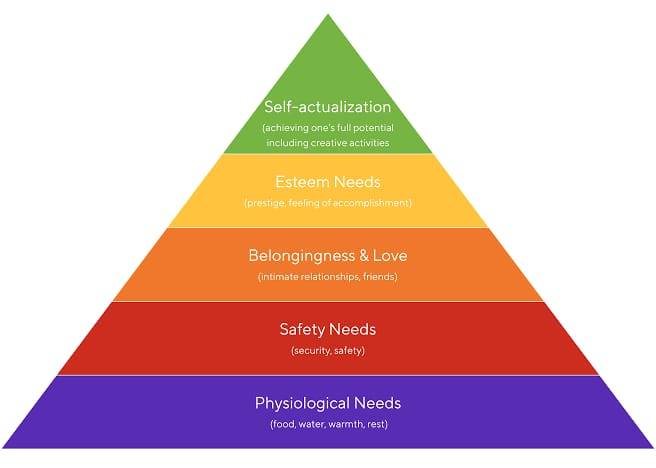

3. Maslow hierarchy theory

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs is a psychological theory developed by Abraham Maslow in 1943, which suggests that human needs are arranged in a hierarchy, starting from the most basic physical needs to more complex psychological and self-fulfillment needs. The theory proposes that lower-level needs must be satisfied before a person can focus on higher-level growth.

1. Physiological Needs

- These are the basic biological requirements essential to human survival. Without fulfilling these, the body cannot function properly.

- These include air, water, food, shelter, rest, elimination, and temperature regulation.

- If these needs are not met, the body goes into survival mode.

- These are priority needs in critical care or emergencies.

2. Safety and Security Needs

- Once physiological needs are met, people desire safety, stability, and protection from harm.

- Includes physical safety (free from accidents or injury)

- Also includes emotional security (freedom from fear or anxiety)

- Stability of job, health, routine, and law & order are also part of this level

3. Love and Belongingness Needs

- After safety is secured, humans naturally seek emotional connections and social belonging.

- Involves friendship, intimacy, family bonding, and acceptance in groups

- Lack of love or belonging leads to loneliness, depression, or anxiety

4. Esteem Needs

- These relate to a person’s self-respect and the respect they receive from others.

- Includes confidence, recognition, independence, and achievements

- There are two types :

- Self-esteem (inner confidence, competence)

- Esteem from others (appreciation, acknowledgment)

5. Self-Actualization Needs

- This is the highest level, where a person aims to reach their full potential and seeks growth, purpose, and fulfillment.

- Focus on creativity, morality, purpose of life, spirituality, and personal development

- People at this level are motivated by values and purpose

- These needs vary for each individual

4. Ethical issue in nursing

Ethical issues in nursing refer to situations where nurses face moral conflicts about what is the “right” or “best” action to take, especially when values, rights, duties, or patient care needs come into conflict. These issues arise in everyday practice and require nurses to balance professional standards, legal responsibilities, and patient rights.

Informed consent

- Nurses must ensure that consent is voluntary and not coerced, even by family members or physicians.

- In emergencies, implied consent may be applied but must be documented carefully.

- Example : A patient with dementia is scheduled for surgery — the nurse must ensure a legally authorized person signs consent.

- Patient Autonomy vs. Paternalism

Autonomy is the right of a patient to make their own healthcare decisions, even if those decisions seem risky. - Paternalism occurs when a healthcare provider overrides patient wishes to protect them from harm, thinking “we know best”.

- Nurses must educate without pressuring, guiding patients while respecting their values.

- Example : A diabetic patient refuses insulin due to fear of needles — the nurse must honor the choice while addressing misconceptions empathetically.

- Confidentiality and Privacy

Patient confidentiality means keeping personal health information secure and disclosing it only with permission. - Ethical breaches may occur when nurses discuss patient details in public areas or post on social media.

- Nurses must balance confidentiality with legal duties (e.g., reporting child abuse or notifiable diseases).

- Example : A nurse accidentally shares HIV status in a semi-private ward — this breach could cause social stigma and emotional trauma.

- End-of-Life Care / Euthanasia

In end-of-life care, nurses often face ethical issues like Do-Not-Resuscitate (DNR) orders, withdrawal of life support, or palliative sedation. - In some countries, euthanasia or assisted dying is legally permitted but ethically controversial.

- Nurses must support patient dignity and comfort, even when curative treatment stops.

- Example : A family insists on keeping a ventilator running against a terminal patient’s DNR wishes — the nurse is caught between emotional distress and ethical duty.

- Allocation of Scarce Resources

When resources like ICU beds, oxygen, or staff are limited (e.g., during pandemics), difficult choices must be made. - Nurses may face moral distress when forced to prioritize care based on survival likelihood or institutional policy.

- Ethical principles like justice (fairness) and beneficence (doing good) must guide decisions.

- Example: Choosing between two critical patients for one ventilator during COVID-19—nurses must advocate but cannot override triage protocols.

- Truth-Telling vs. Withholding Information

Nurses must be honest and transparent with patients about diagnoses and outcomes. - Families sometimes request nurses to hide bad news to protect the patient emotionally.

- Ethically, the nurse must respect the patient’s right to know while considering emotional readiness.

- Example: A daughter asks the nurse not to tell her father he has cancer — the nurse must encourage open communication while respecting both sides.

- Cultural and Religious Belifs

Patients may refuse treatments (like blood transfusions or surgery) due to religious or cultural beliefs. - Nurses must respect diversity while educating about consequences of refusal.

- Ethnocentrism (judging other cultures) must be avoided in care decisions.

- Example : A Jehovah’s Witness patient declines blood transfusion even during surgery — the nurse must advocate for blood alternatives and patient autonomy.

- Professional Boundaries and Relationships

Nurses must maintain professional relationships with patients and avoid emotional dependence, favoritism, or romantic involvement. - Accepting gifts, favors, or forming personal attachments can compromise objectivity and patient care.

- Boundary violations can lead to loss of license, legal action, and patient harm.

- Example : A nurse regularly texts and visits a former patient after discharge — this may breach professional conduct standards.

- Refusal to Provide Care (Conscientious Objection)

Nurses may ethically object to procedures like abortion, euthanasia, or gender reassignment due to personal/religious beliefs. - However, they must not abandon patients and must ensure that care is passed on to another qualified provider.

- Ethical frameworks and institutional policies must guide these decisions.

- Example : A nurse refuses to assist in an abortion but ensures another staff member continues care — this balances personal ethics with professional responsibility.

- Whistleblowing / Reporting Unsafe Practice

When nurses witness negligence, abuse, or unsafe practices, they have an ethical obligation to report — even if it involves a colleague or superior. - This may cause conflict, retaliation, or emotional burden, but patient safety comes first.

- Institutions must protect whistleblowers under ethical and legal frameworks.

- Example : A nurse reports a colleague repeatedly giving wrong insulin doses — though difficult, this protects patient lives.

Q.3 Elaborate on (13)marks

a. Define health (2)

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 1948 “Health is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”

b. What are the various factor influencing health (3)

Health is influenced by a wide range of biological, environmental, social, and behavioral factors. These factors work together to determine the health status of an individual or population.

Biological Factors

- These are genetic and physiological elements that a person is born with or acquires :

- Heredity (inherited diseases like diabetes, hypertension)

- Age (older age can increase disease risk)

- Gender (certain diseases are gender-specific)

- Immunity status (natural or acquired immunity)

- Nutritional status

Environmental Factors

- The physical and chemical surroundings that affect a person’s health:

- Clean water and air

- Sanitation and hygiene

- Housing conditions

- Pollution (air, water, noise)

- Climate and weather conditions

Lifestyle and Behavioral Factors

- These are habits and actions that impact health :

- Diet and nutrition

- Physical activity

- Smoking, alcohol, or drug use

- Sleep patterns

- Stress and coping mechanisms

Social and Economic Factors

- Also known as social determinants of health :

- Education level

- Employment and income

- Social support systems

- Cultural practices and beliefs

- Access to health care services

Health Services and System Factors

- Availability and accessibility of medical care

- Quality of care provided

- Health insurance and affordability

- Preventive and promotive services

- Health education and awareness

Psychological Factors

- Mental health conditions

- Self-esteem and emotional resilience

- Perception of health and illness

- Political and Policy Factors

- Health-related laws and policies

- Government health programs

- Regulation of drugs and food

- Public health campaigns

c. Explain the impact of illness on patient and family (8)

Illness affects not only the individual patient but also their family physically, emotionally, socially, and economically. The degree of impact depends on the severity, duration, prognosis, and type of illness (acute or chronic).

1. Impact on the Patient

Illness affects the entire well-being of an individual, not just their physical body. It interferes with a person’s normal functioning, independence, emotions, roles, relationships, and even their sense of identity. The impact may vary depending on whether the illness is acute, chronic, progressive, or terminal.

a) Physical Impact

- The patient’s daily functioning may be limited by symptoms like pain, fatigue, breathlessness, or paralysis.

- It can limit the patient’s ability to perform daily activities such as eating, dressing, walking, or bathing.

- Conditions like stroke, fractures, or cancer can lead to loss of independence, requiring help for simple tasks like eating or bathing.

- Long-term bed rest may lead to complications such as bed sores, muscle wasting, or infections.

- Prolonged immobility can result in bedsores, infections, or muscle wasting.

b) Psychological and Emotional Impact

- Patients often go through emotional stages such as denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance (Kübler-Ross model).

- They may experience fear of death, loss of dignity, or anxiety about body image changes (e.g., in breast cancer or amputations).

- Depression, guilt, and suicidal thoughts are common in chronic diseases or disabilities.

- Changes in body image (e.g., amputation, surgery scars) can affect self-esteem.

- c) Social Impact

- Illness may lead to social isolation due to inability to participate in social life.

- Patients with infectious diseases or mental illness may experience stigma and discrimination.

- Long hospital stays or frequent doctor visits reduce social contact and personal interaction.

d) Economic Impact

- The patient may be unable to continue work, losing income.

- Treatment costs (e.g., dialysis, chemotherapy, surgeries) can be extremely expensive.

- They may become financially dependent on others or need government aid or insurance.

e) Occupational and Educational Impact

- Many patients are unable to continue work or studies, affecting productivity.

- Loss of employment can lead to financial stress and identity loss.

- They may also lose access to health insurance or retirement benefits.

Spiritual and Existential Impact

- Some patients question their faith or beliefs, especially when suffering is intense.

- Illness may lead to a spiritual crisis or search for deeper meaning and inner peace.

- Patients might express desire for spiritual guidance, prayer, or rituals.

2. Impact on the Family

a) Emotional & Psychological Impact

- Family members, especially caregivers, may suffer from constant stress, anxiety, and helplessness.

- Parents of sick children may feel guilt, while spouses of terminal patients face emotional breakdowns.

- Fear of losing a loved one can cause insomnia, depression, or irritability.

b) Role Strain and Changes

- The family structure often shifts—children take on adult roles, spouses become full-time caregivers.

- For example, in a family where the father is bedridden, the mother may become the sole provider and decision-maker.

- This leads to role conflicts, stress, and sometimes domestic tension.

c) Social Life Disruption

- Caregivers may withdraw from community functions, festivals, or outings due to patient care needs.

- Children’s schooling may be affected as they may miss school to help at home.

- Family celebrations or plans may be postponed or canceled due to ongoing illness.

d) Financial Burden

- High treatment costs can exhaust family savings or lead to borrowing and debt.

- One or more family members may have to leave their jobs to provide care.

- Travel expenses, diagnostic tests, medications, and nutritional needs add to the cost.

e) Caregiver Burden

- Primary caregivers often suffer from physical fatigue, backache, or sleep deprivation.

- They may neglect their own health, increasing their risk of developing illness.

- The emotional toll may lead to burnout, which is common in chronic care.

f) Impact on Children

- Children may feel neglected or confused about the family changes.

- They may fall behind in studies or develop behavioral issues.

- Long-term illness in a sibling or parent can cause children to mature prematurely or suffer emotional trauma.

Impact on Family’s Mental Health

- Risk of generalized anxiety disorder, depression

- Family members needing counseling or psychiatric help

- PTSD in families after witnessing ICU care, surgeries, or palliative care

Section 2

Q.4 Short answer on (Any five) [10 marks]

1. Immobility

Immobility refers to a state in which an individual is unable to move freely or independently, either partially or completely, due to illness, injury, or physical limitation, leading to potential complications in multiple body systems.

2. Communication

Communication is the process of exchanging information, ideas, thoughts, or feelings between two or more individuals through verbal, non-verbal, written, or symbolic methods, to achieve mutual understanding and response.

3. Hyperthermia

Hyperthermia is a condition in which the body temperature rises above the normal range (usually > 38°C or 100.4°F) due to the body’s inability to dissipate heat, often caused by external heat exposure, illness, or reduced thermoregulation.

4. Nursing as a profession

Nursing as a profession is a scientific and humanistic discipline that involves the assessment, planning, implementation, and evaluation of care to individuals, families, and communities, aimed at promoting health, preventing illness, restoring health, and alleviating suffering. It is guided by ethical principles, evidence-based practice, and requires formal education, specialized knowledge, and continuous professional development.

5. Autopsy

Autopsy is a systematic post-mortem examination of a body performed by a pathologist to determine the cause of death, identify disease or injury, and evaluate any medical or legal issues related to the death.

6. Nursing process

The nursing process is a systematic, scientific, and dynamic method used by nurses to assess, plan, implement, and evaluate individualized care for patients, aiming to meet their physical, emotional, psychological, and social needs. It consisting of five steps: assessment, diagnosis, planning, implementation, and evaluation.

Q.5 Short notes on (any three) [15 marks]

1. Biomedical waste management

Definition

Biomedical waste refers to any waste generated during diagnosis, treatment, or immunization of human beings or animals, or in research activities related to biological production or testing, which may be infectious, hazardous, or toxic to health and the environment.

Objectives of Biomedical Waste Management

- To prevent infection and injury to healthcare workers, patients, and the community.

- To ensure safe handling, segregation, transportation, and disposal of biomedical waste.

- To protect the environment from contamination by hazardous biomedical materials.

- To comply with national laws, regulations, and health standards (e.g., BMW Rules 2016).

- To reduce the risk of transmission of diseases such as HIV, Hepatitis B, and C.

- To promote recycling and recovery of materials wherever safe and possible.

- To encourage accountability and responsibility among healthcare staff for waste disposal.

- To minimize waste generation by promoting judicious use of materials and resources.

Categories of Biomedical Waste

1️⃣ Yellow Category

- It includes human and animal anatomical waste, soiled dressings, microbiology lab waste, and expired medicines.

- It is Highly infectious and non-recyclable waste.

- Disposal: Incineration, plasma pyrolysis, or deep burial.

2️⃣ Red Category

- It includes contaminated recyclable waste like IV sets, catheters, Urine bags, gloves, syringes (without needles), Blood bags (if recyclable).

- It is Recyclable after disinfection and shredding.

- Disposal: Autoclaving, microwaving, or chemical treatment, followed by shredding and recycling.

3️⃣ White (Translucent) Category

- It includes sharps such as needles, scalpels, blades, syringes with fixed needles.

- It Must be handled with extreme care to prevent injuries and infection.

- Disposal: Collected in puncture-proof containers, then autoclaved or dry-heat sterilized and shredded/encapsulated.

4️⃣ Blue Category

- It includes broken glass, medicine vials, ampoules, and contaminated glassware.

- Non-infectious but hazardous if not handled properly.

- Disposal: Disinfection (chemical/autoclave), then recycling.

Steps in Biomedical Waste Management (BMWM)

1️⃣ Segregation at Source

Biomedical waste must be segregated immediately at the point of generation, such as operation theatres, wards, or laboratories, into appropriate color-coded containers based on the category of waste, to prevent mixing and ensure safe disposal.

2️⃣ Collection of Waste

The segregated waste is then collected in leak-proof, labeled bags or containers, using trolleys or bins that are covered and easy to clean, ensuring minimal handling and no spillage or leakage during the collection process.

3️⃣ Storage of Biomedical Waste

Collected waste should be stored temporarily in a designated, secure storage area within the hospital, which is well-ventilated, away from patient care areas, and the storage period should not exceed 48 hours under any circumstances.

4️⃣ Transportation (Internal and External)

Waste is transported internally to the storage area using closed containers or trolleys, and externally to a Common Biomedical Waste Treatment Facility (CBWTF) using authorized, GPS-tracked vehicles that are designed to prevent leakage or contamination.

5️⃣ Treatment of Waste

Biomedical waste is treated according to its category using methods such as incineration, autoclaving, microwaving, shredding, or chemical disinfection, depending on whether the waste is infectious, sharps, or recyclable.

6️⃣ Final Disposal

After treatment, waste is safely disposed of—incineration ash is sent to secured landfills, sharps are encapsulated, recyclable plastics are sent for reprocessing, and hazardous residues are handled as per environmental guidelines.

7️⃣ Record Keeping and Documentation

Healthcare facilities must maintain proper records of the quantity of waste generated, treated, and handed over to the CBWTF, along with treatment logs, barcoding records, and manifest copies as per government regulations.

8️⃣ Training and Monitoring

Regular training of healthcare workers and housekeeping staff on biomedical waste management protocols is essential, along with audits and inspections to ensure compliance with BMW rules and prevent healthcare-associated infections.

2. Routes of medication administration

1️⃣ Oral Route (PO):

In this method, the medication is swallowed by mouth and absorbed through the gastrointestinal tract. It is the most common, convenient, and economical route, but it has a slower onset of action and may be affected by food, gastric pH, or first-pass metabolism.

Example: Paracetamol tablets, Iron supplements.

2️⃣ Sublingual Route:

The drug is placed under the tongue and allowed to dissolve, enabling rapid absorption directly into the bloodstream through the sublingual mucosa, bypassing the digestive system and first-pass liver metabolism.

Example: Nitroglycerin tablets for angina.

3️⃣ Buccal Route:

Medication is placed between the cheek and gums where it dissolves and is absorbed through the buccal mucosa, offering faster action and bypassing the GI tract.

Example: Buccal tablets of hormones or painkillers.

4️⃣ Topical Route:

Drugs are applied directly to the skin or mucous membranes for local effect, such as treating skin conditions, infections, or inflammation.

Example: Antifungal creams, steroid ointments.

5️⃣ Transdermal Route:

Medication is absorbed through the skin into the systemic circulation via a patch, providing sustained release over time.

Example: Nicotine patch, fentanyl patch.

6️⃣ Inhalation Route:

Drugs are inhaled in the form of gases, vapors, or aerosols into the lungs, where they are absorbed through the alveolar-capillary network, offering rapid onset and localized or systemic effect.

Example: Salbutamol inhaler for asthma, oxygen therapy.

7️⃣ Nasal Route:

Medications are sprayed or instilled into the nasal cavity, allowing quick absorption through the nasal mucosa, often for local (decongestants) or systemic effects (hormones, vaccines).

Example: Nasal decongestant sprays, COVID-19 nasal vaccines.

8️⃣ Ophthalmic Route:

Drugs are instilled as eye drops or ointments for local action in treating infections, inflammation, or glaucoma.

Example: Antibiotic eye drops, anti-glaucoma agents.

9️⃣ Otic Route

Medications are placed into the ear canal to treat external or middle ear infections and remove wax.

Example: Ear drops for otitis externa.

🔟 Rectal Route

Drugs are inserted into the rectum in the form of suppositories or enemas and absorbed through the rectal mucosa. Useful when oral administration is not possible (e.g., vomiting).

Example: Paracetamol suppositories, glycerin suppositories.

1️⃣1️⃣ Vaginal Route

Medications such as creams, gels, or suppositories are inserted into the vagina for local effects such as treating infections or dryness.

Example: Antifungal vaginal tablets, estrogen creams.

1️⃣2️⃣ Subcutaneous (SC) Route

Medication is injected into the fatty tissue just under the skin, usually in the arm, thigh, or abdomen, for slow and sustained absorption.

Example: Insulin, heparin.

1️⃣3️⃣ Intramuscular (IM) Route

Medication is injected deep into a muscle (usually deltoid, gluteal, or vastus lateralis), where it is absorbed quickly into the bloodstream.

Example: Vaccines, analgesics like diclofenac.

1️⃣4️⃣ Intravenous (IV) Route

Drugs are injected directly into a vein, providing immediate and 100% bioavailability, ideal for emergencies and precise dosing.

Example: IV fluids, antibiotics, chemotherapy.

1️⃣5️⃣ Intradermal (ID) Route

Small amounts of drug are injected into the dermal layer of skin, commonly used for sensitivity tests or vaccines.

Example: Mantoux test for TB, allergy testing.

3. Hospital acquired infection

Definition

Hospital Acquired Infection (HAI) refers to any infection that a patient develops after 48 hours of hospital admission, which was not present or incubating at the time of admission. It may also appear after discharge but is related to hospital exposure.

Causative organisms

- MRSA – Surgical site, blood infections

- E. coli – Urinary tract infections

- Pseudomonas – Pneumonia, wound infections

- Klebsiella – Pneumonia, sepsis

- Acinetobacter – ICU infections

- VRE – Urinary and wound infections

- C. difficile – Diarrhea, colitis

- Candida – Fungal bloodstream infections

- Coagulase-negative Staph – Line infections

- Norovirus – GI outbreaks

Types of Hospital Acquired Infections (HAIs)

1️⃣ Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infection (CAUTI)

Catheter-associated urinary tract infection is a common hospital-acquired infection that occurs when bacteria enter the urinary tract through a urinary catheter, especially when it is inserted without strict aseptic precautions or left in place for a prolonged period, leading to symptoms such as dysuria, fever, and suprapubic discomfort.

2️⃣ Surgical Site Infection (SSI)

A surgical site infection is an infection that develops at or near the site of a surgical incision within 30 days after an operation, or up to 90 days if a prosthetic device is implanted, and usually results from contamination during surgery, poor hand hygiene, or improper wound care.

3️⃣ Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia (VAP)

Ventilator-associated pneumonia is a serious infection that occurs in patients who are on mechanical ventilation for more than 48 hours and is caused by the entry of pathogenic organisms into the lower respiratory tract through the endotracheal tube, often due to improper suctioning, poor oral hygiene, or colonized ventilator circuits.

4️⃣ Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infection (CLABSI)

A central line-associated bloodstream infection arises when microorganisms enter the bloodstream through a central venous catheter, typically because of improper insertion technique, lack of aseptic care during maintenance, or prolonged catheter use, leading to systemic signs of infection such as fever and chills.

5️⃣ Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia (Non-Ventilated)

Hospital-acquired pneumonia occurs 48 hours or more after a patient’s admission and is not related to ventilator use; it is typically caused by aspiration of oropharyngeal secretions, poor pulmonary hygiene, or impaired immunity, resulting in cough, fever, dyspnea, and abnormal chest X-rays.

6️⃣ Clostridium difficile Infection (CDI)

Clostridium difficile infection is a gastrointestinal infection characterized by watery diarrhea, abdominal pain, and fever, and it usually develops in hospitalized patients who have received prolonged or broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy, which disrupts the normal intestinal flora and allows overgrowth of C. difficile bacteria.

7️⃣ Peripheral Line-Associated Bloodstream Infection

This type of bloodstream infection can result from contamination of peripheral intravenous cannulas due to poor insertion technique, inadequate site disinfection, or failure to change IV lines at recommended intervals, leading to local signs such as redness or swelling and systemic symptoms like fever and hypotension.

8️⃣ Gastrointestinal Viral Infections (e.g., Norovirus)

Viral infections such as norovirus or rotavirus may spread in hospitals through contact with contaminated food, water, hands, or surfaces, and they cause acute onset of diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and fever, especially in immunocompromised or elderly patients.

9️⃣ Skin and Soft Tissue Infections (e.g., MRSA)

Skin and soft tissue infections like those caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) can develop in hospital settings, particularly in surgical wounds, bedsores, or IV insertion sites, due to colonization with resistant bacteria and poor skin care or hygiene practices.

Prevention of Hospital Acquired Infections (HAIs)

- Perform strict hand hygiene before and after patient contact.

- Use appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE).

- Follow aseptic technique during all invasive procedures.

- Sterilize and disinfect all reusable equipment properly.

- Clean and disinfect hospital surfaces regularly.

- Isolate infected or colonized patients as needed.

- Use antibiotics judiciously to prevent resistance.

- Handle catheters, IV lines, and ventilators with care.

- Keep patients and healthcare workers vaccinated.

- Educate and train staff on infection control practices.

- Screen patients on admission for drug-resistant organisms.

- Use dedicated equipment for isolated patients.

- Maintain proper waste disposal and biomedical waste protocols.

- Ensure adequate ventilation in patient care areas.

- Encourage early mobilization to prevent respiratory infections.

- Regularly monitor and audit infection control practices.

4. Types of fever

Fever is an elevation of body temperature above the normal range (usually >38°C or >100.4°F), caused by a disturbance in the hypothalamic thermoregulatory center, usually in response to infection, inflammation, malignancy, or autoimmune disorders.

Types of Fever (Based on Temperature Pattern)

- Continuous Fever:

In continuous fever, the body temperature remains elevated above the normal range throughout the day and does not vary by more than 1°C (1.8°F) in 24 hours. There are no periods when the temperature returns to normal, and the fever is sustained. This type of fever is typically observed in conditions like typhoid fever, urinary tract infections, and lobar pneumonia. - Remittent Fever:

In remittent fever, the body temperature remains persistently high throughout the day but shows marked fluctuations — usually more than 1°C — and never returns to normal within 24 hours. This type is often seen in infective endocarditis and rheumatic fever. - Intermittent Fever:

In this pattern, the fever rises for a few hours during the day and then returns to normal or below normal, often seen in cyclic infections. The person remains afebrile between febrile episodes. Common causes include malaria, sepsis, and tuberculosis. - Relapsing (Recurrent) Fever:

In relapsing fever, there are episodes of fever that last a few days followed by periods of normal temperature, and then the fever returns after a few days. The pattern repeats multiple times. This occurs in diseases like louse-borne relapsing fever caused by Borrelia. - Septic Fever:

Septic fever is an irregular type of fever with wide fluctuations, chills, rigors, and sweating due to the presence of pathogenic bacteria in the bloodstream. This is seen in septicemia and severe systemic infections. - Pel-Ebstein Fever:

This is a rare cyclical fever pattern seen especially in Hodgkin’s lymphoma, where the person has 3 to 10 days of fever followed by 3 to 10 days of afebrile (normal temperature) period, and then the cycle repeats. - Hectic Fever:

It is a type of intermittent fever with very high daily temperature spikes, followed by rapid normalization with profuse sweating. The fluctuations are usually extreme. Classically seen in tuberculosis and suppurative infections.

Types of Fever (Based on Duration)

- Acute Fever:

This fever lasts less than 7 days and is most commonly caused by viral infections, flu, or the common cold. - Subacute Fever:

A fever that persists for 7 to 14 days, typically due to subacute bacterial infections or viral illnesses like dengue or typhoid in the early stages. - Chronic or Persistent Fever:

When the fever lasts for more than 14 days, it is termed chronic or persistent. It may be associated with tuberculosis, endocarditis, malignancies, or autoimmune diseases.

Special Named Fever Patterns

- Undulant Fever:

Seen in brucellosis, this fever rises and falls in a wave-like pattern, gradually increasing and decreasing over days. - Saddleback Fever:

A biphasic fever pattern where fever initially subsides and then reappears after a short afebrile interval, most commonly seen in dengue fever. - Drug-Induced Fever:

This occurs due to hypersensitivity or reaction to certain medications like antibiotics or anticonvulsants. The fever resolves after stopping the offending drug. - Neutropenic Fever:

This is a medical emergency in patients with very low neutrophil counts, commonly due to chemotherapy. Even a mild fever may indicate a life-threatening infection.

Q.6 Elaborate on [12 marks]

a. List the princiles related to oxygen administration (2 mark)

- Oxygen is a drug and must be prescribed.

- Maintain correct flow rate and concentration.

- Assess the patient before, during, and after administration.

- Use appropriate delivery device as per the patient’s need.

- Always humidify oxygen if flow is above 4 L/min.

- Ensure proper fit and placement of the device.

- Avoid open flames and flammable materials near oxygen sources.

- Observe for signs of oxygen toxicity.

- Monitor oxygen saturation (SpO₂) with a pulse oximeter.

- Educate the patient and family.

- Check oxygen equipment regularly for functionality and leakage.

- Ensure uninterrupted oxygen supply (check cylinder levels or concentrator function).

- Position the patient in semi-Fowler’s or high-Fowler’s position to improve ventilation.

- Use sterile water in humidifiers to prevent infection.

- Avoid excessive oxygen in COPD patients to prevent CO₂ retention.

b. Explain the methods of oxygen administration and nursing responsibilities (8 mark)

Method of oxygen administration

- Nasal Cannula (Nasal Prongs):

This is a simple, low-flow delivery system consisting of two soft prongs inserted into the nostrils, delivering 24–44% oxygen at 1–6 L/min; it allows the patient to speak, eat, and drink comfortably. - Simple Face Mask:

This mask covers the nose and mouth and provides 40–60% oxygen at 6–10 L/min; it is used for short-term oxygen therapy when higher concentrations are needed than nasal cannula can provide. - Venturi Mask:

A high-precision device that delivers a fixed, accurate concentration of oxygen (24% to 50%) by mixing oxygen with room air; it is commonly used for COPD patients who require controlled oxygen delivery. - Partial Rebreather Mask:

This mask includes a reservoir bag and allows the patient to rebreathe some exhaled air, providing 60–80% oxygen at 6–10 L/min; it is used in moderate hypoxia. - Non-Rebreather Mask (NRBM):

It delivers the highest oxygen concentration (up to 95–100%) at 10–15 L/min without rebreathing exhaled air, using a one-way valve between the mask and the reservoir bag; it is used in emergency or critically ill patients. - Face Tent:

A loose-fitting mask that provides 30–50% oxygen with humidification; used for patients with facial surgery, burns, or trauma where masks or nasal cannula can’t be applied. - Tracheostomy Collar (or Mask):

This is a device placed over a tracheostomy opening, delivering humidified oxygen directly into the trachea, typically used in tracheostomized or ventilated patients. - Oxygen Hood:

A plastic dome or box that fits over the infant’s head to deliver up to 80–90% oxygen; it is commonly used in neonatal care for infants requiring controlled oxygen environments. - Oxygen Tent:

A large plastic canopy that surrounds the patient, especially children, delivering humidified oxygen and maintaining temperature control; rarely used today due to poor seal and inefficiency. - High-Flow Nasal Cannula (HFNC):

This advanced device delivers heated and humidified oxygen at high flow rates (up to 60 L/min) through wide-bore nasal prongs; it is beneficial for moderate-to-severe respiratory distress. - Mechanical Ventilator (via ET or Tracheostomy Tube):

In severely ill or unconscious patients, oxygen is delivered under positive pressure through an endotracheal or tracheostomy tube, ensuring precise control of oxygen, respiratory rate, and pressure settings. - Transtracheal Oxygen Delivery:

A catheter is surgically placed directly into the trachea, allowing long-term, low-flow oxygen delivery in ambulatory patients, improving mobility and appearance compared to external devices.

Nursing Responsibilities During Oxygen Administration

- Verify the Physician’s Order:

The nurse must ensure a valid doctor’s prescription is available, specifying the flow rate (L/min), method of delivery (e.g., nasal cannula, mask), and duration of therapy. Any discrepancies or unclear orders must be clarified before starting. - Assess Patient’s Respiratory Status:

Before initiating oxygen, assess respiratory rate, depth, rhythm, use of accessory muscles, level of consciousness, skin color (cyanosis), and oxygen saturation (SpO₂) using a pulse oximeter. This provides a baseline for comparison. - Select and Prepare the Appropriate Oxygen Delivery Device:

Choose the most suitable oxygen delivery method based on the patient’s clinical condition, oxygen requirement, age, and comfort. Ensure the device is clean, intact, and functioning before use. - Maintain Oxygen Flow Rate as Prescribed:

Accurately set the flow meter according to the prescribed rate. Excess oxygen can lead to toxicity, especially in COPD patients, and insufficient oxygen can worsen hypoxia. - Humidify Oxygen if Needed:

If the flow rate is above 4 L/min, connect a humidifier to prevent drying of the nasal and oral mucosa, which can cause irritation, bleeding, and discomfort. - Ensure Proper Application and Comfort:

Apply the oxygen device securely and check frequently for pressure areas on the nose, ears, or cheeks. Reposition straps or apply soft padding to prevent skin breakdown. - Monitor Vital Signs and SpO₂ Continuously:

Observe and record temperature, pulse, respiration, blood pressure, and SpO₂ at regular intervals. If there is no improvement or saturation drops, notify the physician immediately. - Observe for Complications:

Be vigilant for signs of oxygen toxicity (restlessness, chest pain, dyspnea), hypoventilation, dryness of mucosa, headache, or CO₂ retention in COPD patients. Respond promptly and adjust therapy as needed. - Maintain Fire and Electrical Safety:

Post “No Smoking” signs, ensure no use of alcohol-based solutions, electrical sparks, or flames near the oxygen source. Oxygen accelerates combustion. - Check and Maintain Equipment Functionality:

Ensure oxygen cylinders or concentrators are functional and adequately filled. Inspect for leaks or faulty connections, and replace defective equipment immediately. - Document Therapy Details:

Accurately record the type of device used, flow rate, duration of administration, oxygen saturation levels, and patient’s response in the nursing records. - Educate the Patient and Family:

Explain the purpose of oxygen therapy, safe use at home (if discharged on oxygen), how to avoid hazards, and the importance of not adjusting flow without medical advice. - Provide Psychological Support:

Oxygen masks and tubing may cause anxiety or fear. Reassure the patient and encourage slow, relaxed breathing to help them feel comfortable.

c. Discuss the complication of oxygen administration (2 mark)

- Oxygen Toxicity:

Prolonged administration of high concentrations of oxygen (especially >60% for more than 24–48 hours) can lead to cellular damage in lung tissues, causing inflammation, pulmonary edema, and in severe cases, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). - Retinopathy of Prematurity (ROP):

In premature infants, excessive oxygen levels can lead to abnormal blood vessel growth in the retina, resulting in permanent vision impairment or blindness. - Absorption Atelectasis:

High concentrations of oxygen can wash out nitrogen from alveoli, leading to alveolar collapse as oxygen is rapidly absorbed, especially in areas of poor ventilation. - CO₂ Narcosis in COPD Patients:

In patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), excessive oxygen can suppress their hypoxic respiratory drive, leading to carbon dioxide retention (hypercapnia), drowsiness, and even coma. - Drying of Mucous Membranes:

Oxygen delivered without humidification can cause dryness and irritation of nasal and oral mucosa, leading to discomfort, bleeding, or infection. - Fire Hazard:

Oxygen supports combustion and creates a high risk of fire, especially in the presence of oils, greases, or flammable substances. Strict precautions are required during administration. - Barotrauma:

In mechanically ventilated patients receiving oxygen, high airway pressures can cause alveolar rupture, resulting in pneumothorax or subcutaneous emphysema. - Infection Risk:

Oxygen delivery devices (like nasal cannulas, masks, humidifiers) that are not properly cleaned or changed can harbor bacteria, leading to nosocomial respiratory infections. - Decreased Cardiac Output:

In some cases, especially with hyperoxia, there can be vasoconstriction of coronary arteries, potentially decreasing oxygen delivery to cardiac tissue.