P.B.B.Sc.(F.Y)-2016-BIOCHEM BIOPHYSICS (PAPER NO.1)(UPLOAD)(DONE)

P.B.B.Sc.(F.Y)-2016-BIOCHEM BIOPHYSICS (SAURASHTRA UNIVERSITY)(PAPER NO.1)

SECTION – I (BIOCHEMISTRY) (38 Marks)

1 LONG ESSAY: (ANY TWO) 2×10=20

(1) Give a detailed note on Glycolysis.

Glycolysis is a fundamental metabolic pathway occurring in the cytoplasm of cells, present in nearly all living organisms. It’s the initial stage of both aerobic and anaerobic respiration, where glucose is broken down into two molecules of pyruvate.

Here’s a detailed overview:

Preparatory Phase (Energy Investment):

- Glucose Phosphorylation: Glucose is phosphorylated to form glucose-6-phosphate, consuming one ATP molecule in the process.

This step traps glucose within the cell, preventing its diffusion out of the cell.

- Isomerization: Glucose-6-phosphate is converted to fructose-6-phosphate.

- Second Phosphorylation: Fructose-6-phosphate is phosphorylated to form fructose-1,6-bisphosphate, consuming another ATP molecule.

Cleavage Phase (Energy Generation):

- Aldolase Reaction: Fructose-1,6-bisphosphate is cleaved into two three-carbon molecules: dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (G3P).

- Triose Phosphate Isomerase: DHAP is converted into another molecule of G3P, so that both molecules are available for subsequent reactions.

Energy-Conserving Phase:

- Oxidation and Phosphorylation: Each G3P molecule is oxidized, and NAD+ is reduced to NADH. Phosphate groups from inorganic phosphate (Pi) are added to each G3P, forming 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate (1,3-BPG).

- Substrate-level Phosphorylation:

The high-energy phosphate group from 1,3-BPG is transferred to ADP, forming ATP, yielding 3-phosphoglycerate (3-PG).

Pyruvate Formation:

- Phosphoenolpyruvate Formation: Phosphoglycerate mutase and enolase convert 3-PG into 2-phosphoglycerate (2-PG), and then into phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP).

- Substrate-level Phosphorylation: PEP donates its phosphate group to ADP, forming ATP and pyruvate.

Overall, glycolysis results in the net production of 2 molecules of ATP (four are produced, but two were initially consumed) and 2 molecules of NADH per molecule of glucose. The pyruvate produced can enter the citric acid cycle (if oxygen is available) or undergo fermentation in anaerobic conditions to regenerate NAD+ for further glycolysis. Glycolysis plays a crucial role in energy production, providing substrates for various biosynthetic pathways and serving as a control point for regulating cellular metabolism.

(2) What are enzymes and factors affecting enzymatic activity?

Enzymes are biological molecules that act as catalysts, speeding up chemical reactions in living organisms without being consumed in the process. They are typically proteins that facilitate specific biochemical reactions.

Several factors can affect enzymatic activity:

- Temperature: Enzymatic activity is highly temperature-sensitive, with most enzymes exhibiting an optimal temperature at which they function most efficiently. As temperature increases, enzyme activity generally increases due to higher molecular motion and collision rates. However, excessively high temperatures can denature enzymes, causing them to lose their structure and function irreversibly.

- pH: Enzymes have an optimal pH range at which they exhibit maximal activity. Changes in pH outside this range can alter the enzyme’s active site structure and disrupt its ability to bind substrates. pH extremes can denature enzymes or affect the ionization state of amino acid residues critical for catalysis.

- Substrate Concentration: The rate of enzymatic reaction typically increases with increasing substrate concentration until reaching a maximum rate (Vmax). At low substrate concentrations, the enzyme is underutilized and exhibits a linear relationship between substrate concentration and reaction rate. At higher substrate concentrations, the enzyme becomes saturated, and the reaction rate plateaus as all active sites become occupied.

- Enzyme Concentration: The rate of enzymatic reaction is directly proportional to enzyme concentration, assuming substrate concentration is not limiting. Increasing enzyme concentration increases the likelihood of substrate molecules encountering active sites and forming enzyme-substrate complexes, thereby accelerating the reaction rate.

- Cofactors and Coenzymes: Many enzymes require cofactors or coenzymes, such as metal ions or organic molecules, to catalyze reactions effectively. These molecules may bind to the enzyme’s active site or assist in substrate binding, stabilization of reaction intermediates, or transfer of functional groups.

- Inhibitors: Enzyme activity can be inhibited by various molecules, including competitive inhibitors that compete with substrates for binding to the active site, noncompetitive inhibitors that bind to allosteric sites and alter enzyme conformation, and irreversible inhibitors that covalently modify the enzyme. Inhibitors can reduce enzyme activity by blocking substrate binding or interfering with catalytic activity.

- Activators and Modulators: Some molecules, known as activators or modulators, can enhance enzyme activity by binding to specific regulatory sites on the enzyme. These molecules may allosterically enhance enzyme-substrate binding or stabilize the enzyme’s active conformation, leading to increased catalytic activity.

- Enzyme Structure and Conformation: The three-dimensional structure of enzymes is essential for their catalytic function. Changes in enzyme structure due to mutations, denaturation, or environmental factors can affect active site accessibility, substrate binding affinity, and catalytic efficiency.

(3) Explain Urea cycle and its signification.

Urea Cycle

- Formation of Carbamoyl Phosphate: The urea cycle begins in the mitochondria with the formation of carbamoyl phosphate from ammonia, bicarbonate, and ATP. This reaction is catalyzed by the enzyme carbamoyl phosphate synthetase I (CPS I). Ammonia, derived from the breakdown of amino acids, reacts with bicarbonate in the presence of ATP to form carbamoyl phosphate.

- Formation of Citrulline: Carbamoyl phosphate then reacts with ornithine, an amino acid derived from the urea cycle itself, to form citrulline. This reaction is catalyzed by the enzyme ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC), and it occurs in the mitochondrial matrix.

- Formation of Argininosuccinate: Citrulline is transported out of the mitochondria into the cytosol, where it reacts with aspartate to form argininosuccinate. This reaction is catalyzed by the enzyme argininosuccinate synthetase, and it requires ATP.

- Cleavage of Argininosuccinate: Argininosuccinate is then cleaved by the enzyme argininosuccinase, resulting in the release of fumarate and the formation of arginine.

- Formation of Urea: Arginine is hydrolyzed by arginase, releasing urea and regenerating ornithine. Urea is transported to the bloodstream and eventually excreted by the kidneys in the urine, while ornithine returns to the mitochondria to participate in another cycle of the urea cycle.

The significance of the urea cycle lies in several key aspects:

- Ammonia Detoxification: The primary function of the urea cycle is to detoxify ammonia generated from the breakdown of amino acids, the building blocks of proteins. Ammonia is highly toxic to cells, particularly neurons, and can lead to neurological damage and other health complications if not effectively removed from the body.

- Nitrogen Balance: The urea cycle helps maintain nitrogen balance in the body by ensuring that excess nitrogen, derived from dietary protein intake or protein turnover, is efficiently eliminated. Urea synthesis allows the body to excrete excess nitrogen while preserving essential amino acids for protein synthesis and other metabolic processes.

- Energy Production: The urea cycle consumes ATP (adenosine triphosphate) during various enzymatic reactions, providing a mechanism for energy expenditure. The hydrolysis of ATP to ADP and inorganic phosphate drives the conversion of ammonia and bicarbonate ions into urea, contributing to overall energy metabolism.

- Regulation of Acid-Base Balance: By removing excess ammonia, the urea cycle helps regulate acid-base balance in the body. Ammonia can react with water to form ammonium ions, which can contribute to acidosis if not adequately neutralized. Urea synthesis reduces ammonia levels and helps maintain physiological pH levels in tissues and body fluids.

- Clinical Implications: Dysregulation of the urea cycle can lead to various metabolic disorders, collectively known as urea cycle disorders (UCDs). These genetic disorders impair the function of enzymes involved in the urea cycle, resulting in the accumulation of toxic ammonia in the bloodstream. UCDs can manifest with symptoms such as neurological impairment, developmental delays, seizures, and coma, highlighting the critical importance of the urea cycle in maintaining metabolic homeostasis.

2 SHORT NOTES: (ANY THREE) 3×5=15

(1) How carbohydrates can be classified?

Carbohydrates, also known as saccharides or sugars, are organic compounds composed of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen atoms. They are classified based on their chemical structure, size, and complexity. The main types of carbohydrates include:

- Monosaccharides: Monosaccharides are the simplest form of carbohydrates, consisting of single sugar molecules. They cannot be further hydrolyzed into smaller carbohydrates. Examples of monosaccharides include glucose, fructose, and galactose. Monosaccharides are the building blocks of more complex carbohydrates.

- Disaccharides: Disaccharides are composed of two monosaccharide units joined together by a glycosidic bond. They are formed through a condensation reaction (dehydration synthesis) between two monosaccharides, resulting in the elimination of a water molecule. Common disaccharides include sucrose (glucose + fructose), lactose (glucose + galactose), and maltose (glucose + glucose).

- Oligosaccharides: Oligosaccharides consist of 3 to 10 monosaccharide units linked together by glycosidic bonds. They are intermediate in size between disaccharides and polysaccharides. Oligosaccharides are found in various foods and play roles in cell recognition, immune function, and as prebiotics for gut bacteria.

- Polysaccharides: Polysaccharides are complex carbohydrates composed of long chains of monosaccharide units. They can consist of hundreds to thousands of monosaccharide residues linked together by glycosidic bonds. Polysaccharides serve as energy storage molecules (e.g., starch and glycogen) and structural components in cells and tissues (e.g., cellulose and chitin).

Based on their function and structure, carbohydrates can also be classified into two main categories:

- Simple Carbohydrates: Simple carbohydrates include monosaccharides and disaccharides, which are quickly digested and absorbed by the body, leading to rapid spikes in blood sugar levels. Foods rich in simple carbohydrates include fruits, honey, table sugar, and sugary beverages.

- Complex Carbohydrates: Complex carbohydrates include oligosaccharides and polysaccharides, which consist of longer chains of sugar molecules and take longer to digest. They provide sustained energy release and are often rich in dietary fiber, vitamins, and minerals. Foods rich in complex carbohydrates include whole grains, legumes, vegetables, and starchy foods like potatoes and rice.

Overall, carbohydrates play essential roles in providing energy, supporting cellular function, and serving as structural components in living organisms. Their classification helps to understand their diverse functions and dietary implications for human health.

(2) Explain secondary structure of the protein.

The secondary structure of a protein refers to the local spatial arrangement of amino acid residues within a polypeptide chain. It is primarily stabilized by hydrogen bonds between the backbone atoms of amino acids. The two most common types of secondary structure in proteins are alpha helices and beta sheets.

Alpha Helix:

- In an alpha helix, the polypeptide chain adopts a helical structure, resembling a coiled spring. This structure is stabilized by hydrogen bonds formed between the carbonyl oxygen of one amino acid residue and the amide hydrogen of an amino acid located four residues away along the polypeptide chain. This regular hydrogen bonding pattern causes the backbone to twist into a helical shape.

- The alpha helix is characterized by its right-handed coil, with 3.6 amino acid residues per turn of the helix and a rise of 1.5 angstroms per residue along the helical axis. The side chains of the amino acids project outward from the helix axis.

- Alpha helices are commonly found in proteins’ structural regions, such as in the interior of globular proteins or spanning across biological membranes as transmembrane domains. They are also frequently observed in DNA-binding proteins, where they can interact with the major groove of DNA.

Beta Sheet:

- In a beta sheet, the polypeptide chain adopts an extended, zigzag conformation, with adjacent strands lying side-by-side and forming hydrogen bonds between their backbone atoms. Beta sheets can be either parallel or antiparallel, depending on the directionality of the polypeptide strands.

- In a parallel beta sheet, adjacent strands run in the same direction, while in an antiparallel beta sheet, adjacent strands run in opposite directions. The hydrogen bonds in a parallel beta sheet are slightly weaker than those in an antiparallel beta sheet.

- Beta sheets are commonly found in proteins’ structural regions, where they contribute to the stability and rigidity of the protein’s overall fold. They often form the core of protein structures known as beta barrels and are frequently involved in protein-protein interactions and ligand binding.

The secondary structure of a protein, including alpha helices and beta sheets, plays a crucial role in determining its overall three-dimensional structure and function. These regular folding patterns provide stability to the protein and facilitate specific interactions with other molecules, such as substrates, cofactors, and other proteins, essential for biological processes.

(3) What are the mechanism of membrane transport system?

Membrane transport systems are essential for the movement of molecules across biological membranes, facilitating the exchange of ions, nutrients, signaling molecules, and waste products between cells and their environment. There are several mechanisms by which molecules can traverse cell membranes, including passive diffusion, facilitated diffusion, active transport, and vesicular transport. Here’s an overview of each mechanism:

Passive Diffusion:

- Passive diffusion, also known as simple diffusion, is a process by which molecules move across the membrane down their concentration gradient, from an area of higher concentration to an area of lower concentration. This movement occurs spontaneously and does not require energy input from the cell.

- Small, uncharged molecules such as oxygen, carbon dioxide, and lipid-soluble molecules can diffuse freely through the lipid bilayer of the membrane. The rate of diffusion is influenced by factors such as the concentration gradient, membrane permeability, molecular size, and solubility in lipid.

Facilitated Diffusion:

- Facilitated diffusion involves the movement of molecules across the membrane with the assistance of membrane proteins, such as channels or carriers. Unlike passive diffusion, facilitated diffusion allows molecules to move down their concentration gradient but requires specific transport proteins to facilitate their passage.

- Channel proteins form aqueous pores across the membrane, allowing specific ions or small polar molecules to pass through. Carrier proteins bind to the molecule being transported and undergo conformational changes to transport the molecule across the membrane.

- Facilitated diffusion does not require energy input from the cell but is limited by the number of available transport proteins and the rate at which they can facilitate transport.

Active Transport:

- Active transport is a process by which molecules are transported across the membrane against their concentration gradient, from an area of lower concentration to an area of higher concentration. This process requires the input of energy, typically in the form of ATP, to drive the transport against the gradient.

- Carrier proteins known as pumps mediate active transport by undergoing conformational changes powered by ATP hydrolysis. These pumps actively transport ions or molecules, such as sodium, potassium, calcium, and certain nutrients, against their electrochemical gradient.

- Active transport mechanisms play crucial roles in maintaining cellular ion concentrations, generating membrane potential, and transporting nutrients into cells. Examples include the sodium-potassium pump and the calcium pump in plasma membranes and organelle membranes.

Vesicular Transport:

- Vesicular transport involves the movement of large molecules, macromolecules, and particles across membranes via membrane-bound vesicles. This process includes endocytosis, in which materials are taken into the cell, and exocytosis, in which materials are released from the cell.

- Endocytosis encompasses various mechanisms such as phagocytosis (cellular eating), pinocytosis (cellular drinking), and receptor-mediated endocytosis (specific uptake of ligands via receptor-ligand interactions).

- Exocytosis involves the fusion of vesicles with the plasma membrane, releasing their contents into the extracellular space. This process is essential for the secretion of hormones, neurotransmitters, enzymes, and other cellular products.

These mechanisms of membrane transport ensure the dynamic exchange of molecules between cells and their environment, maintaining cellular homeostasis and supporting essential physiological processes in organisms.

(4) What is glucose tolerance test (GTT) ?

A glucose tolerance test is a diagnostic test used to measure how your body’s cells are able to absorb glucose (sugar) from the bloodstream after you consume a specific amount of glucose solution.

It’s commonly used to diagnose diabetes and other blood sugar disorders.

Typically, you’ll fast overnight, then drink a sugary solution. Blood samples are taken at intervals over a few hours to measure how your body processes the sugar.

detailed overview of a glucose tolerance test (GTT):

- Preparation: Before the test, your healthcare provider will provide you with specific instructions. These often include fasting for at least 8 hours prior to the test, which usually means not eating or drinking anything except water.

- Baseline Blood Sample: At the beginning of the test, a baseline blood sample is taken to measure your fasting blood sugar level. This provides a starting point for comparison throughout the test.

- Glucose Solution: After the baseline blood sample is taken, you’ll be given a glucose solution to drink. The solution typically contains a specific amount of glucose dissolved in water. The amount may vary depending on the specific protocol used by your healthcare provider.

- Waiting Period: After consuming the glucose solution, you’ll need to remain at the testing facility for a specified period of time, usually several hours. During this time, you should avoid eating, drinking, or engaging in strenuous physical activity.

- Blood Samples: At regular intervals (usually every 30 minutes to 1 hour), blood samples will be taken from a vein in your arm. These samples are used to measure your blood sugar levels at various points after consuming the glucose solution.

- Monitoring: Throughout the test, your healthcare provider will monitor your symptoms and any changes in your blood sugar levels. It’s important to report any symptoms such as dizziness, lightheadedness, sweating, or nausea.

- Completion: Once the required number of blood samples have been taken and analyzed, the test is complete. Your healthcare provider will review the results and discuss them with you. Depending on the findings, further testing or treatment may be recommended.

The glucose tolerance test is commonly used to diagnose diabetes, gestational diabetes (diabetes during pregnancy), and other disorders related to blood sugar metabolism. It provides valuable information about how your body responds to glucose and can help guide treatment decisions.

(5) What are lipoproteins and their functions?

definition

Lipoproteins are complex particles composed of lipids (fats) and proteins.

They play crucial roles in transporting lipids, such as cholesterol and triglycerides, through the bloodstream.

There are several types of lipoproteins, each with distinct functions:

- Chylomicrons:

These are the largest and least dense lipoproteins. They transport dietary triglycerides and cholesterol from the intestines to the liver and other tissues. - Very Low-Density Lipoproteins (VLDL): VLDL particles are produced by the liver and contain mostly triglycerides. They transport triglycerides to various tissues for energy or storage. As VLDL particles release triglycerides, they become smaller and denser.

- Intermediate-Density Lipoproteins (IDL): IDL particles are formed from the metabolism of VLDL. They contain a mix of triglycerides and cholesterol. IDL particles can be taken up by the liver or further metabolized into low-density lipoproteins (LDL).

- Low-Density Lipoproteins (LDL): LDL particles are often referred to as “bad cholesterol.” They primarily transport cholesterol from the liver to tissues throughout the body. High levels of LDL cholesterol are associated with an increased risk of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease.

- High-Density Lipoproteins (HDL): HDL particles are often referred to as “good cholesterol.” They transport excess cholesterol from tissues back to the liver for excretion or recycling. High levels of HDL cholesterol are associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease.

Functions of lipoproteins include:

- Transporting lipids: Lipoproteins transport lipids, such as cholesterol and triglycerides, through the bloodstream to various tissues in the body.

- Regulating lipid metabolism: Lipoproteins play a role in regulating the metabolism of lipids, including cholesterol synthesis and breakdown.

- Maintaining cell structure and function: Lipids transported by lipoproteins are essential for the structure and function of cell membranes.

- Providing energy: Triglycerides transported by lipoproteins can be used by cells as a source of energy.

- Modulating immune responses: Lipoproteins can interact with components of the immune system and modulate immune responses.

3 SHORT NOTES: (ANY ONE) 3×1=3

(1) What are saturated and unsaturated fatty acids?

Saturated and unsaturated fatty acids are types of fatty acids classified based on their chemical structure:

Saturated Fatty Acids:

- Saturated fatty acids have no double bonds between carbon atoms in their hydrocarbon chain.

- They are “saturated” with hydrogen atoms, meaning each carbon atom in the chain is bonded to the maximum number of hydrogen atoms.

- Saturated fats are typically solid at room temperature.

- They are commonly found in animal products such as meat, butter, cheese, and full-fat dairy products, as well as some plant oils like coconut oil and palm oil.

Unsaturated Fatty Acids:

- Unsaturated fatty acids have one or more double bonds between carbon atoms in their hydrocarbon chain.

- They are “unsaturated” because they can accommodate additional hydrogen atoms.

- Unsaturated fats are typically liquid at room temperature.

- There are two main types of unsaturated fatty acids:

- Monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA): These have one double bond in their hydrocarbon chain. They are found in foods such as olive oil, avocados, nuts, and seeds.

- Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA): These have two or more double bonds in their hydrocarbon chain. They are found in foods such as fatty fish (e.g., salmon, mackerel), flaxseeds, walnuts, and vegetable oils (e.g., soybean oil, sunflower oil).

- Unsaturated fats, particularly those rich in omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids, are considered heart-healthy when consumed in moderation. They can help lower LDL cholesterol levels and reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease.

(2) Give classification and nomenclature of enzymes.

Enzymes are proteins that catalyze biochemical reactions in living organisms, facilitating the conversion of substrates into products. They are classified based on several criteria, including the type of reaction they catalyze, their substrate specificity, and their functional groups. Enzymes are typically named systematically according to the recommendations of the International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (IUBMB). Here’s an overview of the classification and nomenclature of enzymes:

Classification Based on Reaction Type:

- Oxidoreductases: Catalyze oxidation-reduction reactions by transferring electrons between substrates. Examples include dehydrogenases, oxidases, and peroxidases.

- Transferases: Catalyze the transfer of functional groups, such as methyl, acyl, or phosphate groups, between substrates. Examples include kinases, transaminases, and methyltransferases.

- Hydrolases: Catalyze hydrolysis reactions, breaking down substrates by adding water molecules. Examples include proteases, lipases, and glycosidases.

- Lyases: Catalyze the removal or addition of functional groups to substrates without hydrolysis or redox reactions. Examples include decarboxylases, synthases, and aldolases.

- Isomerases: Catalyze the rearrangement of atoms within a molecule to form isomeric products. Examples include isomerases, mutases, and racemases.

- Ligases: Catalyze the joining of two molecules, typically with the consumption of ATP or another high-energy compound. Examples include synthetases and ligases.

Classification Based on Enzyme Commission (EC) Number:

- Enzymes are assigned a unique Enzyme Commission (EC) number based on the type of reaction they catalyze. The EC number consists of a four-digit code, with each digit representing a different aspect of enzyme function:

- The first digit indicates the general class of the enzyme (e.g., oxidoreductases are assigned the number 1).

- The second digit further specifies the subclass of the enzyme.

- The third digit identifies the subclass within the group.

- The fourth digit distinguishes between individual enzymes within the subclass.

- For example, the enzyme lactate dehydrogenase is classified as EC 1.1.1.27, where “1” represents oxidoreductases, “1” indicates alcohol dehydrogenases, “1” specifies L-lactate dehydrogenases, and “27” distinguishes lactate dehydrogenase from other enzymes in the same subclass.

Nomenclature:

- Enzymes are typically named according to the type of reaction they catalyze, followed by the substrate(s) or product(s) involved. The names often end with the suffix “-ase” to indicate their enzymatic nature.

- Enzyme names may also include additional information, such as the source organism, subcellular location, or cofactor dependence. For example, lactate dehydrogenase catalyzes the conversion of lactate to pyruvate, while cytochrome c oxidase catalyzes the oxidation of cytochrome c by molecular oxygen.

Overall, the classification and nomenclature of enzymes provide a systematic framework for organizing and categorizing these essential biological catalysts based on their biochemical properties and functions.

SECTION – II (Biophysics) (37 Marks)

1 LONG ESSAY: (ANY ONE OUT OF TWO) 1×10-10

(1) Define pressure. Enlist various type of pressure in the body. Describe measurement of various type of pressure in body.

Define Pressure :-

Pressure is a measure of the force applied perpendicular to the surface of an object per unit area. It is a scalar quantity and is expressed in units of force divided by area, such as pascals (Pa), atmospheres (atm), pounds per square inch (psi), or torr.

In physics, pressure is defined as:

Pressure=ForceAreaPressure=AreaForce

Where:

- Pressure is the force exerted perpendicular to the surface of an object.

- Force is the magnitude of the force applied perpendicular to the surface.

- Area is the surface area over which the force is distributed

Various Types of body Pressure

- Blood Pressure: The force exerted by circulating blood on the walls of blood vessels. It is typically measured in millimeters of mercury (mmHg) and consists of two values: systolic pressure (the pressure when the heart beats) and diastolic pressure (the pressure when the heart is at rest between beats).

- Intraocular Pressure: The pressure within the eye. Elevated intraocular pressure can be a risk factor for glaucoma.

- Intracranial Pressure: The pressure inside the skull. It can be affected by conditions such as head trauma, brain tumors, or bleeding within the brain.

- Tissue Pressure: The pressure within tissues, which can be influenced by factors such as inflammation, injury, or fluid accumulation.

- Intra-abdominal Pressure:

- Pulmonary Pressure:

- Blood Pressure Measurement: This is typically done using a sphygmomanometer, which consists of an inflatable cuff wrapped around the upper arm and a pressure gauge. The cuff is inflated to a pressure higher than the systolic blood pressure, then slowly deflated while listening for sounds of blood flow with a stethoscope (auscultation) or using automated devices.

- Intraocular Pressure Measurement: This is commonly measured using a tonometer. There are several methods for measuring intraocular pressure, including applanation tonometry and non-contact tonometry.

- Intracranial Pressure Measurement: Direct measurement of intracranial pressure can be done using invasive techniques such as inserting a catheter into the brain or non-invasive methods such as transcranial Doppler ultrasound.

- Tissue Pressure Measurement: Techniques for measuring tissue pressure vary depending on the specific tissue being examined and the clinical context. Examples include using pressure sensors or probes inserted directly into tissues.

Intra-abdominal Pressure Measurement:

- Intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) can be measured using various techniques, including direct and indirect methods.

- Direct methods involve inserting a catheter or sensor directly into the abdominal cavity to measure pressure. This can be achieved surgically or percutaneously using minimally invasive techniques.

- Indirect methods involve using a device such as a urinary bladder catheter or a gastric pressure sensor to estimate IAP based on the pressure transmitted through the intra-abdominal contents.

Pulmonary Pressure Measurement:

- Pulmonary arterial pressure can be measured using a pulmonary artery catheter (Swan-Ganz catheter), which is inserted into the pulmonary artery through a central venous access site.

- The catheter contains pressure sensors that measure pulmonary arterial pressure, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP), and other hemodynamic parameters.

- Non-invasive methods, such as echocardiography and Doppler ultrasound, can also provide indirect assessments of pulmonary pressure by measuring parameters such as tricuspid regurgitant jet velocity and right ventricular systolic pressure.

(2) Define body mechanism. List out principles of body mechanism. Describe maintenance of body mechanism.

Body mechanism” refers to the complex systems and processes within the human body that enable it to function properly. This includes processes such as digestion, circulation, respiration, and nervous system function.

The main principles of body mechanism include:

- Homeostasis: The body’s ability to maintain a stable internal environment despite external changes.

- Feedback mechanisms: Processes that regulate body functions by monitoring changes and adjusting accordingly, such as negative feedback loops that help maintain balance.

- Cellular communication: Cells communicate with each other through various signaling pathways to coordinate functions and responses.

- Energy balance: The body must balance energy intake and expenditure to sustain life and maintain optimal function.

- Structural integrity: The body’s structure, including bones, muscles, and connective tissues, supports movement and protects internal organs.

Maintenance of body mechanism involves various practices and behaviors to support overall health and function:

- Proper nutrition: Eating a balanced diet with essential nutrients supports the body’s energy needs and cellular function.

- Regular exercise: Physical activity helps maintain muscle strength, cardiovascular health, and overall mobility.

- Sufficient rest: Adequate sleep allows the body to repair tissues, consolidate memories, and regulate hormones.

- Hydration: Drinking enough water is essential for bodily functions such as digestion, circulation, and temperature regulation.

- Stress management: Chronic stress can disrupt body mechanisms, so practicing relaxation techniques and stress-reducing activities is important.

- Medical care: Regular check-ups and prompt treatment of any health issues help ensure optimal function and prevent complications.

- Avoidance of harmful substances: Limiting exposure to toxins such as tobacco, alcohol, and environmental pollutants helps protect cellular function and overall health.

2 WRITE SHORT NOTES ON FOLLOWING: 3×5=15

(ANY THREE OUT OF FIVE)

(1) Radio therapy

short note : Radio Therapy

👉Radiotherapy, also known as radiation therapy.

👉It is a medical treatment that uses high-energy radiation to kill cancer cells and shrink tumors.

👉 It works by damaging the DNA inside the cancer cells, preventing them from multiplying and spreading.

👉Radiotherapy can be delivered👉 externally, where a machine directs radiation beams at the cancerous area from outside the body, or internally, where radioactive materials are placed inside the body near the cacancer.

Radiotherapy offers several advantages as a cancer treatment:

- Targeted Treatment: Radiotherapy can be precisely targeted to the tumor site, minimizing damage to surrounding healthy tissues.

- Non-Invasive: Unlike surgery, radiotherapy is a non-invasive treatment, meaning it does not require incisions or anesthesia.

- Versatility: Radiotherapy can be used as a primary treatment, adjuvant therapy (after surgery), or palliative care (to relieve symptoms and improve quality of life).

- Effectiveness: It is effective in killing cancer cells and shrinking tumors, leading to improved outcomes for many cancer patients.

- Combined with Other Treatments: Radiotherapy can be combined with surgery, chemotherapy, or immunotherapy to increase treatment efficacy.

- Customizable Treatment Plans: Treatment plans can be customized based on the type and stage of cancer, as well as the patient’s overall health and treatment goals.

- Outpatient Procedure: In many cases, radiotherapy can be administered on an outpatient basis, allowing patients to continue with their daily activities.

- Pain Relief: Radiotherapy can provide effective pain relief for cancer-related symptoms, such as bone pain or nerve compression.

(2) Defibrillation

Defibrillation is a critical intervention in the management of cardiac arrest and can significantly increase the chances of survival when administered promptly and correctly.

Definition.

Defibrillation is a medical procedure used to restore normal heart rhythm in individuals experiencing life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias, particularly ventricular fibrillation and pulseless ventricular tachycardia.

- Purpose: Defibrillation aims to reset the heart’s electrical activity, allowing it to resume a normal rhythm.

- Equipment: A defibrillator delivers an electrical shock to the heart.

There are different types:

- Manual defibrillators: Operated by healthcare professionals. They require training to use effectively.

- Automated external defibrillators (AEDs): Designed for public use. They provide voice prompts to guide users through the process.

Procedure:

- Assessment: Assess the patient’s condition to confirm cardiac arrest.

- Prepare the patient: Ensure they are lying flat on a firm surface.

- Apply electrodes: Electrodes are placed on the chest in specific locations. These electrodes detect the heart’s electrical activity and deliver the shock.

- Charge the defibrillator: The device is charged to the appropriate energy level.

- Shock delivery: Once charged, the operator delivers the shock by pressing a button. This momentarily stops the heart’s electrical activity, allowing the heart’s natural pacemaker to reestablish a normal rhythm.

Safety:

Before delivering a shock, it’s crucial to ensure no one is touching the patient or the surrounding area to prevent injury.

- Post-defibrillation care: After delivering a shock, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) may be continued to support circulation until the heart resumes beating effectively.

- Monitoring: Continuous monitoring of the patient’s heart rhythm is essential after defibrillation to ensure the return of a sustainable rhythm. Additional shocks may be needed if the arrhythmia persists.

- Follow-up:

Patients who receive defibrillation often require further medical evaluation and treatment to address the underlying cause of the cardiac arrest and to prevent recurrence.

(3) Gravitational forces in context of human body.

Gravitational forces play a crucial role in the context of the human body.

They are responsible for maintaining posture, facilitating movement, and regulating blood flow.

For instance, gravitational forces pull the body downward, which is countered by skeletal and muscular systems to maintain an upright posture.

Additionally, gravity influences blood circulation by aiding the return of blood to the heart from lower extremities. Moreover, gravitational forces also affect bone density, as weight-bearing activities stimulate bone growth and strength.

more detail about gravitational forces in the context of the human body:

- Posture and Alignment: Gravity constantly pulls the body downward, and the musculoskeletal system works to counteract this force to maintain an upright posture.

- Balance and Coordination: Gravity influences the body’s center of mass, which is important for balance and coordination. The vestibular system, located in the inner ear, helps detect changes in orientation and gravity, contributing to balance and spatial awareness.

- Movement and Mobility: Gravity affects movement patterns and mobility.

- Cardiovascular Function: Gravity assists in venous return, the process of blood flowing back to the heart from the extremities.

- Bone Health: Gravity is essential for maintaining bone density and strength. Weight-bearing activities, such as walking, running, and resistance training, stimulate bone remodeling and growth. When bones experience gravitational forces during weight-bearing activities, they adapt by becoming stronger and denser, which helps prevent osteoporosis and bone fractures.

- Respiration: Gravity affects the respiratory system by influencing lung expansion and contraction. .

- Pressure Distribution: Gravity contributes to pressure distribution within the body.

(4) Discuss about temperature scale

Temperature scales are systems for quantifying how hot or cold an object or environment is.

The most commonly used temperature scales are Celsius (°C), Fahrenheit (°F), and Kelvin (K).

Celsius (°C):

- Developed by Swedish astronomer Anders Celsius in 1742.

- The Celsius scale defines 0°C as the freezing point of water and 100°C as the boiling point of water, both at sea level atmospheric pressure.

- Widely used in most of the world for everyday temperature measurements.

- It is based on dividing the temperature range between the freezing and boiling points of water into 100 equal parts.

Fahrenheit (°F):

- Created by German physicist Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit in 1724.

- Initially, he defined 0°F as the lowest temperature he could achieve with a mixture of ice and salt, and 100°F as normal human body temperature.

- Later, he revised the scale, setting 32°F as the freezing point of water and 212°F as the boiling point of water, both at sea level atmospheric pressure.

- Commonly used in the United States and a few other countries, as well as for certain specialized applications.

Kelvin (K):

- Named after Scottish physicist William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin, who proposed the scale in the mid-19th century.

- Kelvin is based on the absolute zero, the theoretical lowest possible temperature where particles have minimal motion. Absolute zero is defined as 0 Kelvin.

- The size of one Kelvin degree is the same as one Celsius degree. The only difference is the starting point, with 0 K being equivalent to -273.15°C.

- Kelvin is commonly used in scientific applications, especially in physics and chemistry, where precise measurements and calculations are required. It is the primary temperature scale used in thermodynamics.

Comparison:

- Celsius and Kelvin scales are related by a simple linear equation (K = °C + 273.15), making conversions between them straightforward.

- Fahrenheit and Celsius scales are related by the equation (°F = (°C × 9/5) + 32).

(5) Use of Light in therapy

Light therapy, also known as phototherapy, involves exposure to specific wavelengths of light to treat various conditions. Here are some common uses of light therapy:

- Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD): Light therapy is often used to treat SAD, a type of depression that occurs at a certain time of year, usually in the fall or winter when daylight hours are shorter. Exposure to bright light, typically from a special light box, can help alleviate symptoms.

- Sleep Disorders: Light therapy can help regulate sleep patterns and treat conditions like insomnia and circadian rhythm disorders. Exposure to bright light in the morning can help reset the body’s internal clock and improve sleep quality.

- Skin Conditions: Certain skin conditions, such as psoriasis, eczema, and acne, can benefit from light therapy. Different wavelengths of light can target specific skin issues, either by reducing inflammation, killing bacteria, or promoting skin healing.

- Pain Management: Light therapy has been used to alleviate pain associated with conditions such as arthritis, fibromyalgia, and muscle soreness. Near-infrared light therapy, in particular, is believed to penetrate deeper into tissues and promote healing.

- Mood Disorders: In addition to SAD, light therapy may also be used to treat other mood disorders such as depression and anxiety. Exposure to bright light can trigger the release of neurotransmitters like serotonin, which can improve mood and overall well-being.

- Jet Lag: Light therapy can help alleviate symptoms of jet lag by adjusting the body’s internal clock to a new time zone. Exposure to light at specific times can help synchronize the body’s circadian rhythm with the local time.

Overall, light therapy offers a non-invasive and relatively safe treatment option for a variety of conditions, although it’s essential to use it under the guidance of a healthcare professional, as improper use can lead to adverse effects.

3 VERY SHORT ANSWER : (NO CHOICE) 6×2-12

(1) Sterilization

Sterilization refers to the process of completely removing or destroying all forms of microbial life, including bacteria, viruses, and spores, from an object or a surface.

It’s commonly used in medical and laboratory settings to prevent the spread of infections and ensure the safety of equipment and materials.

There are various methods of sterilization, including:

- Autoclaving

- Ethylene oxide (ETO) sterilization

- Radiation sterilization

- Dry heat sterilization

- Chemical sterilization

(2) ECG

definition

ECG stands for electrocardiogram.

It’s a medical test that records the electrical activity of the heart over a period of time using electrodes placed on the skin.

ECGs are used to diagnose various heart conditions, including arrhythmias,

heart attacks, and other heart abnormalities.

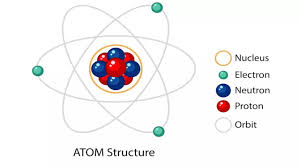

(3) Structure of Atom

The structure of an atom consists of a nucleus containing protons and neutrons, surrounded by electrons orbiting the nucleus in various energy levels or shells.

Protons have a positive charge, neutrons have no charge, and electrons have a negative charge.

The number of protons determines the element’s identity, while the number of electrons balances the positive charge of the protons to make the atom electrically neutral.

The arrangement of electrons in the shells follows specific rules, such as the Aufbau principle, Pauli exclusion principle, and Hund’s rule.

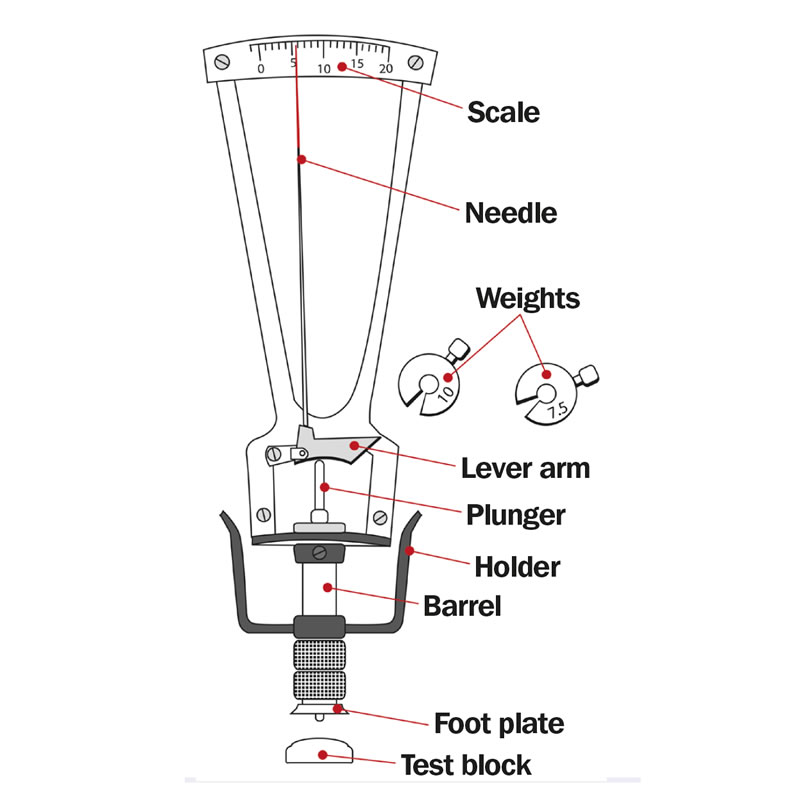

(4) Tonometry

onometry is the measurement of intraocular pressure (IOP) within the eye.

It’s an essential test in diagnosing and managing conditions like glaucoma, where increased intraocular pressure can damage the optic nerve and lead to vision loss.

One common method of tonometry involves using a device called a tonometer to gently touch the surface of the eye or measure the pressure without touching the eye directly.

Another method involves a puff of air directed at the eye to measure the cornea’s resistance, known as non-contact tonometry.

Tonometry helps eye care professionals monitor eye health and adjust treatment plans as needed.

(5) Humidity

Humidity refers to the amount of water vapor present in the air.

It’s a crucial factor in weather and climate, as well as indoor comfort and health.

Humidity levels can affect how comfortable we feel, as well as how certain materials behave.

High humidity can make the air feel muggy and uncomfortable, while low humidity can lead to dry skin,respiratory issues, and static electricity.

Humidity is typically measured as relative humidity, which expresses the amount of water vapor present in the air as a percentage of the maximum amount the air can hold at a given temperature.

(6) Types of Scans.

There are various types of scans used in different fields for imaging and diagnosis.

Some common types include:

- X-ray: Uses electromagnetic radiation to create images of the inside of the body,

- CT scan (Computed Tomography): Combines X-rays with computer technology to produce cross-sectional images of the body, useful for diagnosing conditions in organs, bones, and soft tissues.

- MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging): Utilizes powerful magnets and radio waves to create detailed images of organs, tissues, and structures within the body, particularly useful for soft tissue and neurological imaging.

- Ultrasound: Uses sound waves to create images of internal organs and structures, commonly used in obstetrics, cardiology, and abdominal imaging.

- PET scan (Positron Emission Tomography): Involves injecting a radioactive tracer into the body to detect changes in cellular activity, often used in cancer diagnosis and staging.

- Bone scan: Involves injecting a radioactive tracer into the bloodstream to detect areas of increased or decreased bone metabolism, helpful in diagnosing bone conditions like fractures, infection, or cancer.

- Mammogram: A specialized X-ray of the breast tissue used for breast cancer screening and diagnosis.